David Attie was still a student in his first ever photography course at the New School when he got his big break.

His instructor was Alexey Brodovitch, the famed art director of Harper’s Bazaar, and he’d taken a liking to Attie’s unique photo montages, which Attie created one night in a panic from film he’d accidentally overexposed. Brodovitch asked him to recreate the process to illustrate Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which was to be published for the first time in the magazine.

Attie worked for months to make the images, but the novella didn’t end up running in Harper’s under a directive from Hearst, the magazine’s publisher. Capote resold the novella to Esquire, but when it appeared in the magazine, only one of Attie’s images ran alongside it.

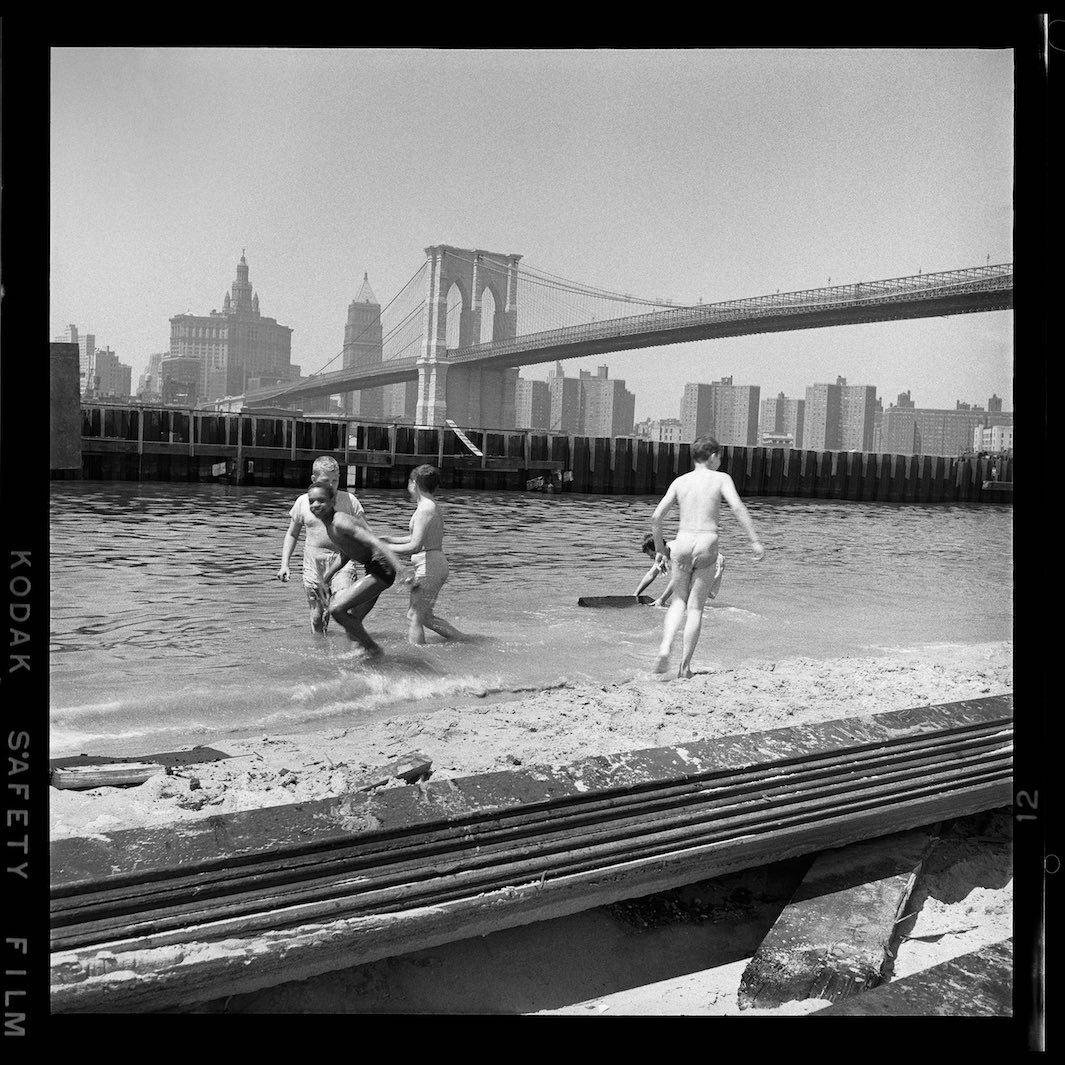

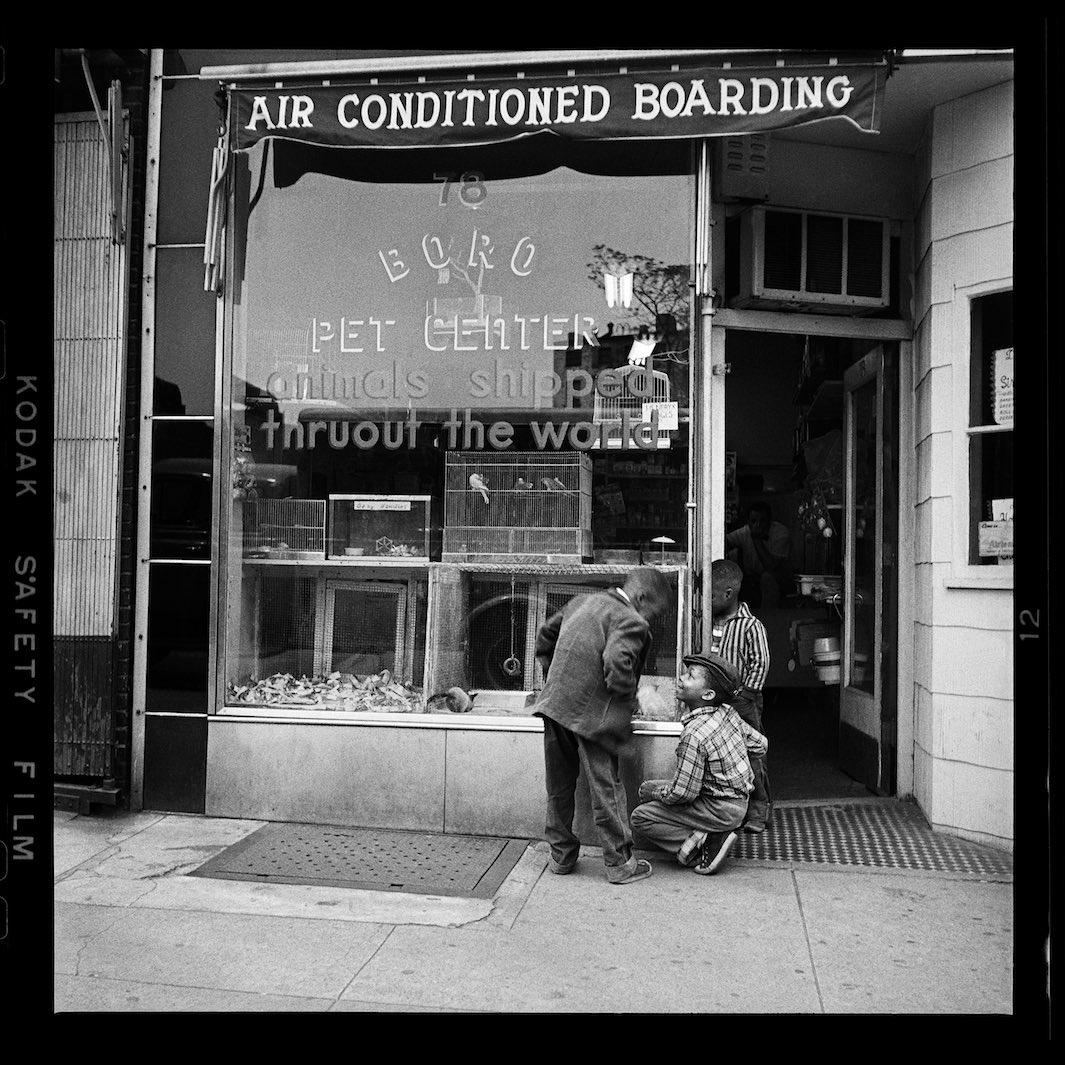

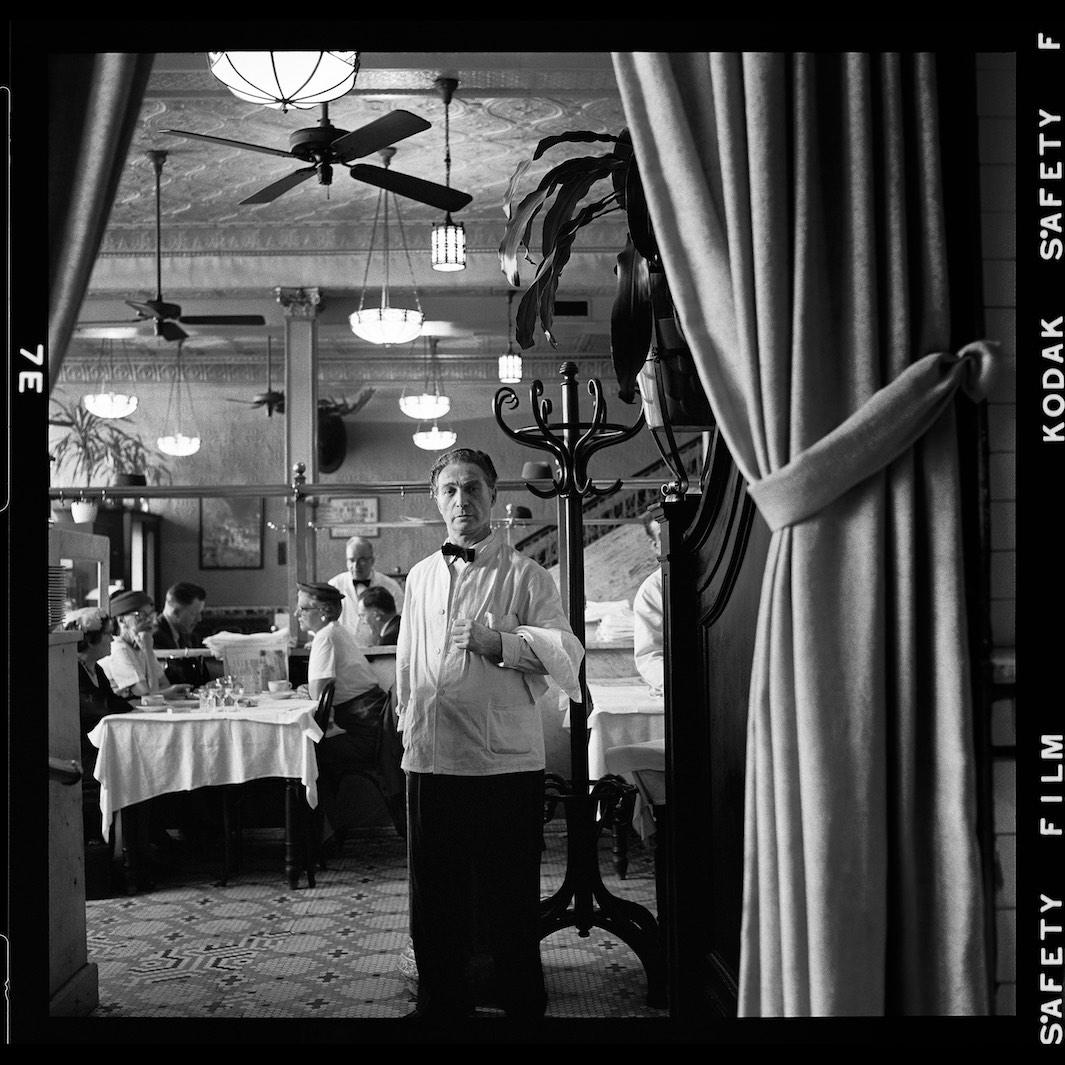

Soon after, when Holiday magazine asked Capote to write an essay, “Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir,” about living in the borough, Attie was again enlisted to provide the accompanying artwork. In March 1958, the young photographer, himself a Brooklyn native, and the young writer spent a day roaming Brooklyn Heights and Dumbo together. Capote posed for Attie and introduced him to some of the people and places he loved. Their work ran in the February 1959 issue of Holiday.

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie

