At one time, the World’s Fair conjured up excitement about the future. What would we be doing in a few decades’ time? What would our homes and cars look like? Would we be living in outer space? Would our neighbors be The Jetsons?

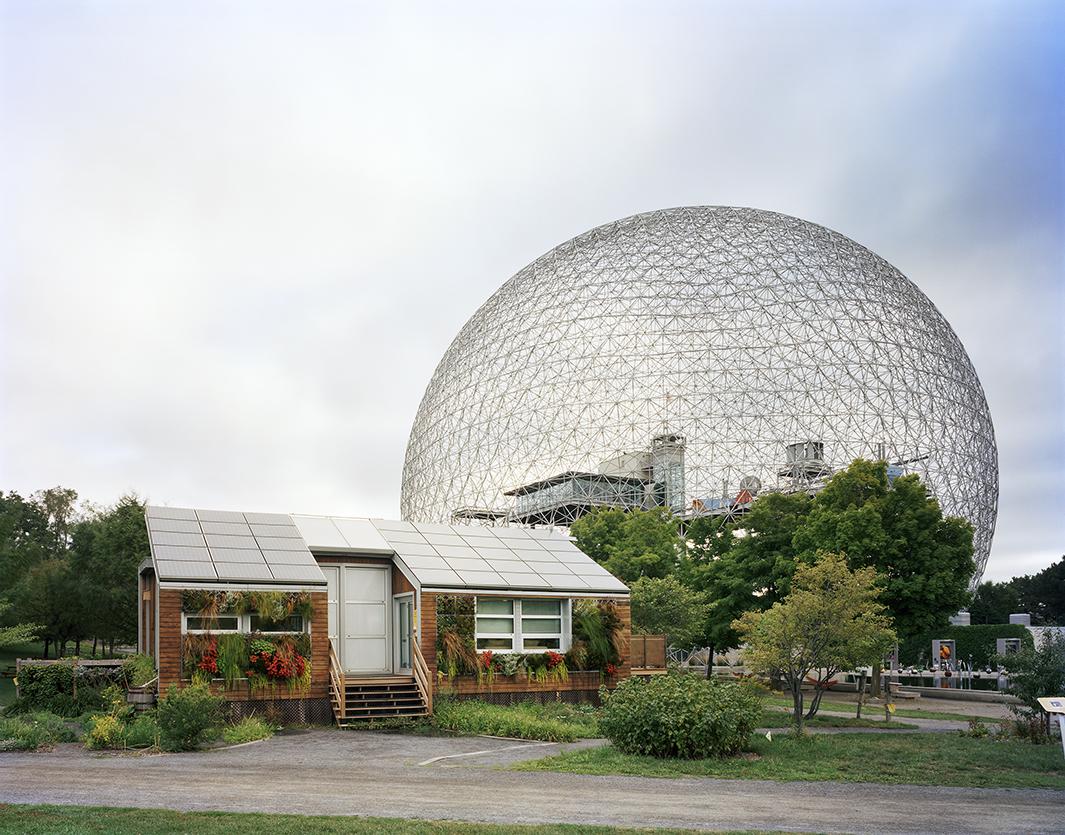

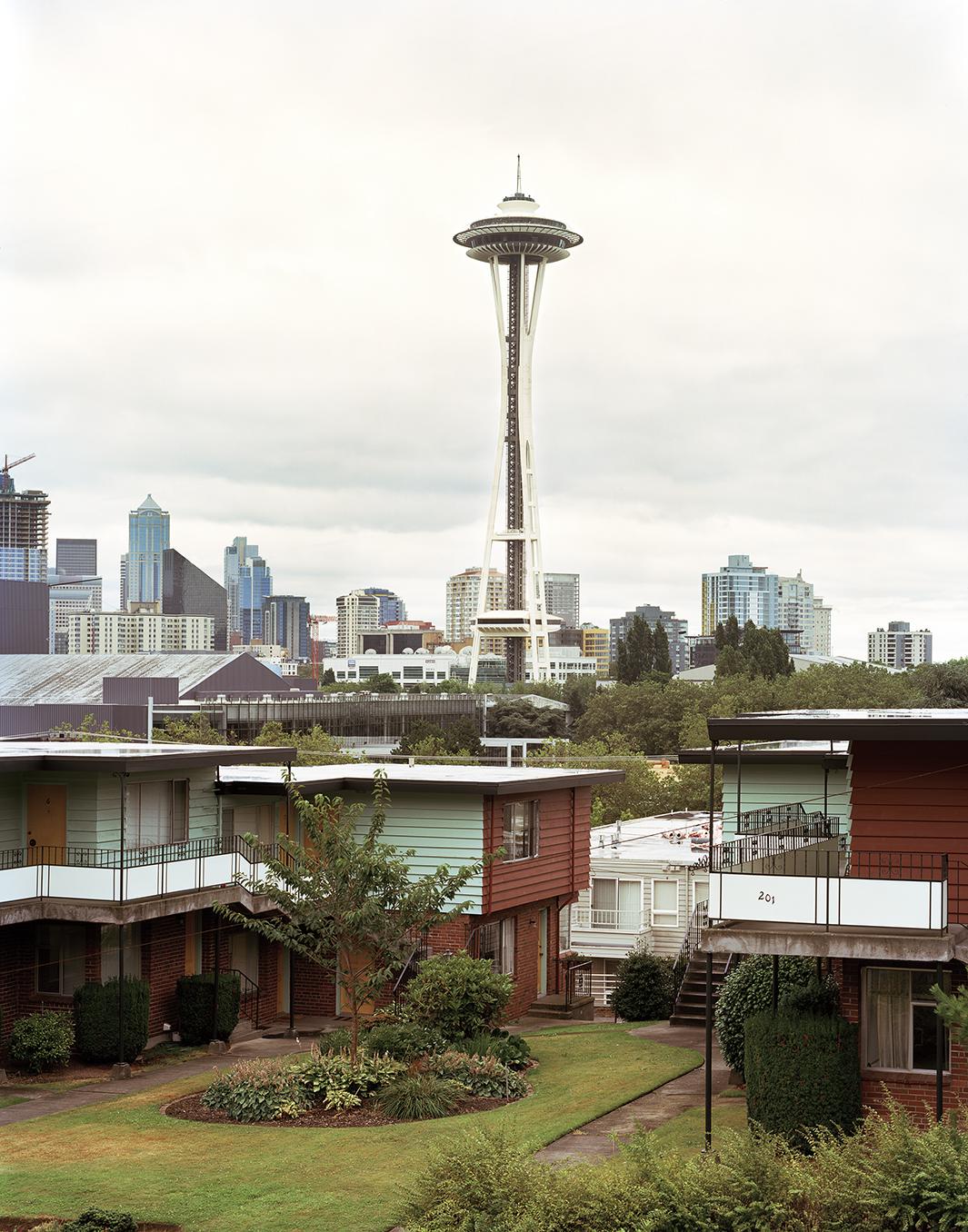

Started in 1851, the World’s Fair expositions grew in popularity and developed a kind of sci-fi edge into the mid 20th century. From the beginning, they’ve also been the birthplace for a number of iconic structures around the world, including Paris’ Eiffel Tower, the Ferris Wheel (built in Chicago), the Unisphere in New York, and the Space Needle in Seattle.

Jade Doskow has always been interested in the history of structures; she grew up in a 275-year-old house her friends would claim was haunted.

“I was always very sensitive to the aura of a place,” she wrote via email. When she was 17, Doskow moved to New York, where, like many New Yorkers, she began to notice how quickly buildings were built up and torn down. This awareness became even more acute when she moved to Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood. While studying for her MFA at the School of Visual Arts in New York, Doskow went on a family vacation to Spain and stumbled across the abandoned site of Seville’s 1992 World’s Fair.

“The strangeness of this huge site immediately struck me,” she wrote. “Acres upon acres of post-modern, once gleaming white pavilion buildings stretched as far as the eye could see.”

Jade Doskow

Jade Doskow

Jade Doskow

Jade Doskow

She had been looking for a subject for her thesis and knew focusing on the World’s Fair sites would be it. When she returned to New York, she began researching the history of the architecture and culture of past World’s Fair sites. She decided her project wouldn’t simply be a survey of the sites but instead would focus on each site’s unique situation and how it had been preserved.

“The idea of time-travel has always been a dream of mine, and I consider photographing these sites as a kind of time travel,” she wrote. “Here are these preserved notions of what the future through utopian design could hold for us, but are now overgrown, rusting, or repurposed into an office building or museum.”

Jade Doskow

Capturing the scale and immense detail of the sites required a large-format camera, she said. Using the camera also forces her to create thoughtful compositions, since the bulk and slowness of the camera calls for it.

A very deliberate photographer, Doskow said the project she has worked on for more than eight years represents both “lulls and exciting moments that are never predictable.” The project has been expensive and slow-moving, she said, but the relationships she’s developed with people involved have been inspiring.

“Over the years, an incredible energy has built around making this work, and I would not trade the difficult times for anything,” she wrote. She currently has a Kickstarter campaign that ends Tuesday, and she found a publisher, Black Dog, in London who will publish Lost Utopias this September.

Jade Doskow

Jade Doskow