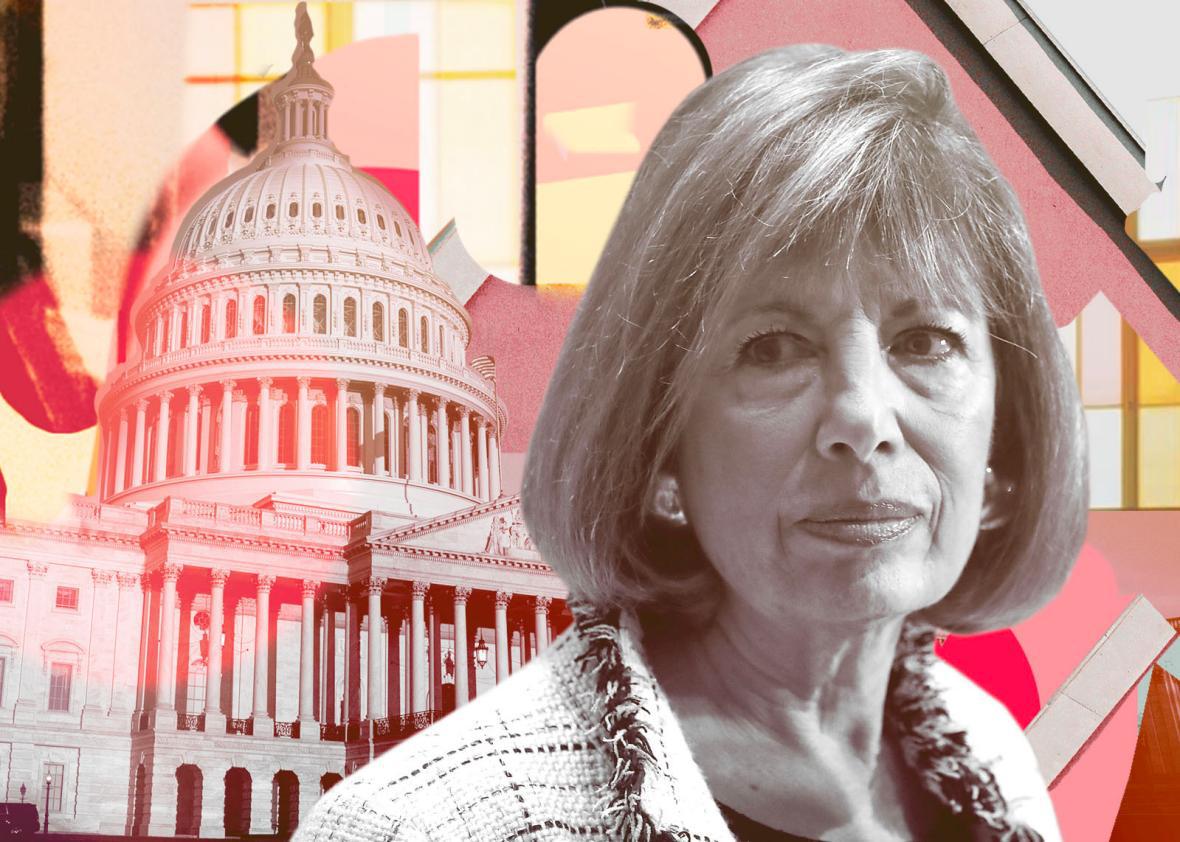

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

As prominent leaders in Hollywood, publishing, and journalism face the immediate effects of sexual harassment allegations coming to light, Congress, too, is having its #MeToo moment, and it is long overdue.

The options for congressional staff to report an allegation as serious as sexual harassment are decidedly insufficient, with Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., who recently came out with her own story of being assaulted as a congressional staffer, describing the process as “constructed to protect the institution—and to impede the victim from getting justice.”

I wrote about this issue with Hannah Hess in 2015. A self-identified 26-year-old man had written on an online message board limited to users physically inside the Capitol complex: “She has slapped my ass, talked about her vibrator, and has asked me sexual questions. I have ignored them but I am thinking about going to the member.” He was talking about his chief of staff and whether he should confide in the member of Congress they both worked for. One user warned him not to take the matter up the chain: “You need to accept that your career on the Hill will be over.”

In lieu of an HR department, staffers have the Office of Compliance, a confidential agency within Congress, tucked away in a far corner, to whom they can report such claims. But many staffers do not even know this option exists, or how to find it. It’s far from where they work and unlike most offices, it’s not required by HR that these resources be posted on company bulletin boards. And many staffers are young, with little previous work experience and a strong desire to not do anything that could damage their career prospects.

Most Hill staff would be more likely to leave their jobs than face the repercussions for making public allegations. Now Rep. Speier is calling for a #MeTooCongress campaign to get other members and staff to speak out about the harassment complaints on Capitol Hill.

