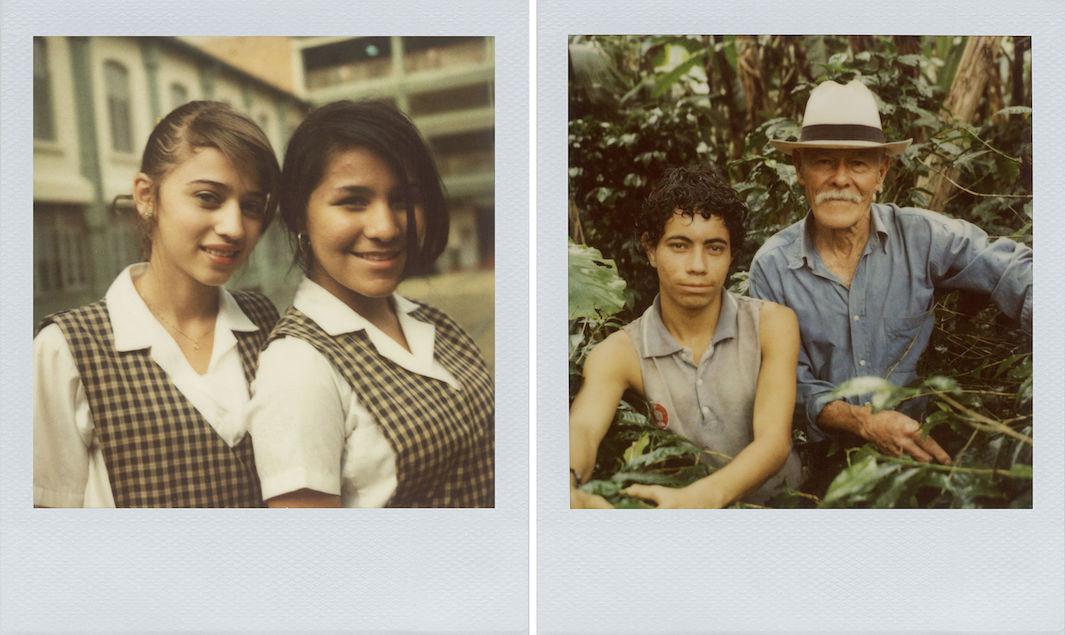

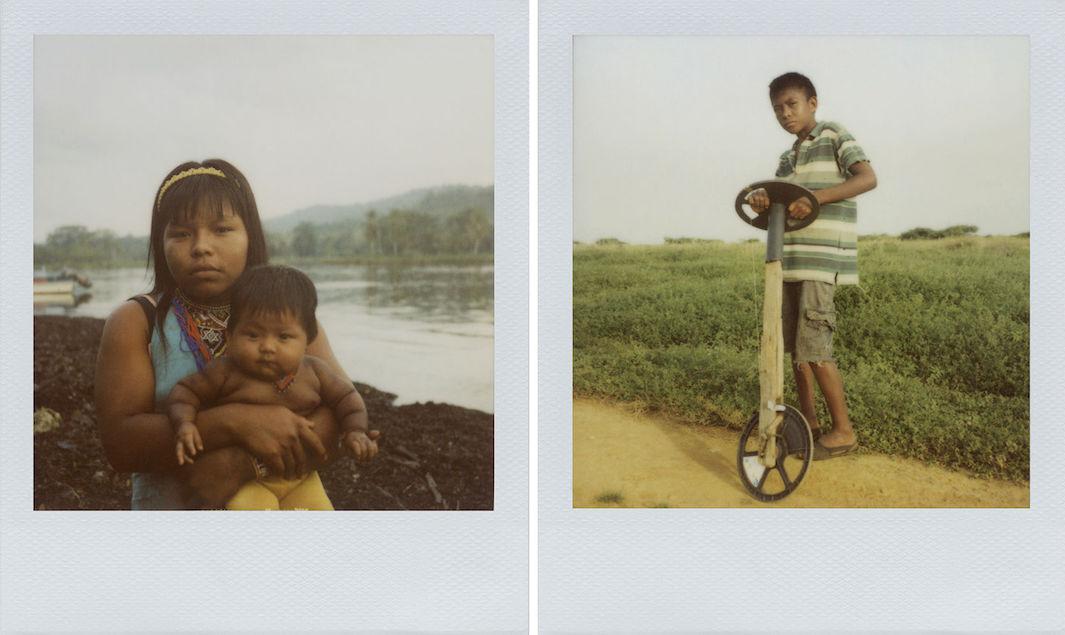

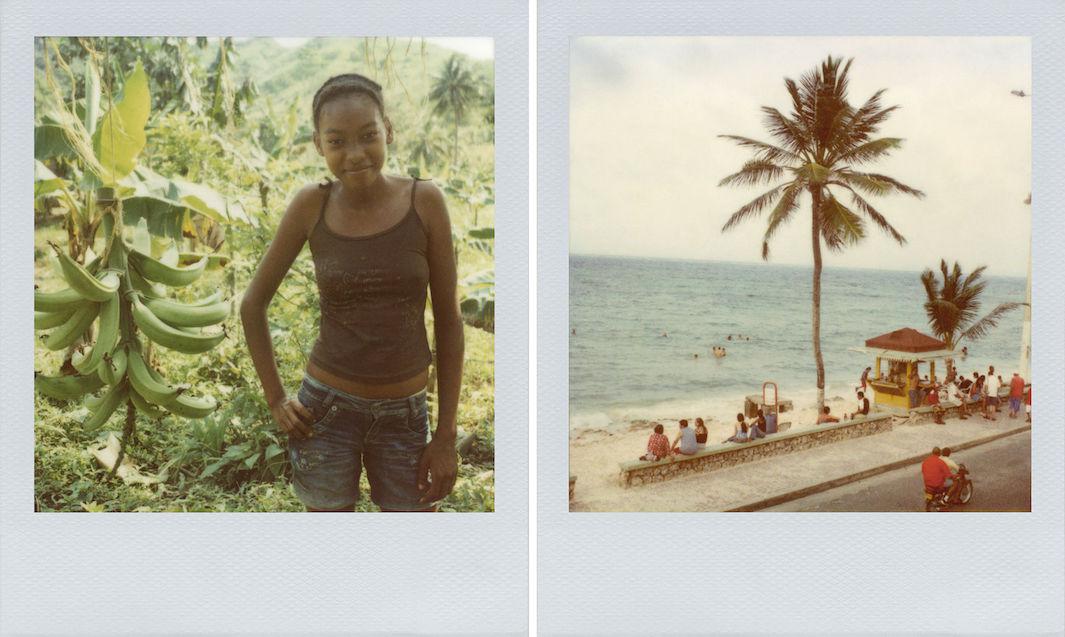

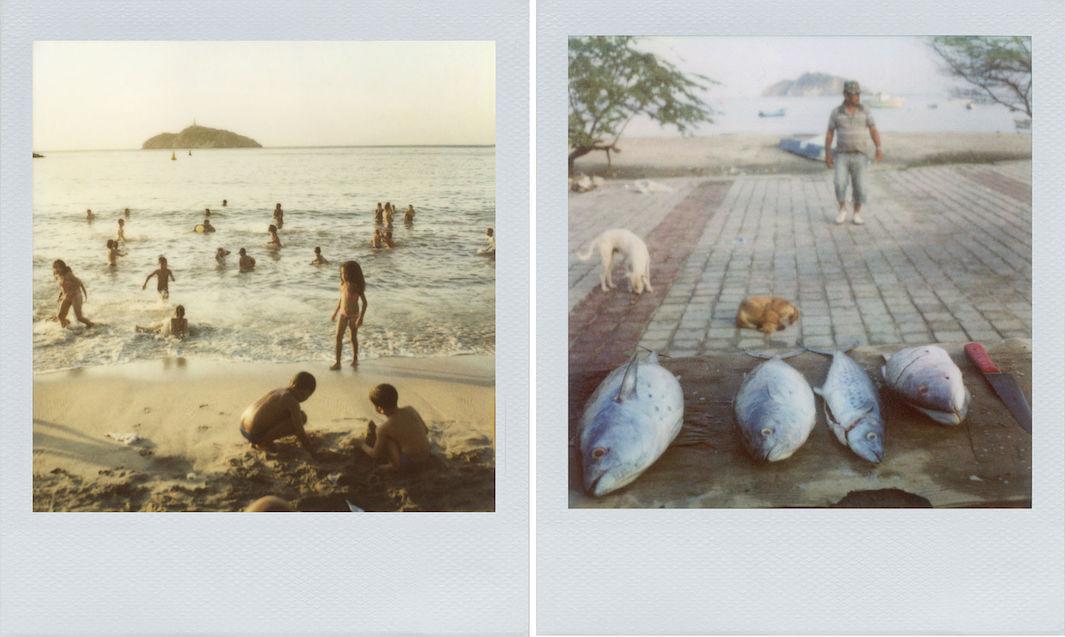

When Colombia makes international headlines, the news—drug trafficking, violence, crime—often isn’t great. But since his first visit to the country more than a decade ago, Matthew O’Brien has seen it through a different lens. His book, No Dar Papaya: Fotografías de Colombia 2003-2013, which will be released in the United States for the first time on July 20, is a refreshingly positive portrait of a nation and its people.

“As a human being and as an artist, I am drawn to beauty. I recognize beauty in all kinds of situations, and that’s what moves me. I’m not drawn to violence and misery as subject matters. … I want to create something beautiful to share with people that can maybe have a positive effect. Life’s got enough difficulties and sorrows. I think beauty makes life better,” O’Brien said via email.

Copyright Matthew O’Brien

Copyright Matthew O’Brien

Copyright Matthew O’Brien

Copyright Matthew O’Brien

