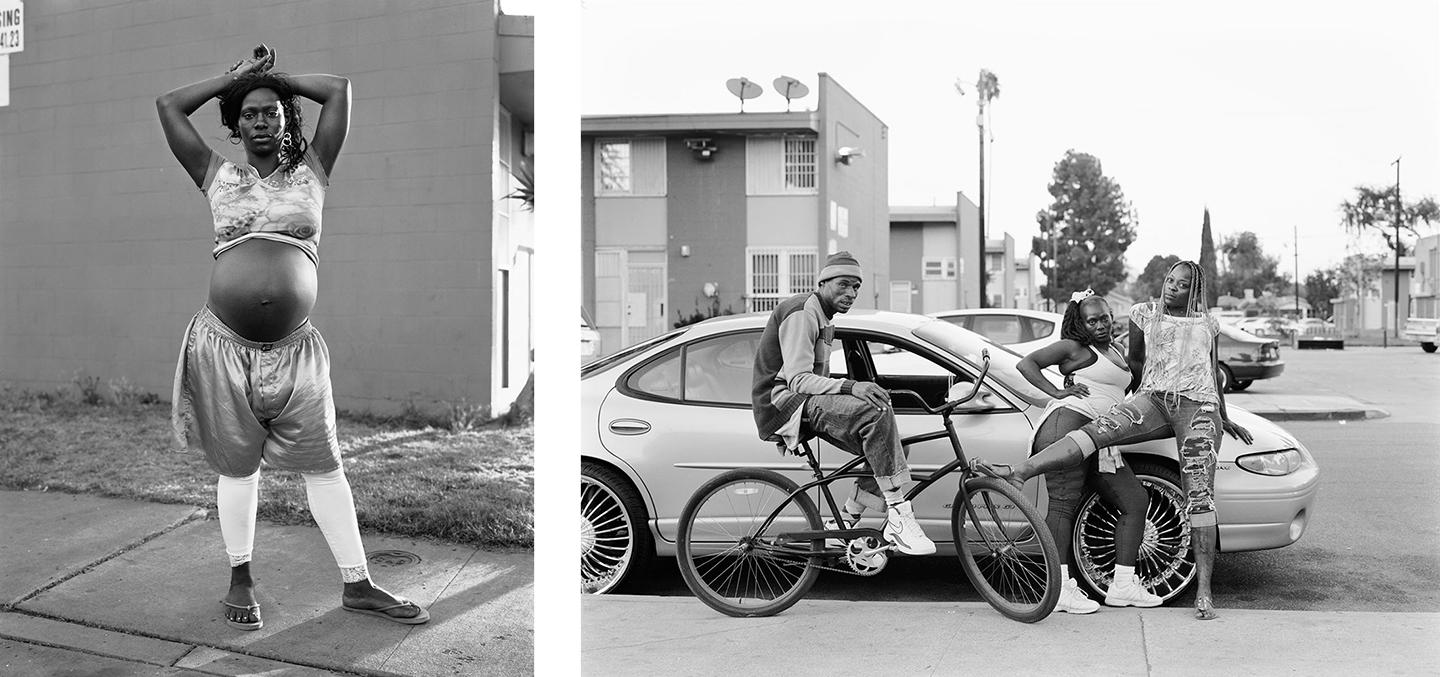

Dana Lixenberg came to Los Angeles in 1992 on assignment for a Dutch magazine to cover the city’s rebuilding after the riots that followed the Rodney King verdict. She returned with a curiosity to learn more about gang culture and what life was like in housing projects.

