In Bangkok, as in many parts of the world where cellphones now dominate, phone booths are a dying breed. While thousands have already been removed, many thousands still stand, and they play an evolving—and fascinating—role in the urban landscape. On a visit to Bangkok in 2012, Frank Hallam Day walked by a booth one night and, as he observed headlights from a passing car brighten its glass walls, he was inspired to photograph it. He then started photographing booths all over the city and has continued to do so on annual trips to the city ever since.

“Sometimes I’d see six of them in a row, and then I’d come back two years later and there’d only be one of the six left. A year later, they’d all be gone. So I have a collection of vanished urban furniture in a way,” he said.

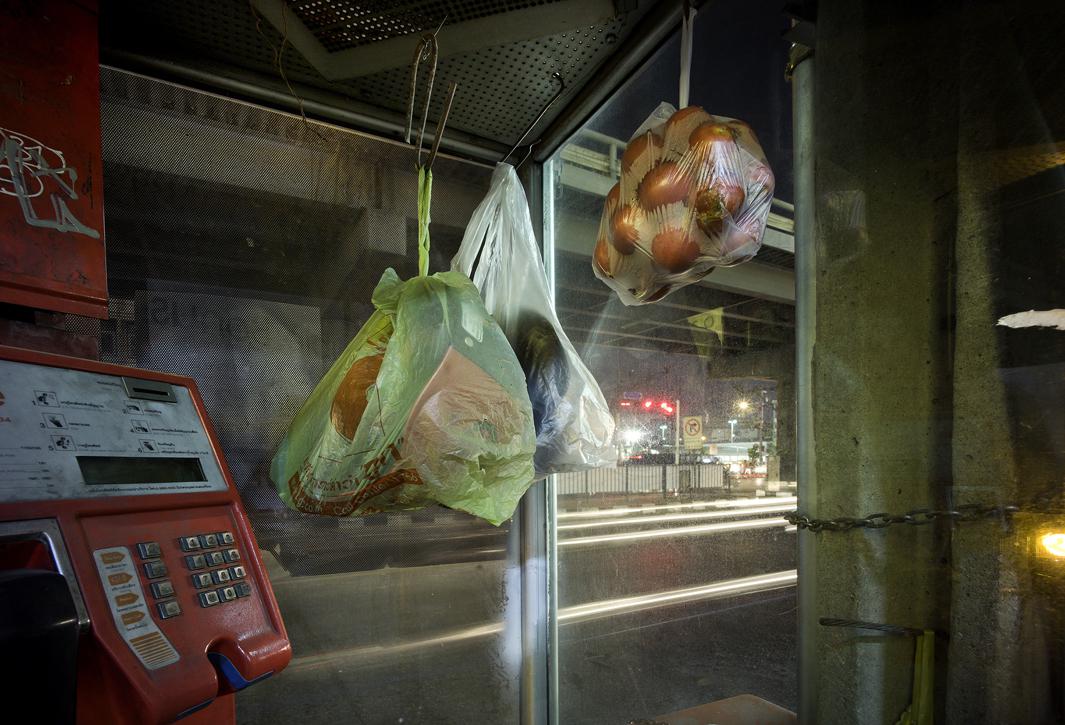

Day shot virtually all of these photos from inside the booths. The spaces were hot and cramped, but he said he often spent as much as an hour in them, waiting for car headlight or a brake light to illuminate the grit, graffiti, and color within the way he wanted. Day sees his photos as still lifes, so he made sure to consider their lighting and composition with the “formality and deliberateness” of a Flemish painter. When everything luminesces just the right way, for a brief moment, he said, the grime can actually look stunning.

“It’s quite an amazing thing, if you take the time to look, and most people, for good reasons I suppose, walk by them and don’t look at them as an artistic subject. But once you do that there’s a lot there,” he said.

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

The booths aren’t just objects of aesthetic interest, Day said; they’re also fascinating sociological phenomena. Though they’re rarely used to make phone calls, he said, street merchants and pedestrians often make them into makeshift storage units. As a result, Day likes to think of them as “little terrariums of urban life.”

“If you make a little hole in an urban space and you put walls and a door around that hole, it gets used. It’s sort of a private space in a very public sphere,” he said.

Most of the time, Day worked in the booths undisturbed. On a few occasions, people interrupted him to retrieve something they’d stored inside. People came in to actually make a call only twice, he said, which underscored why phone booths are disappearing and what that says about how we relate to our inventions.

“They’re symbols of the transitory nature of our relationship with technology. Phone booths existed for 100 years, and in a period of a few years they’ve almost completely disappeared,” he said.

Day’s series, “Call Waiting” is on display at Leica Gallery Los Angeles until Sept. 4.

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day