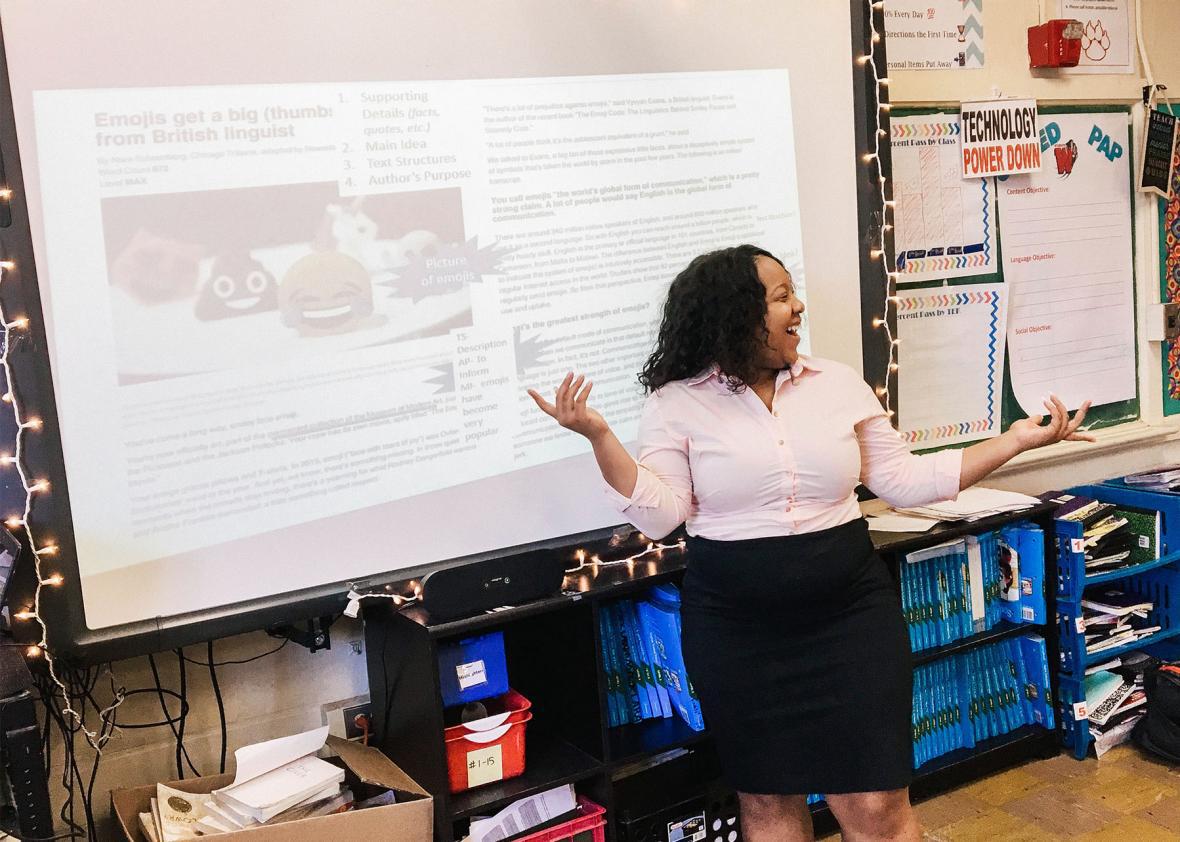

In Eliza Harris’ seventh-grade classroom, one can hardly tell that it resides within the poorest ZIP code in San Antonio, Texas—a city with one of the largest income inequality problems in the country.

A large poster hangs above the whiteboard with the words “Growth Mindset” boldly stamped in silver bubble letters. A cursory glance to the right reveals an aged shelf jam-packed with books—among them, countless volumes of the much-requested tween comedy novel Diary of A Wimpy Kid. And on her desk, there is a predictable assortment of goods: pencils, markers, a pack of Elmer’s glue, a foot-high stack of lined paper.

Like many other teachers across the country, Eliza spends a significant amount of money every year preparing her classroom to meet her students’ needs. In addition to what is visible within the room, she also pays out-of-pocket for afterschool tutoring snacks, instructional materials to compensate for outdated textbooks, and tissues and Lysol wipes to keep widescale contagion at-bay. She estimates that the sum of her yearly personal expenses is a whopping $800.

Eliza Harris

Eliza Harris

When asked why she chooses to personally finance her classroom, Eliza is frank: “I do it because it’s my job. Without essential items like pencils, pens, notebooks, glue, and books, learning wouldn’t happen. It’s my job is to ensure learning happens.” She is not alone; 99 percent of teachers do the same, according to a nationwide Scholastic survey.

The same survey estimated that teachers spend an average of $530 out-of-pocket for classroom supplies per year. Teachers who work in high poverty areas shoulder a larger burden—spending about 40 percent more than their peers in wealthier areas. This comes as no surprise when per-student spending has dropped steadily in the last decade and in some states has slid below the amount spent before the Great Depression.

For their sacrifice, our current tax code allows teachers a $250 deduction. Teachers can deduct this amount from their total earned income for covering necessary materials regardless of whether they itemize their deductions. The fate of teachers like Eliza who take advantage of this tax deduction year after year were recently put on the chopping block in the GOP tax bill.

The tax bill House Republicans passed last month eliminated this small tax break for teachers completely. The Senate version of the bill, by contrast, expanded the teacher tax deduction to $500—an amount more in line with teachers’ real out-of-pocket spending.

When asked how she felt about the potential elimination of the tax break she uses every year, Eliza put her reaction simply: “I’m angry.” We all should be too. That House Republicans chose to include teachers in their ensuing tug-of-war between Senate Republicans reached a new level of moral turpitude.

On Wednesday, House and Senate Republicans reached an agreement a consensus tax bill they hope to send to the president’s desk by next week. The official text of the final bill has not been released yet, but sources have reported Republican lawmakers chose to keep the $250 deduction for teachers.

Such a decision is a small victory for teachers and female teachers especially, who would have borne the greatest negative impact had the tax deduction been scrapped. Currently, women comprise 76 percent of teachers in K-12, and 80 percent in elementary and middle schools. Of female teachers, women of color would have likely been hit the hardest, as they are more likely to work in the most needy and hard-to-staff schools.

But this victory will be short-lived for many teachers who still face a host of other challenges. With an average salary of $58,000 per year, teaching is not paid nearly as well as professions that require similar schooling or professions more populated by men. Moreover, statistics show that teacher wages are actually decreasing, even as cost of living continues to rise. Across all states, teachers earned 1.6 percent less on average in 2015 than they did in 2005, after adjusting for inflation. In some states, the drop was even more pronounced: Illinois teachers made 13.5 percent less in 2015 than they did a decade earlier.

It’s no surprise then, that the nation is facing a serious staffing crisis. In 2017 alone, thousands of positions went unfilled across the country according to a list compiled by the U.S. Education Department. In Arizona, the number of unfilled position was as high as 1 in 5. The profession is also experiencing a high level of attrition, with 8 percent of teachers leaving every year, according to a 2016 Learning Policy Institute report. And our ability to recruit and keep more teacher candidates is severely compromised by efforts to take away already-scarce benefits.

Our task now should be to elevate both the status and compensation of the teaching profession so that we can recruit good teachers that are a critical investment in our country’s future and who are educating the students who need good teachers the most.