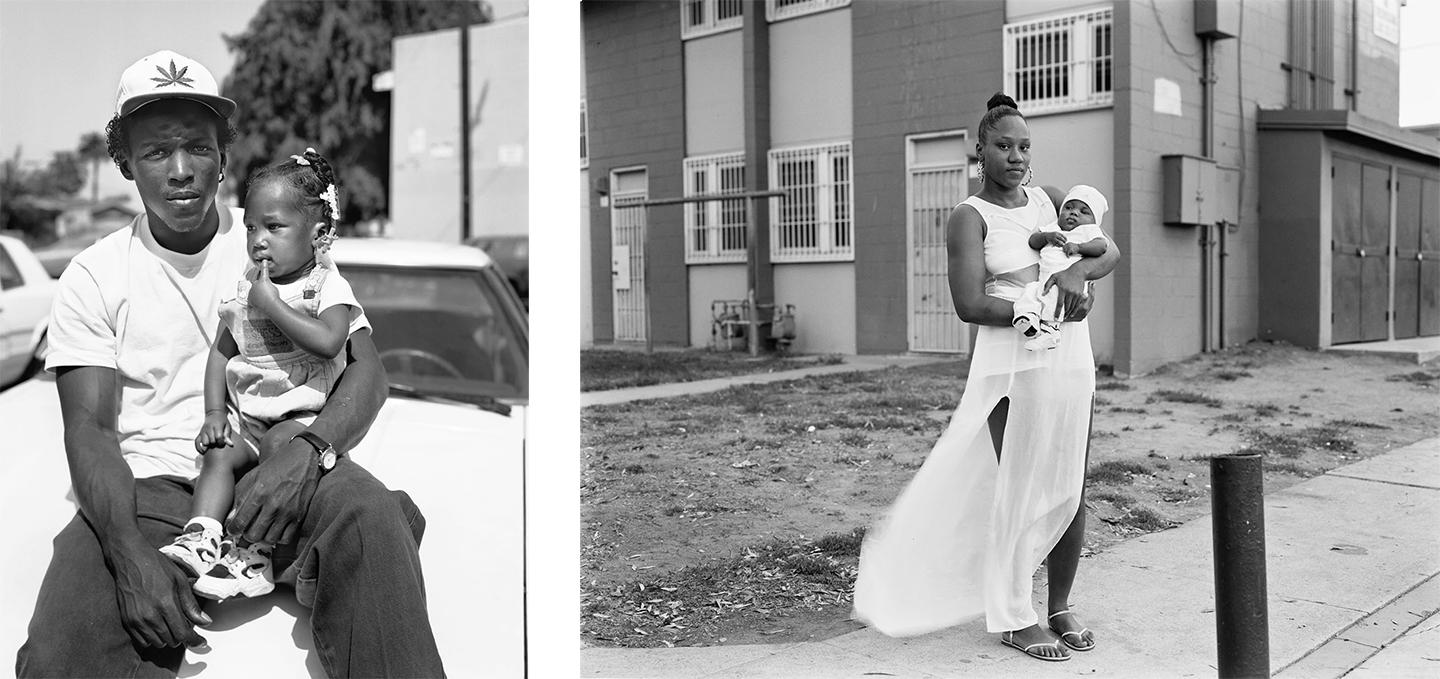

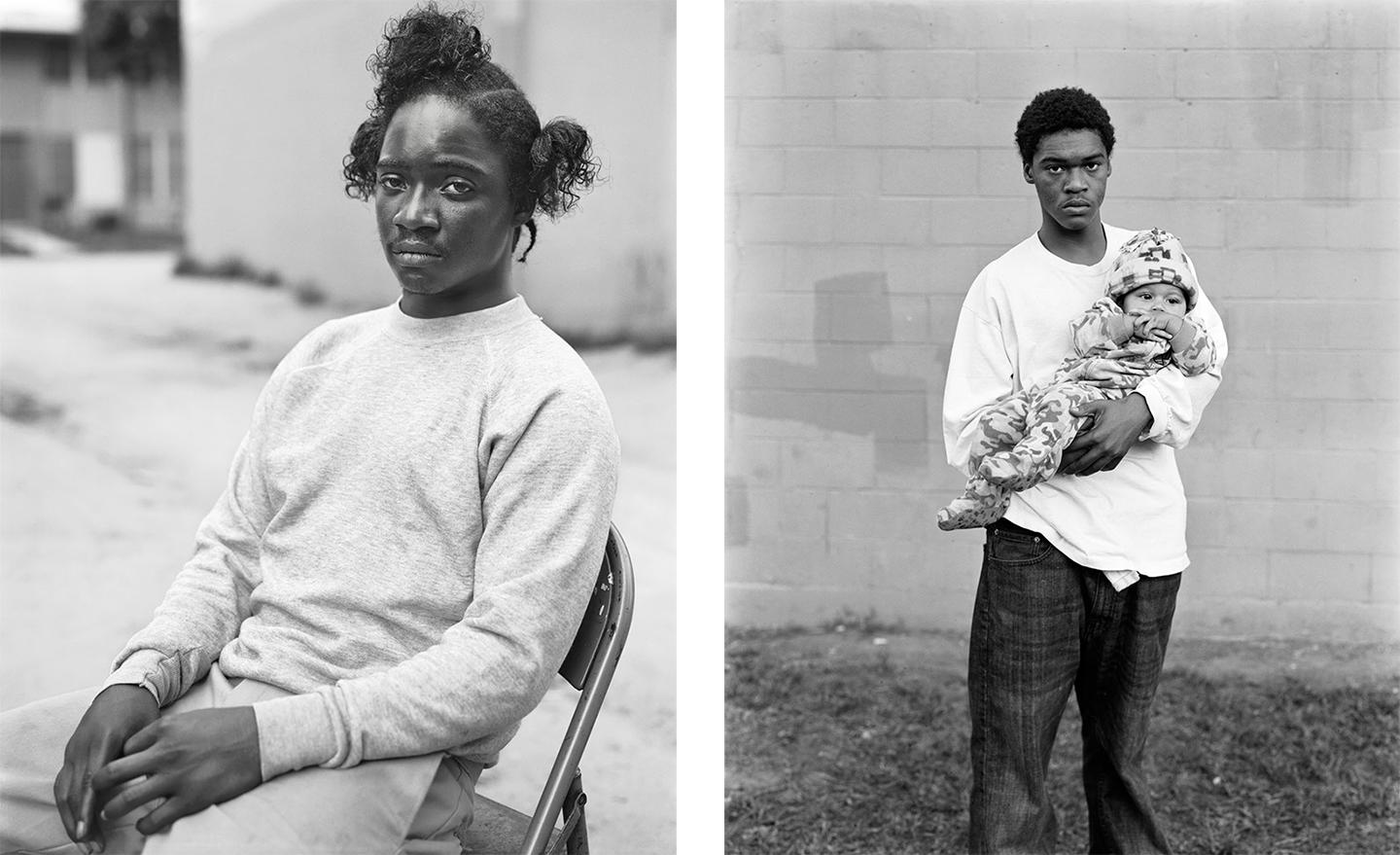

Her book, Imperial Courts, published in 2015 by Roma, is a study of the individuals who live in the Imperial Courts project. As she photographed her subjects and their families over a 22-year period, it evolved into a kind of yearbook.

While working on the initial assignment, Lixenberg had met members of the Black Carpenters Association (a collective of contractors and activists) who had in turn introduced her to Tony Bogard, then a leader of the Imperial Courts PJ Watts Crips, “the unofficial godfather of the community.” Bogard was reluctant to be photographed, but he eventually introduced Lixenberg to the Imperial Courts project and to many of the residents who lived there.

The work, which was done with a 4-by-5 camera instead of the 35 mm one Lixenberg had previously used, shaped the way Lixenberg would view both portraiture and her place within the photographic community.

“Things really fell into place when I did this project and started working with this camera,” she said. “I found my language and voice of a photographer through this project.”

Dana Lixenberg

Dana Lixenberg

Dana Lixenberg

Lixenberg showed the work and was awarded a grant from the Mondriaan Fund, which she used to buy a new camera and to get herself to Los Angeles for a month. She wanted to create work that showed a more human, individual angle that was radically different from the media’s often stereotypical portrayal of life in the projects.

“I feel context is important, but it’s also about the person,” Lixenberg said. “I think that’s why I gained their trust. It’s more about photography and creating images that resonate and of course tell a story. I wasn’t interpreting their story.”

Although Lixenberg wasn’t certain in what direction the project would be headed, she felt working with a slow, cumbersome camera, as well as her interest in observing people—she had considered a career in psychology at one point—made a big difference in paving the way for people to begin to trust what she was doing; as the project evolved she went from being known as “the picture lady” to “Dana.”

