As temperatures skyrocket this summer, heat-related illness isn’t the only threat to public health. Water scarcity is also a major concern. Rainfall gets scant when the mercury runs high, and according to the Washington Post, ascending sea levels in the Middle East are making groundwater too salty to use for drinking or agriculture.

For those living in the Indus River Delta in southeastern Pakistan’s Thatta region, these issues are a daily reality. Water is hard to come by, and many have to spend hours traveling every day to get it from canals connected to Keenjhar Lake. Since the region is near the coast, it’s particularly susceptible to saline intrusion and flooding. In 2010, when devastating floods tore through the country, the Indus Delta was one of the worst affected areas.

For two weeks this February, New York–based photographer Malin Fezehai, on a commission from the H&M Foundation and WaterAid, visited the region to document how water scarcity and climate change affect the lives of the area’s poor and marginalized families. Her photos are featured in the exhibition “Noori Tales: Stories From the Indus Delta,” which is on display at Kungsträdgarden in Stockholm from Monday until Sept. 4.

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

Women and girls doing the washing in a salinated rivulet in Noor Muhammad Thaheem.

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

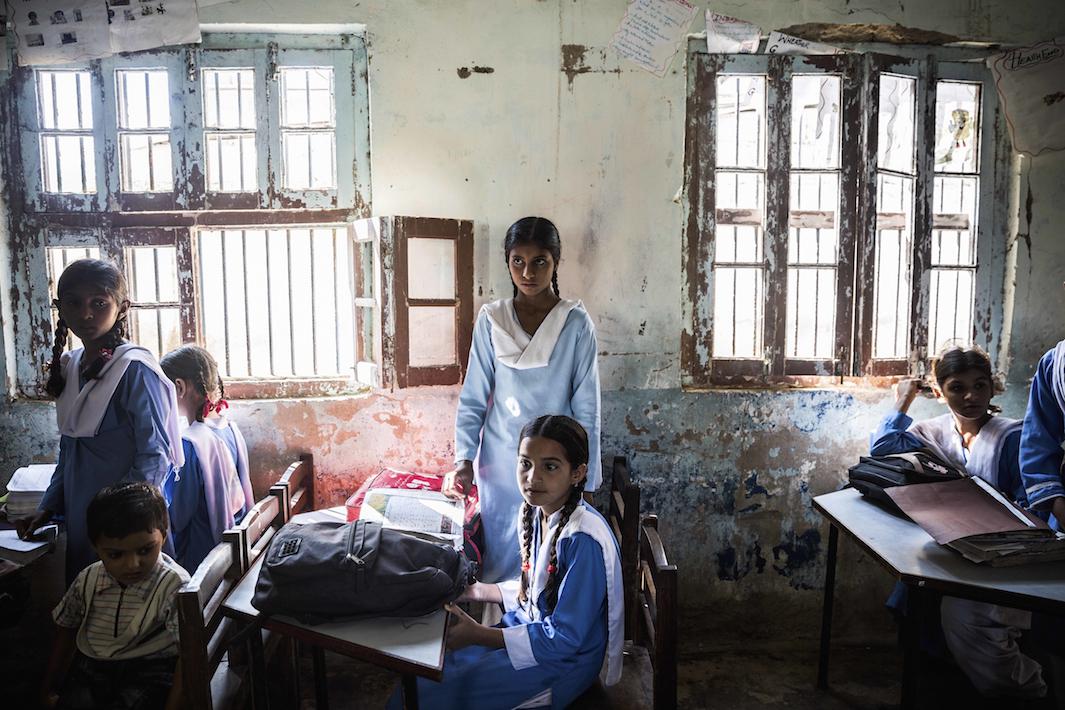

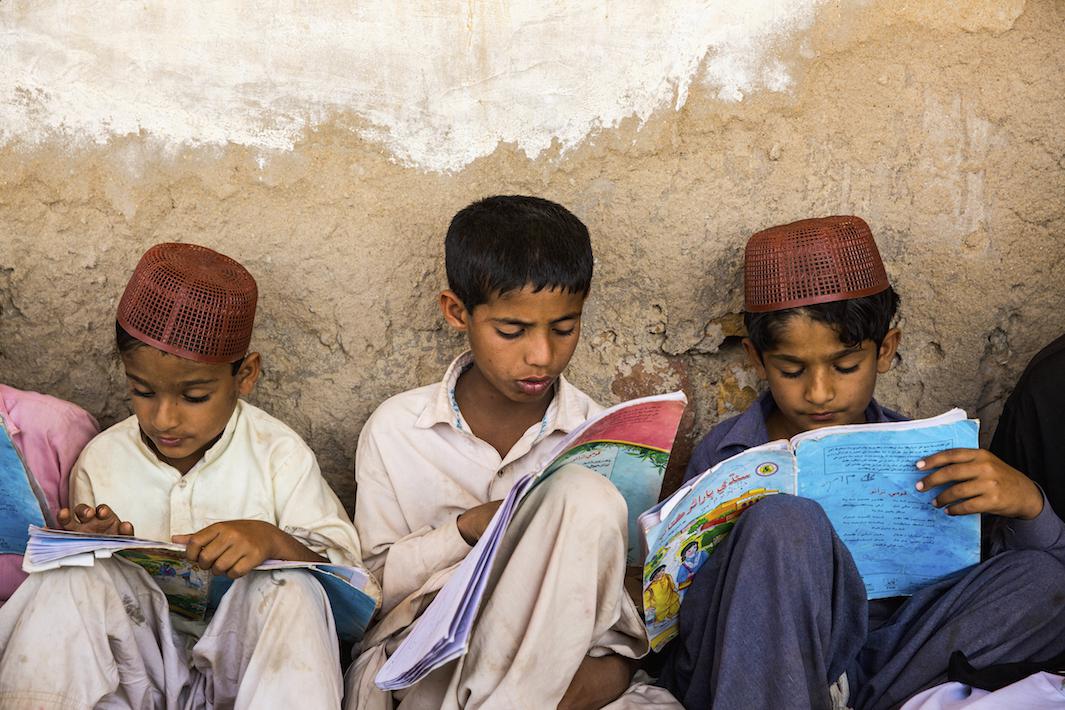

Fezehai’s photos largely focus on the area’s schools, where the H&M Foundation, WaterAid, and National Rural Support Program are building safe drinking water facilities and bathrooms designed to be resistant to flooding and saline erosion. In the past, the absence of these kinds of facilities has kept many students, particularly girls, from staying in school or even enrolling in the first place. Erosion from increasingly salty groundwater, meanwhile, has caused walls and ceilings in some of the schools to collapse.

“The saline intrusion is caused by a combination of factors. It’s barrages on the river upstream, the destruction of mangroves downstream, and it’s both of these being driven by climate change at the global revel,” said Louise Whiting, a policy analyst for water security and climate change at WaterAid.

Fezehai spent her days photographing young students at school and at home across the region. She illustrated how, in areas where the drinking and sanitation facilities had already been built, life was beginning to get slightly easier. In areas where the facilities had not yet been built, her photos underscored the challenges of daily survival and the urgent need for aid. In both cases, her photos show people making do, however they can, with what they have.

“When you talk about water scarcity, you always want to personalize the issue and show what it means for the people on the ground—put faces to the numbers,” Fezehai said.

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid

Malin Fezehai/WaterAid