Sarah Koten immigrated to the United States in 1902. Five years later, she began working under the tutelage of Dr. Martin W. Auspitz, who ran a sanitarium where Koten was also allowed to live. According to the June 9, 1908, issue of the New York Times, Koten worked with Auspitz for about five months. “I was frightened and did not want to stay,” she later told a coroner, “but the doctor wanted me to stay, and said he would make a trained nurse out of me.” Then one morning, as she told it, Auspitz chloroformed and raped her in the room where she slept at the sanitarium.

Koten found herself pregnant. According to Koten, Auspitz pressured her to get an abortion, but she refused and left the job.

Finding herself poor and unable to obtain work due to her pregnancy, Koten, an unmarried Russian Jewish immigrant, went to the courts and brought suit against Dr. Auspitz for the rape and to hold him responsible for the unborn child. He denied the accusations, and defense-witness testimony from Auspitz’s brother and brother-in-law maligned Koten’s character. The presiding judge acquitted the doctor on the grounds of insufficient evidence. Turned away by the police, and advised by the district attorney that she had no other legal recourse for what the doctor had done to her, Koten sought redress on her own terms. She lured Auspitz to a made-up patient’s home and, upon his arrival, shot and killed him.

Koten gave birth to her child during the year she spent imprisoned while on trial. Then Koten became a lightning rod for the early feminist angst against the injustices of American workplaces of the day, a hero to female labor leaders, and a dark inspiration to other women who would go on to murder men and cite Koten as a role model.

Rachel Elin Nolan, a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Connecticut, analyzes Koten’s story in a recent article in the feminist journal Signs. Nolan’s article traces the evolution of the press’s coverage of Koten “as a ‘wretched’ and ‘frenzied’ girl and ‘a total wreck’ ” into an object of public sympathy. According to Nolan, when Koten was first arraigned, the press “delighted in recounting anecdotes about her ostensible hysteria and criminality.” However, as the story evolved, Auspitz’s history of being accused of sexual violence against women emerged. Two women had previously come forward to name him as their attacker, with one going so far as to try to kill him herself. (According to the Washington Post, Hannah Jensen, a patient of Auspitz’s at the saniatrium, attempted to shoot him but was less successful than Koten. She was arrested but allowed to go free as long as she promised not to harm him.)

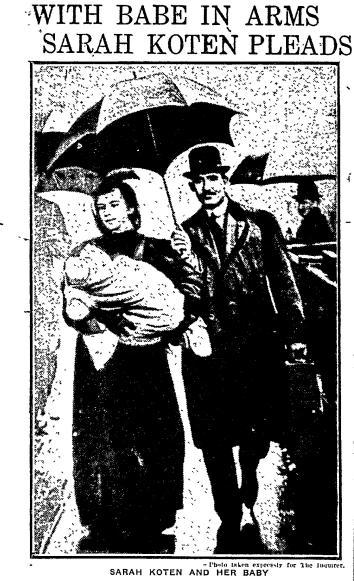

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Aided by the public’s temporary interest in broader patterns of male abuses against women and Koten’s insistence that her attack of Auspitz was done to save other women from him, the press started to turn in Koten’s favor. While the trial was ongoing, the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader quoted Koten as sublimating her own needs to her son’s: “There is nothing in the world like loving as a mother loves. I think of nothing but him. It makes no difference what comes to me, I am not anything myself … I have no care for anything but the baby.” In their coverage of the trial, the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader and the Philadelphia Inquirer ran pictures of Koten holding her newborn son, Abraham.

Her story was also featured in a suffrage-themed issue of the Coming Nation, then a popular socialist newspaper, as an example of how an ideal immigrant, a “frail little woman,” saw her hopes of prosperity dashed by the workplace exploitation endured by women. By the time the case ended, Koten’s image had been rehabilitated. Mercy was granted to the submissive new mother who had been victimized and forced into poverty when she was unable to obtain justice against her abusive employer through legal pathways.

