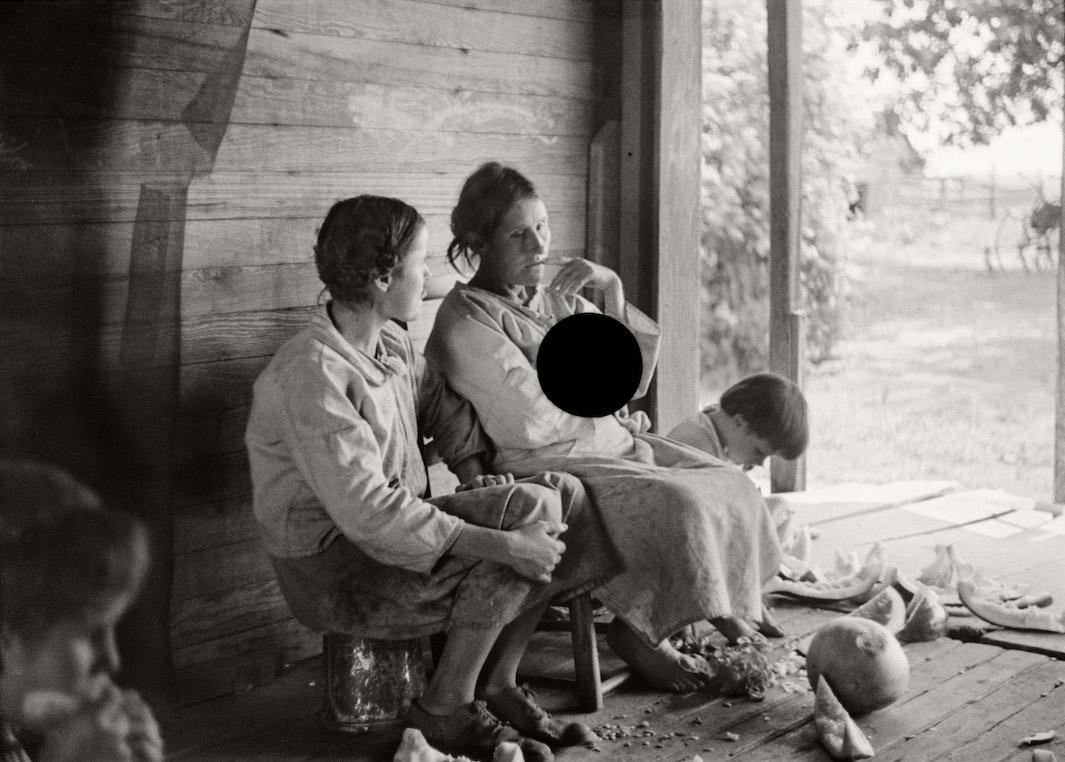

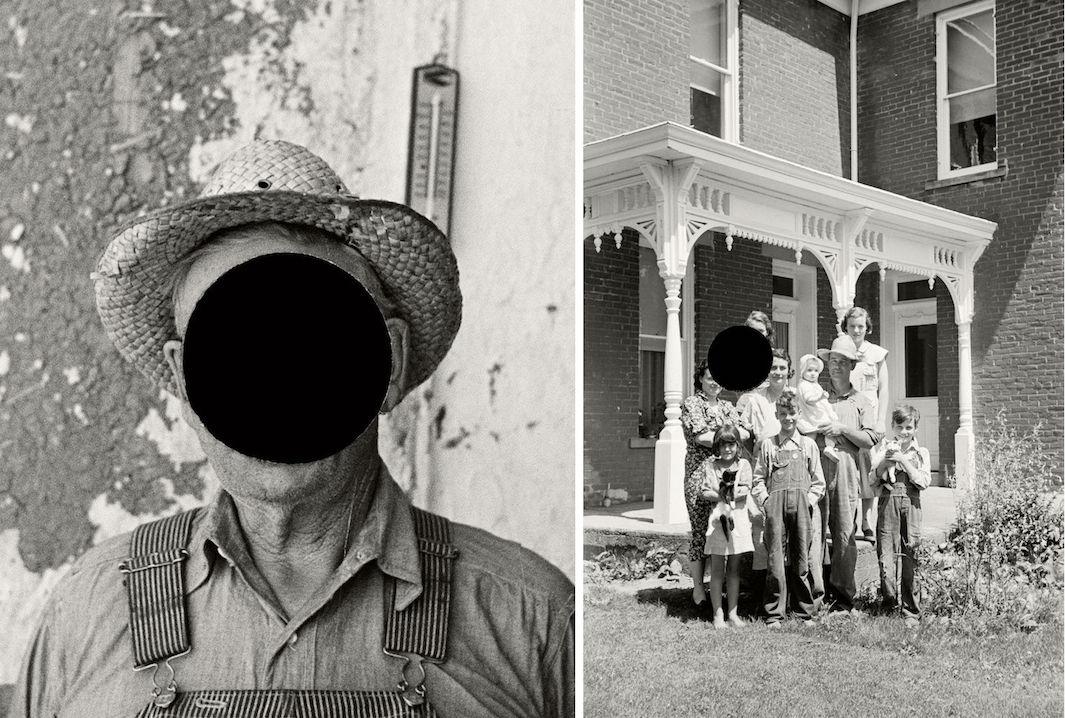

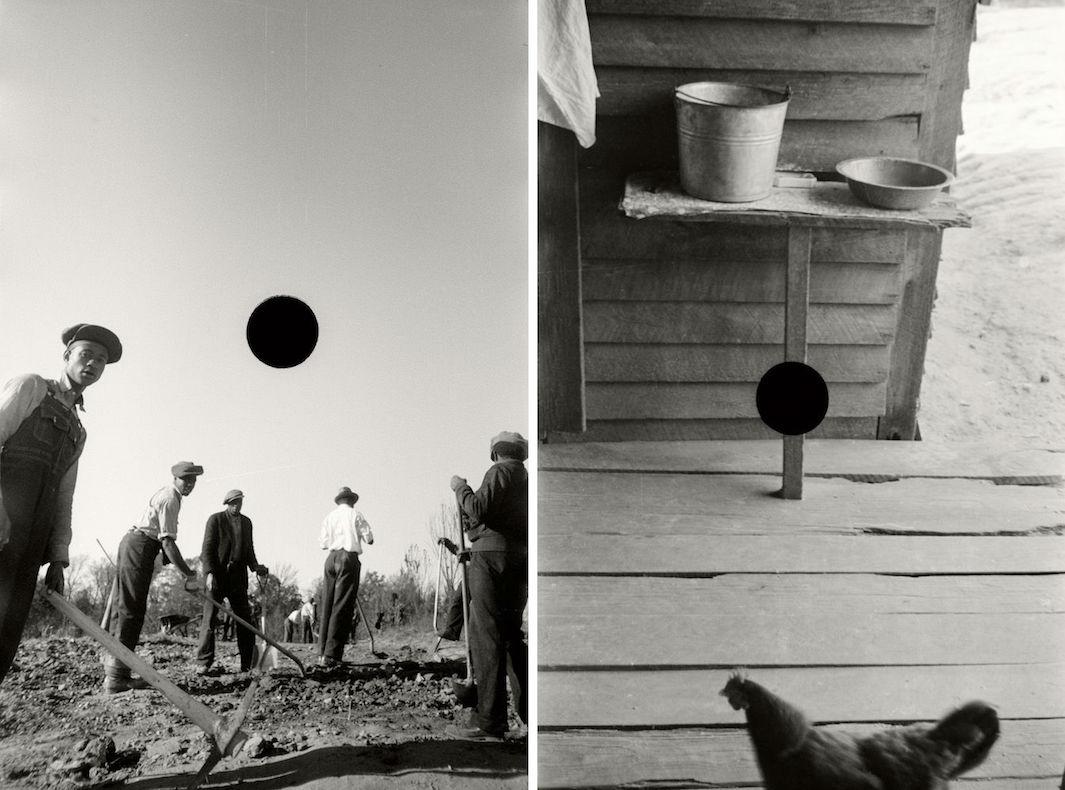

Beginning in the 1930s, the Farm Security Administration was responsible for combating rural poverty in America. By hiring photographers to document its work and promote its mission, it was also responsible for commissioning some of the most iconic images of the Great Depression from photographers including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks.

The driving force behind those assignments was Roy Stryker, an economist and photographer who served as the head of the agency’s documentary photography program. He was a powerful and tough editor. With his approval, a photo could enter the annals of photography history. Without it, an image faced total destruction. That’s because Stryker had the infuriating habit of “killing” photographs he didn’t intend to use by hole-punching straight through the negatives, resulting in a large black void when printed.

After spotting one of these damaged images in a magazine, photographer Bill McDowell started searching through the FSA’s online archive for others in 2009. While he said he was “horrified at the hubris” of Stryker’s destructive act, he became curious about the strange and captivating ways in which the black holes altered the meaning of the images. The holes struck him as a “contemporary mark,” he said, like those intentionally used later in the century for artistic purposes by artists such as John Baldessari and Thomas Barrow. McDowell’s selection of images from the archive is now collected in Ground, which Daylight Books published in April.