The very structure of offices on Capitol Hill makes speaking out about these issues difficult. Each House of Representatives office is structured like a small business with a group of approximately 20 staffers, split between D.C. and their district offices back home. (Senate offices are larger, some with their own office managers to run the HR operations.) A member of congress runs the office, and often has the final say in hiring and firing decisions. Most staffers hope that time spent working in the halls of Congress will yield valuable work experience and connections that will shape their careers for years to come. Despite the relatively low pay that many offices offer, the jobs are competitive, and an office can receive hundreds of résumés for an entry-level position. In this environment, it’s not surprising that people may be reluctant to come forward and risk jeopardizing their professional position.

The infrastructure in place for congressional staff today can be traced back to Newt Gingrich’s contract with America, which ushered in the Congressional Accountability Act, which was considered a spectacular bipartisan legislative feat at the time.

The goal was to hold Congress to the same standards as any other private sector workplace. The bill applied major labor and employment laws to Congress. It allowed congressional support agencies, like the architect of the Capitol, which does much of the maintenance and service for the Capitol complex, and the U.S. Capitol Police to organize unions (though the legislation deliberately prohibited members’ staff and some other congressional employees from doing so).

But members of Congress expressed concerns about staff filing grievances and the potential political fallout. The Office of Compliance was established as a compromise. Its function would be to implement and enforce the CAA, and provide confidential counseling and mediation as the first steps in the grievance process, thus sparing a member of Congress any embarrassment unless a complaint escalated to the highest levels.

Speier has criticized the Office of Compliance counseling system as “toothless,” pointing out that it’s designed to protect lawmakers rather than a harassed staffer. But the OOC has its hands largely tied, with limited resources and limited ability to proactively offer harassment prevention training to Congress (offices that do request such trainings are granted them, but the offices that are mindful enough to request such proactive interventions are likely not usually the ones that need it). There are a number of situations when counseling could be effective, particularly for when interoffice romantic relationships sour and staffers aren’t sure the best course forward. (Open up the New York Times wedding announcements, and you’ll find plenty of examples of Capitol Hill staff getting married to one another, which says nothing of the broken relationships along the way.)

But this system isn’t working for the most serious and sensitive concerns staff might seek to address. Seeking “confidential counseling” with the Office of Compliance is the first step in the formal dispute resolution process. I reported in CQ Roll Call last year that of the more than “2,100 requests for counseling filed with the Office of Compliance since its reporting began in 1996,” the vast majority came from employees not working for Congress.

There are more than three times the number of congressional employees as other support staff served by the OOC (Capitol Police and architect of the Capitol), according to numbers provided by Legistorm, yet only 12 percent of requests for counseling came from employees of the House of Representatives and 5 percent from the Senate. To believe these reports of wrongdoing reflect the reality of what’s actually taking place, we’d have to believe congressional offices are places with scant harassment or hostility. We have plenty of indications to the contrary.

Long before the fallout from the numerous allegations against Harvey Weinstein, the news has fluttered with headlines about members of Congress or senators forced to step down after allegations of sexual harassment come to light: Rep. Mark Foley, R-Fla., stepped down after sexually harassing teenagers who served as Senate pages, Rep. Eric Massa, D-N.Y., resigned after aides reported unwanted sexual advances (remember those awkward “tickle fight” descriptions?). Rep. Mark Souder, R-Ind., and Sen. John Ensign, R-Nev., both resigned after affairs with their staffers surfaced. Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y., resigned and continued collateral damage after his sexual proclivities continued (again and again) to make headlines and take down everyone else around him. Most recently, Rep. Tim Murphy, R-Pa., stepped down after an affair was reported and a chief of staff’s memo was leaked, citing hostile office conditions.

And this is just the list of allegations against members of Congress. It says nothing about the high-ranking aides who could assert their authority in unwanted ways. In Rep. Speier’s now public account of being sexually assaulted when she was a congressional staffer, it was an aide, not a member of Congress, who was her alleged perpetrator.

The low rates of counseling sought have prompted the Office of Compliance to proactively reach out to Hill staff in recent years. “We could do a better job of communicating the rights and responsibilities of what the workplace statute gives staff,” said Alan Friedman, one of the OOC board members and a labor and employment law attorney. “We are working with Congress to do that better through new avenues of communication.”

The combination of these efforts plus the unusual public scrutiny on Congress in general leads some to suggest the standards for workplace conduct in Congress are already high enough. “Congress is covered by a standard if the private standard had to live by they would shun. Congress is more transparent than the private sector and greater accountability to their customers,” said Brad Fitch, president of the Congressional Management Foundation.

He noted the financial disclosures, open information about salaries and spending, and the two-year election cycle of being held accountable to constituents.

Fitch is right, and Congress should be held to high standards. But it doesn’t make the situation any easier for aides caught in the crosshairs: Going public with a boss’s ill behavior can cost him his job, as well as the jobs of all the staffers who work for him, too. Political parties jump at the opportunity to pick up the seat when a member of Congress has resigned in disgrace—witness the current fervor for Democrats to try and pick up Murphy’s once-solidly safe seat after his resignation.

For a staffer working on issues they truly care about, what sort of pause does that give them before speaking out about harassment at work? Beyond getting more uptake of existing counseling it will likely take an entire culture shift—starting with some mandatory sexual harassment trainings—to change business as usual on Capitol Hill.