In an interview with Slate, Nolan explained that Koten’s story was taken at the time as evidence that a “new unwritten law” was emerging. Up until the late 19th century, the unwritten law was a sort of widely shared “ ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ that if another man had meddled with a woman in his life, it was acceptable that he would retaliate.” In the late 19th century, however, the press began discussing a new unwritten law that applied to the women who experienced violence at the hands of men: Because they had little power to stop men’s aggression through other means, they were allowed to commit violence themselves in response.

As Nolan explained, “This often hinged on the women making the claim, ‘I’m just a woman. I couldn’t do anything else but pick up a gun and shoot him.’ ” While this shift in public opinion provided women grounds for justifying retaliation, it was also contingent on their willingness to emphasize not their autonomy but their victimhood. To earn mercy, they had to concede: “I’m so weak; he was so powerful.”

This shift in public perception Koten experienced benefited her legally and served to bolster the political aims of the groups that used her story to further their own causes, but, as Nolan points out, it ultimately obscured her efforts to lay claim to her own autonomy in the face of a system that had failed her. While awaiting trial, Koten was interviewed by well-known socialist activist Rose Pastor Stokes, who would become a strong ally of Koten’s throughout the trial (and would go on to use Koten’s story as the basis for her 1916 play The Woman Who Wouldn’t …).

Koten made clear to Stokes that murdering Dr. Auspitz was not merely a last-ditch effort to spare herself of any future abuses at his hand but a kind of activism on behalf of other poor women: “When I thought of my broken life and the lives he might live to break, well, I felt it was my duty to kill him.” The public sympathy from which Koten ultimately benefited was contingent on her desperate victimhood rather than what she saw herself as: an empowered and righteous avenger.

Nolan notes that, left to their own devices, women seeking retaliation against men who had wronged them began to cite Koten’s case as inspiration for their own violent actions. Later in 1908, Sarah Comiskey tried to kill her father for deserting his family. That same year, Nellie Walden killed her ex-boyfriend for abandoning her, and in early 1909, a woman named Elizabeth threatened a man named Charles Schmidt, telling him that if he didn’t marry her, she would “blow out his brains like Sarah Koten did.” (He complied, but ultimately had the marriage annulled.) Each of these women claimed Koten as inspiration. Yet none was able to convincingly demonstrate her victimhood enough to draw the leniency under Koten had.

Unwritten laws, while potentially powerful, are no substitute for policies or systems. They are subject to varied interpretation, trust, and shared sensibility among their various constituents, to an informal and often inequitable adjudication of who “counts” as a viable complainant. And, most importantly, unwritten laws leave little recourse for victims who are unable to game the implicit codes in their favor and convince the audience they were helpless (white, of course) victims deserving of sympathy and the benefits of the unwritten laws. Of course, it’s men’s belief that nobody will believe the women they assault that often leads them to target them in the first place. This is likely why a doctor back in 1908 thought he could get away with raping a nurse. Koten’s story is only one for the history books because, in this case, he turned out to be wrong.

In many ways, this is the argument anti-rape activists have been making for years about rape culture: How we respond to those who say they have been sexually assaulted and preventing sexual violence in the first place are not unrelated issues. Thanks to the shift in public opinion, the resulting mercy granted by Justice James A. Blanchard, and the help of the women’s organization that took her into its care, Koten was given the chance to retreat into anonymity and “rear her child” in what early-20th-century Pennsylvanian publication the Index called “ignorance of the crime its mother had committed.”

Because Koten likely changed her name, Nolan has spent considerable time trying to find out what became of her and her child to no avail.

Did she go on to live a happy life with her child? How did she pay the bills? Did her next employers mistreat her, or did she get respect and a guarantee of safety while she worked?

When the only kind of justice for workplace abuse comes in the court of public opinion, what kind of peace does it offer the victim in the long run? These are answers Koten’s story can’t give us.