In 2003, O’Brien spent more than two weeks in the city of Cartagena photographing Colombia’s national beauty pageant for his series, “Royal Colombia.” He shot the series with 35 mm color film, but he also made a few photos with his Polaroid 690, which he’d owned since the 1990s but had rarely used. When he was invited back to the country the following year to exhibit his work and teach photography workshops, he brought the Polaroid again to make portraits of the people he met. During subsequent trips, including a 2010 stint as a Fulbright fellow, O’Brien used the Polaroid more frequently to document the country the way he saw it.

“Polaroid offered a different way of working, a more deliberate approach to shooting in which you take very few images and you have to make different kinds of images than in the documentary style, and I was up for that challenge,” he said.

Through trial and error, O’Brien learned that low contrast and daytime light made for ideal Polaroid images, and he came to relish their softness and color palette. The camera’s shallow depth of field made it best suited for portraits, which make up a large percentage of the book, though he also made architectural and landscape images with it.

“I don’t get enthusiastic about digital manipulation of photographs and learning the latest tools and tricks. I’m old-school that way, and I like straightforward, well-composed photographs. So for me what was wonderful working with Polaroid is that it is pure photography—the image is how you shot it—but with a bit of the unknown and interpretive built in because you never know exactly how the colors will turn out because there is variation depending on conditions and from one pack of film to the other,” he said.

Though O’Brien believes that images of violence and suffering in Colombia serve a valuable purpose—they can be “important documents depicting real events, and they may be useful in investigations and prosecutions,” O’Brien noted—he insists it’s equally vital for the world to see images highlighting the country’s diversity and humanity.

“You can get lots of information about Colombia from other sources, but No Dar Papaya is a unique record in time that presents a vision of Colombia that you can’t find anywhere else,” he said.

Copyright Matthew O’Brien

Copyright Matthew O’Brien

Copyright Matthew O’Brien