When Sara Davidmann’s mother, Audrey, moved into a nursing home in 2011, Davidmann discovered a trio of folders that contained an epistolary family history, centered around Audrey; Audrey’s sister, Hazel; and Hazel’s husband, Ken. Written across one of the three folders that held the letters was written, “Ken. To be destroyed.”

Inside, Davidmann and her brother read letters about Hazel and Ken’s life together, which began as pen pals and evolved into a marriage that, in the 1950s, was rooted in a secret that Ken had come out as transgender.

Audrey had shared this secret with Davidmann in 2005, a couple of years after Hazel had died (Ken died in 1979), and she had asked her daughter to keep the information private. As a coincidence, Davidmann was finishing a Ph.D. in collaborative photography at London College of Communication, and the bulk of her work had focused on the queer and transgender communities in London.

“It’s actually very lucky I had been working in the trans communities in the United Kingdom,” Davidmann said. “If I hadn’t, I probably wouldn’t have been interested in the material, I think. It made me realize how important the material was and how interesting it was and how important it was for me to be open about the fact there was a transgender person in my family in the 1950s.”

Sara Davidmann

Sara Davidmann

Sara Davidmann

When Hazel died, Davidmann’s mother inherited the letters, which she then carefully edited. “There are very specific things she kept,” Davidmann said. “But there’s always a question with archives about what’s missing.” The letters between the sisters and Ken address Ken’s coming out as transgender, the dual life he lived (publicly as a man but at home as a woman) and the difficulties and feeling of isolation this presented for everyone.

“What’s great about those letters is everyone was trying to support each other, there was no sense of blame or thinking things were wrong,” Davidmann said. “My mother was just trying to find out what to do about supporting Hazel. … It was incredible to find out about this family secret that had been kept hidden for so long; I felt it was a great shame when I was younger I hadn’t known about all of this. It would have meant a lot to me to know about it; it’s a great shame that in families we keep so much secret from each other.”

Sara Davidmann

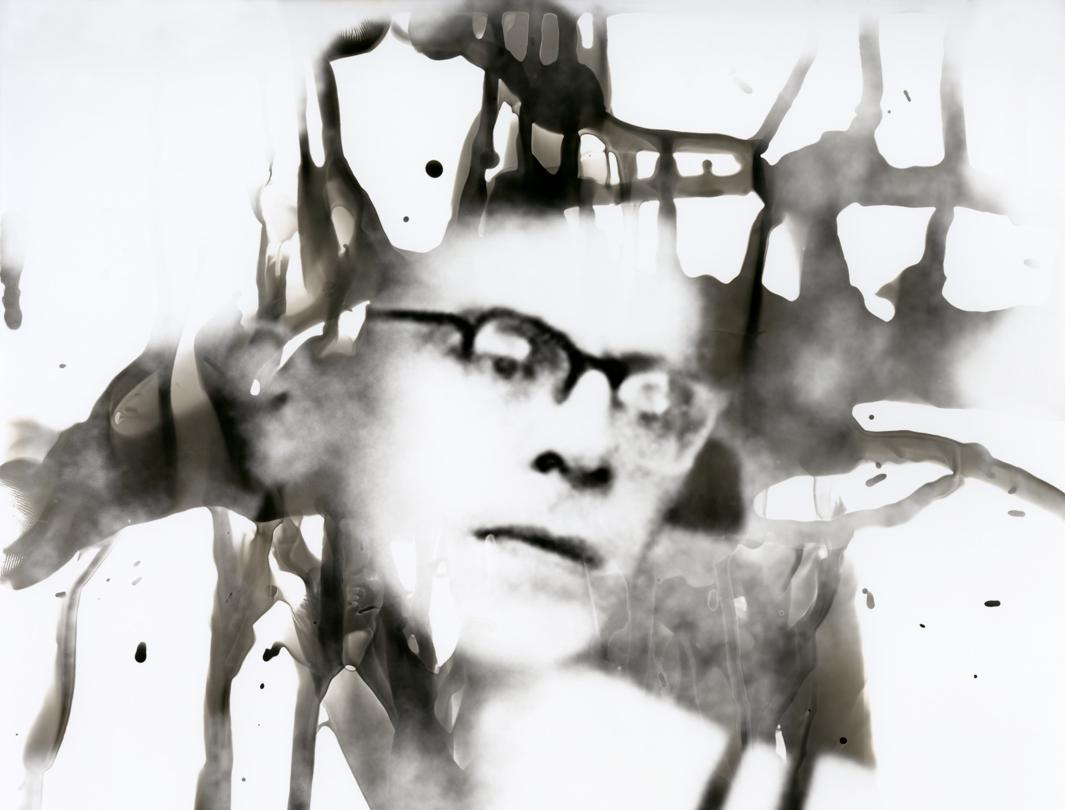

Davidmann decided to create a body of work about the letters. She began photographing the letters themselves, as well as photographs of Ken and Hazel. Using analog, alternative, and digital processes, Davidmann started to repurpose and reimagine the life that Ken might have been living. Davidmann said she usually doesn’t release her work until she feels it’s complete, but for this project, she did the opposite, sharing the work as she made it. But the project is still ongoing: An exhibition of the work is currently on view at Schwules Museum in Berlin until June 30, and Schilt published the work as a book, edited by Val Williams, titled Ken. To be destroyed.

The timing of the book’s release has also been a happy coincidence, as trans visibility has grown significantly in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States.

“I think it’s such a positive thing—it’s so needed—but there is still so much that needs to be improved as far as gaining respect for transgender people and for equality. So much needs to be done, but things are shifting, and it’s a great time actually.”

Sara Davidmann