Yazmin Gil moved to the United States from Mexico when she was 16. Three years later and barely out of high school, Gil was hired as a teacher’s assistant in a Washington state school district where instruction was split between English and Spanish. “I was the native [Spanish] speaker. The teacher was not a native speaker. I was doing the Spanish instruction two days and the next two days she would do the English instruction,” Gil says. Yet she was still earning the salary of a teacher’s aide, also known as a paraprofessional—about half of what certified teachers earn annually.

Gil is now a kindergarten teacher in a dual immersion program, but getting her certification took her eight years at three different schools. The district she worked in as a teacher’s assistant paid for her first semester of college; once that financial support was gone, Gil moved to community college. Later, to accommodate her work schedule, she took classes at night and on weekends. “It was a long journey,” she says.

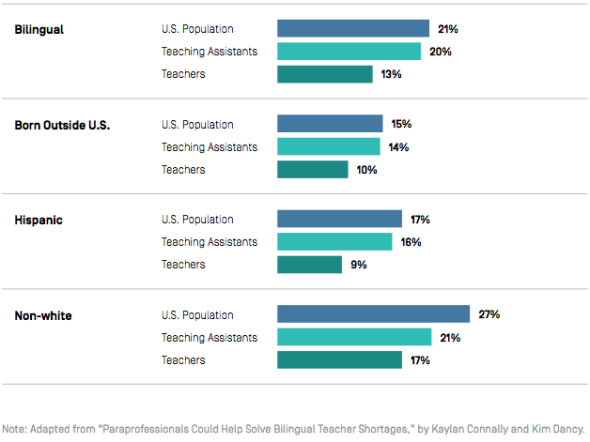

Currently, many states and local school districts need to fill shortages of bilingual, dual immersion, and English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers to meet the needs of their growing English learner student population. Paraprofessionals more closely match the racial and linguistic diversity of the U.S. student population, with about one-fifth of paraprofessionals speaking a non-English language at home and around 20 percent self-identifying as non-White. It is clear that paraprofessionals can help to diversify the mostly white, monolingual K-12 teacher workforce by filling teacher shortages. Yet they often face bureaucratic, linguistic, and financial barriers to entering the teaching profession.

Source: Kaylan Connally, Amaya Garcia, Shayna Cook, and Conor Williams. Teacher Talent Untapped: Multilingual Paraprofessionals Speak About the Barriers to Entering the Profession (Washington, D.C.: New America, January 2017).

In a recent report for New America, we examined these barriers from the perspective of 62 multilingual paraprofessionals in five different U.S. cities. Many reported that it was difficult to attend classes, pay for courses, and manage the complex teacher certification and licensure process while also supporting their families financially and otherwise. Some already had bachelor’s degrees in education from their home countries, but had difficulty getting their credentials translated and accepted for full certification.

The incentives for making the jump from paraprofessional to certified teacher are clear. While elementary teachers’ median salary is $53,760, paraprofessionals’ median pay is $24,900, which approaches the federal poverty line for a family of four—it barely covers the cost of food and housing, much less schooling. Now, some states and districts are addressing these barriers with specialized programs.

This year, Gil is a teacher mentor in her district’s two-year Bilingual Teacher Fellows Program, a partnership between Highline Public Schools and Woodring College of Education at Western Washington University that prepares paraprofessionals to earn their teacher certification. The 17 fellows will earn a bachelor’s degree and K-8 teaching credentials in a program structured to reduce financial, academic, and bureaucratic barriers to success. A mentor teacher gives them ongoing feedback on lesson plans and instruction. Each fellow has a WWU field mentor to help them with problem-solving, and WWU administrative staff are on hand to help fellows navigate the university admission process. And fellows receive $8,000 annual scholarships plus assistance applying for additional financial aid. Growing a pool of bilingual educators is essential to the district’s long-term goal: to have every student graduate bilingual and biliterate by 2026.

A handful of other states and districts have also developed “Grow Your Own” programs to help bring more paraprofessionals to the front of the classroom. South Dakota’s paraprofessional-to-teacher program helps build a pipeline of teachers on Native American reservations who are already invested and engrained in these communities. Many rural schools, often on reservations, face significant teacher shortages, so the state is investing in paraprofessionals to help close this gap. “Given the remote location of most of our tribal communities and most of our schools, it’s really hard to recruit and retain teachers from outside,” says Mato Standing High, director of Indian Education in South Dakota. “The idea is to capture those folks who are already working in the schools, who have good solid experience with the children, a good perspective on what the kids need and what the community and school need.”

Building those connections is also an essential component of Highline’s program. Gil has come full circle and now has the opportunity to coach Letys Ellefson, a WWU fellow on her road to becoming a certified teacher. “I wish I had something like this when I was working as a para,” Gil says, “and really had the support from the teachers I was working with…to [learn] all the little pieces to becoming a teacher.”