“With any creative medium, you’re partly trying to make sense of the world around you and to find your own position in it,” she said. “Photography is a very direct way to connect to life around you.”

Dana Lixenberg

The work Lixenberg created during that month was exhibited in the Netherlands and subsequently appeared in Vibe. A few years later, it was shown for the first time in the United States. Feeling the photographs were about a specific time and place and that it was complete, Lixenberg put it to rest for 15 years.

But the residents of Imperial Courts were interested in continuing the conversation, and Lixenberg returned in 2008. Aesthetically, little had changed in the projects themselves, but life had moved on for her subjects: Some had children, some had died or were in jail, and as attention on how black Americans were treated within the United States began to reach the mainstream media, so too did the importance of continuing to tell the stories of the people she had met. Although she wanted to create new, unique portraits, Lixenberg expanded the project to include environmental images and also added a video in order to present an idea of daily life—both visually and audibly—in the projects. Lixenberg returned again in 2015 and feels that while the book and video are now finished, she still has a strong connection with her subjects, many of whom had been looking forward to seeing the images published as a book.

“I’ll never be finished there in a way,” she said. “I need a little bit of a break, but I feel my relationship with the community will continue no matter what, and part of our relationship is to produce more work. It was a very special moment for me [to distribute the book] and I hope for them, too. When we presented the books, they organized a barbecue at Imperial Courts, and we had a party, and I put the books in people’s hands; they were like, Dana you did it!”

Dana Lixenberg

Dana Lixenberg

Dana Lixenberg