Eli Attie, David’s son, didn’t know about any of this until long after his father died. In 2012, he ran a Google search on his father and discovered that little of his decades of work had been remembered, at least online. Eli, who works as a writer for television, posted a comment on one of the few blogs that mentioned his father. Soon after, Brian Homer, a British photographer, contacted him and offered to help him get David’s work out in the world. The pair, along with Eli’s brother and mother, started looking through boxes of old negatives. On a subsequent trip, Eli found a box labeled “Holiday, Capote, A3/58,” with 800 negatives inside.

“It turned out my mother had known he’d photographed Capote, but she didn’t know a lot about it and hadn’t seen the photos. In my childhood, Capote was a hugely famous person. Maybe that says something about my dad. Maybe he was just a guy who wasn’t impressed with celebrity. If I had photographed the young Truman Capote, I’d probably walk around with sandwich boards proclaiming it on the street,” Eli said.

Last year, a selection of David Attie’s photographs were published by the Little Bookroom in a new edition of Capote’s famous essay, Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir, With the Lost Photos of David Attie. Now, they’re on display at the Brooklyn Historical Society in the exhibition “Truman Capote’s Brooklyn: The Lost Photographs of David Attie” until next July.

“I think he’d be speechless. I think he’d be thrilled,” Eli Attie said. “He was not an unsuccessful photographer. He put out some books. He was on TV once. But I don’t think he ever got this kind of attention.”

“I’m biased. I’m his son. If he took blurry Polaroids that were not framed properly I might think they were great. What’s been incredibly gratifying for me is to see how many people have been touched by his work and have found something special in it,” he added.

Marcia Ely, the Brooklyn Historical Society’s vice president of programs and external affairs, said the photographs succeed, on one level, as a rare glimpse of a literary icon on the brink of fame. But they also serve as a detailed and loving portrait of two neighborhoods at a grittier and less affluent time in the borough’s history, she said.

“As a son of Brooklyn who grew up in Bensonhurst, I think he’d be bowled over by how stylish and hip Brooklyn has become,” Attie said.

As Attie has continued to explore his father’s archives, he said he’s learned a lot more about his life and work. He’s uncovered photos of chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer, the composer Leonard Bernstein, and the actress Jayne Mansfield, among other gems. One day, Attie hopes, those, too, will see the light of day.

“I think there’s 50 books in that archive. It’s a question of finding it and shaping it. It’s so fun for me because it’s a journey into his life and a journey into all these different worlds. I think all of it probably speaks more powerfully now than it did in its time,” he said.

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie

Original print by David Attie