“While the existence of Ground is predicated entirely on Roy Stryker’s hole punch, the book is not intended to be about his callous editing. Nor is it a historical picture book of Depression-era photographs. I hope Ground can be viewed as a meditation on our past, communicated through a sequence of archival photographs that, due to the nature of their incompleteness (the black hole), speak also to the present,” McDowell said via email.

Carl Mydans/Library of Congress

Ben Shahn/Library of Congress

Walker Evans/Library of Congress

When McDowell started his curatorial process, the United States was in the midst of the Great Recession, which made him think about what we had in common with Americans suffering economic hardship in the 1930s. As a result, many of the photographs he selected relate to basic needs we share with the past—such as food, shelter, and water—and draw a poetic comparison between disparate eras. Generally, McDowell looked for photos in which the black hole changed the way the subject resonated, either aesthetically or emotionally. Often, it can seem that the hole’s placement might have been intentional, but McDowell said that’s unlikely. Meaning, in this case, is manufactured through McDowell’s own careful editing.

“I think their only intent was to make a negative unusable. Pure and simple. Many negatives have two or three holes punched in them or were canceled by using a grease pencil. And keep in mind, these were 35mm negatives—they’re not very big. So one would have had to be very careful and precise to deliberately position the hole punch. They weren’t making pictures. But it’s fascinating to see in Ground how often the hole’s placement within a photograph appears to be ‘thoughtful,’ ” he said.

Left: Russell Lee/Library of Congress. Right: Arthur Rothstein/Library of Congress.

John Vachon/Library of Congress

John Vachon/Library of Congress

Left: Carl Mydans/Library of Congress. Right: Walker Evans/Library of Congress.