“The rich have their own photographers,” said the late Milton Rogovin, who devoted his entire career as a documentarian to highlighting the other half—the poor and working classes—with the respect they deserved. He will soon be celebrated at the San Jose Museum of Art in the exhibition “Life and Labor: The Photographs of Milton Rogovin” from Aug. 18 until March 19.

Rogovin was born in New York City in 1909, and a few years after graduating from Columbia University in 1938, he moved to Buffalo, New York, to set up an optometry business. During the Great Depression, as inequality grew starker, he became involved in leftist causes. According to Marja van der Loo, who curated the exhibit, he started reading the Daily Worker and found inspiration in the social documentary photographs of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine. He bought his first camera in 1942 but took photographs only casually for more than a decade.

This changed when his politics led him to be called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1957. The local newspaper proclaimed him the city’s predominant “Red,” so people in his community were afraid to associate with him and his family. His business suffered. He was resilient, however, so the next year he started concentrating on making photos that would express his view of the world and create social change. His first project was a study of storefront churches on Buffalo’s East Side.

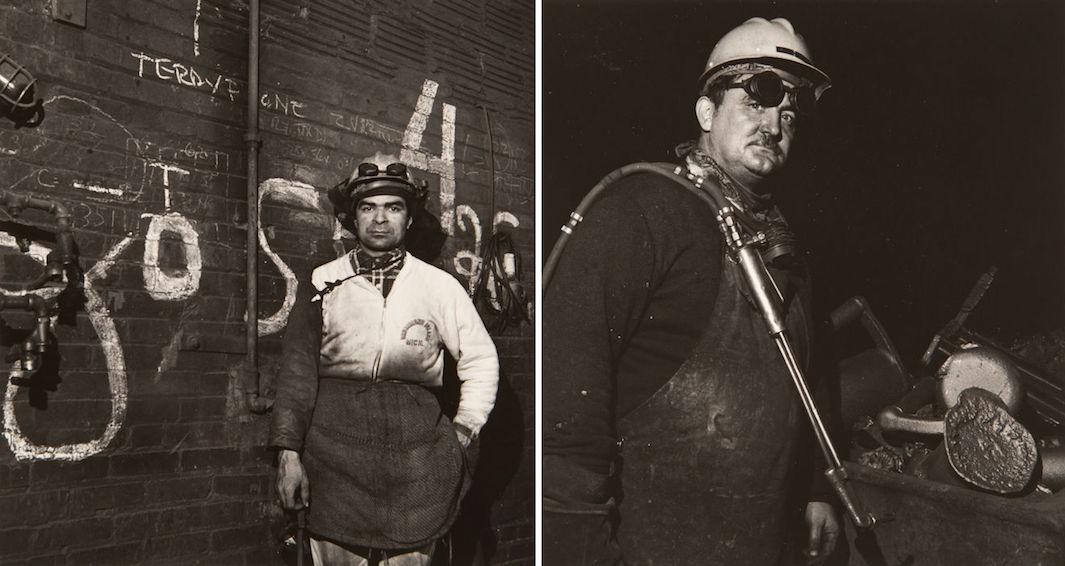

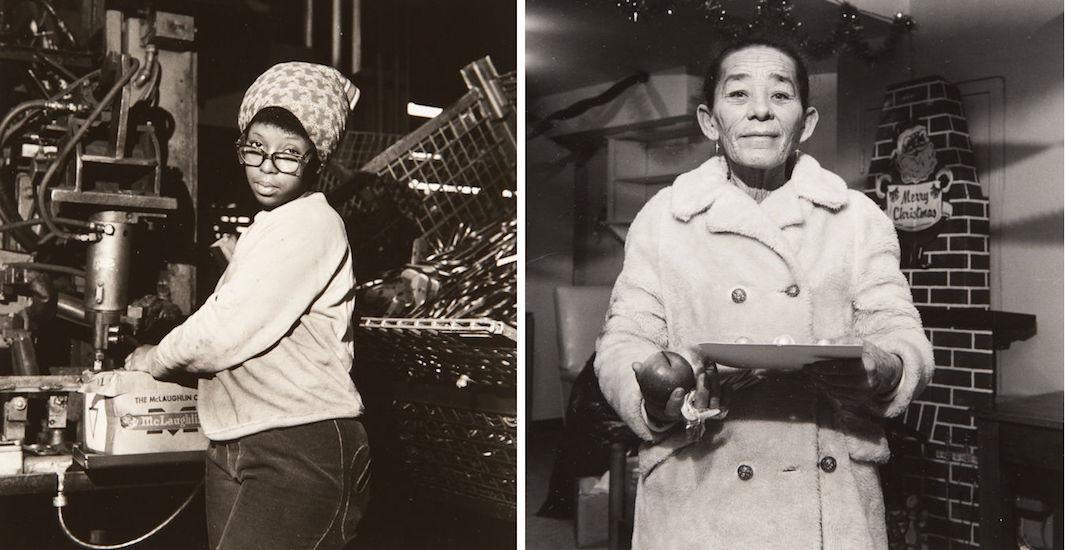

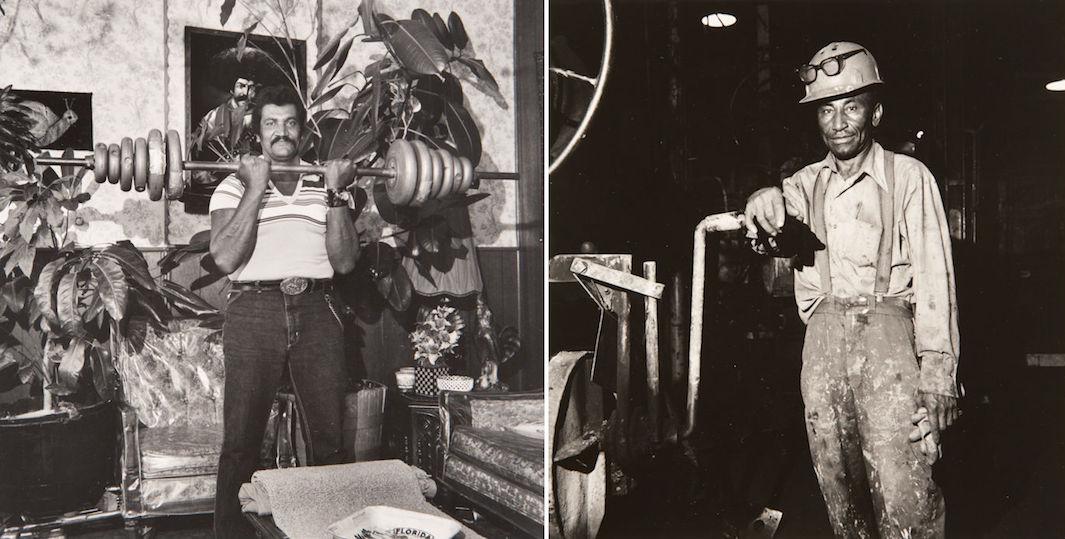

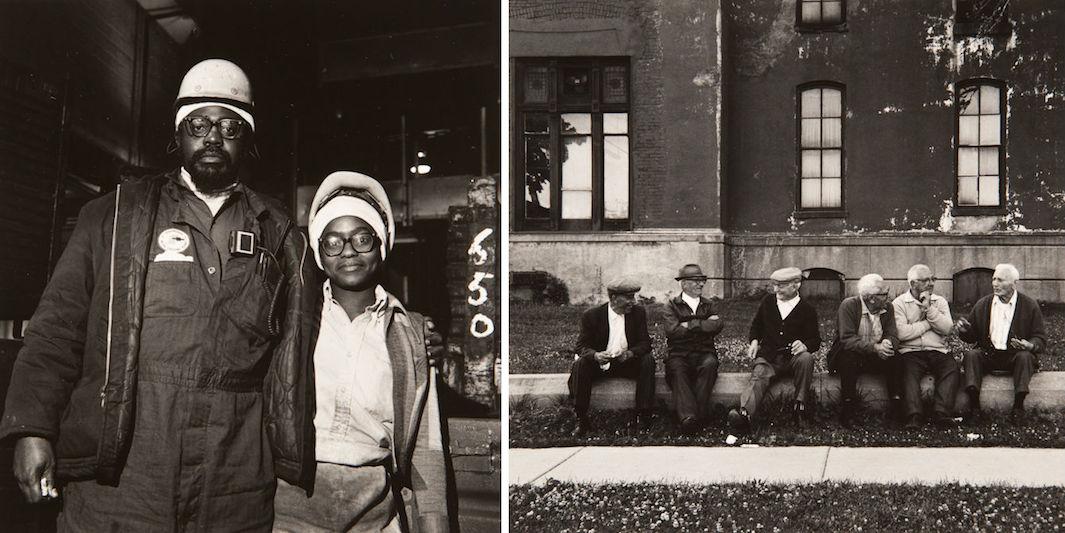

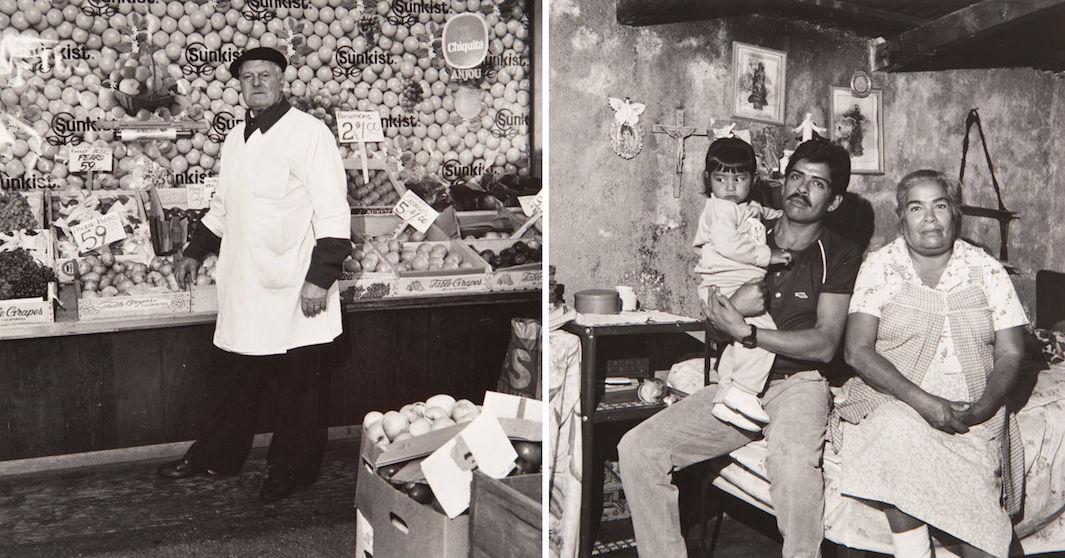

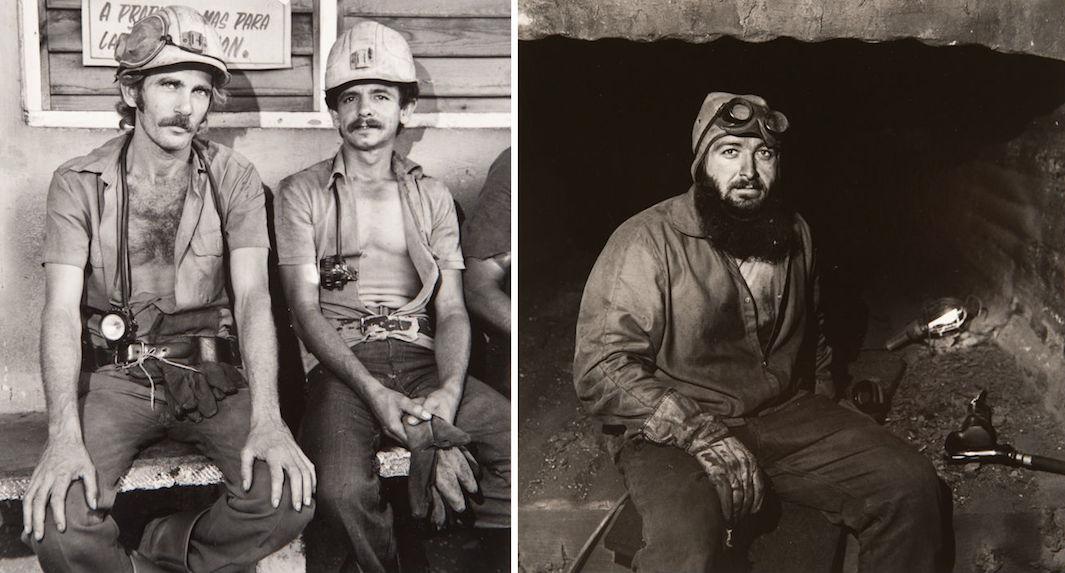

The three series represented in the exhibit focus on people at home and at work. “Working People” documents the decline of Buffalo’s steel industry and other working-class people. “Family of Miners” shows miners and their families around the world. And “Lower West Side, Buffalo,” celebrates a neighborhood of poor- and working-class people near Rogovin’s business. He described his subjects as “the forgotten ones.”

Milton Rogovin. Collection of San Jose Museum of Art.

Milton Rogovin. Collection of San Jose Museum of Art.

Milton Rogovin. Collection of San Jose Museum of Art.

Rogovin’s photos are carefully composed and present people in spaces and occupations that make them feel proud. Both his subject matter, and the way he presented it, was rare at the time.

“Today, we don’t think about anything not being photographed because photography is so ubiquitous. But not so long ago people weren’t necessarily concentrating on these things,” van der Loo said.

Later in life, after he closed his business, Rogovin was able to focus on photography full time. His wife, Anne Snetsky, who was a teacher, author, and activist, often accompanied him and helped him connect with subjects. He continued worked into his 90s and died just after his 101st birthday in 2011.

“What he left behind is a passionate and friendly historical snapshot of a time and a place and people that easily could have been forgotten or overlooked,” said van der Loo.

Milton Rogovin. Collection of San Jose Museum of Art.

Milton Rogovin. Collection of San Jose Museum of Art.