Walker Evans may be best known for his 1935 and 1936 Farm Security Administration documentary photos, but he had a long career that explored a range of styles and techniques. Walker Evans: Depth of Field, which Prestel published in November, provides the most comprehensive book-length look yet at the work of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

“Looking over Evans’ entire career shows an artist who was constantly evolving; he was sampling new ideas, techniques, and technologies. Anything new or curious was of interest. When he advised the artist to ‘Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop,’ he was speaking from his own experience. It could have been his personal mantra,” said John T. Hill, a photographer and friend of Evans who edited the book with Heinz Liesbrock, via email.

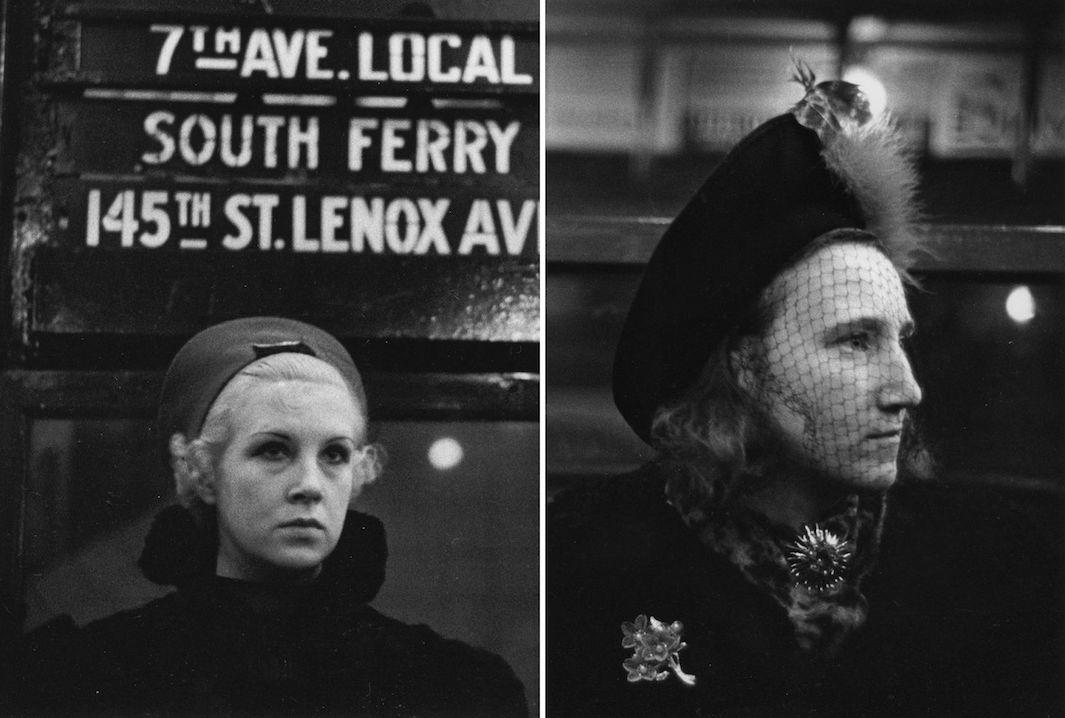

Copyright Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

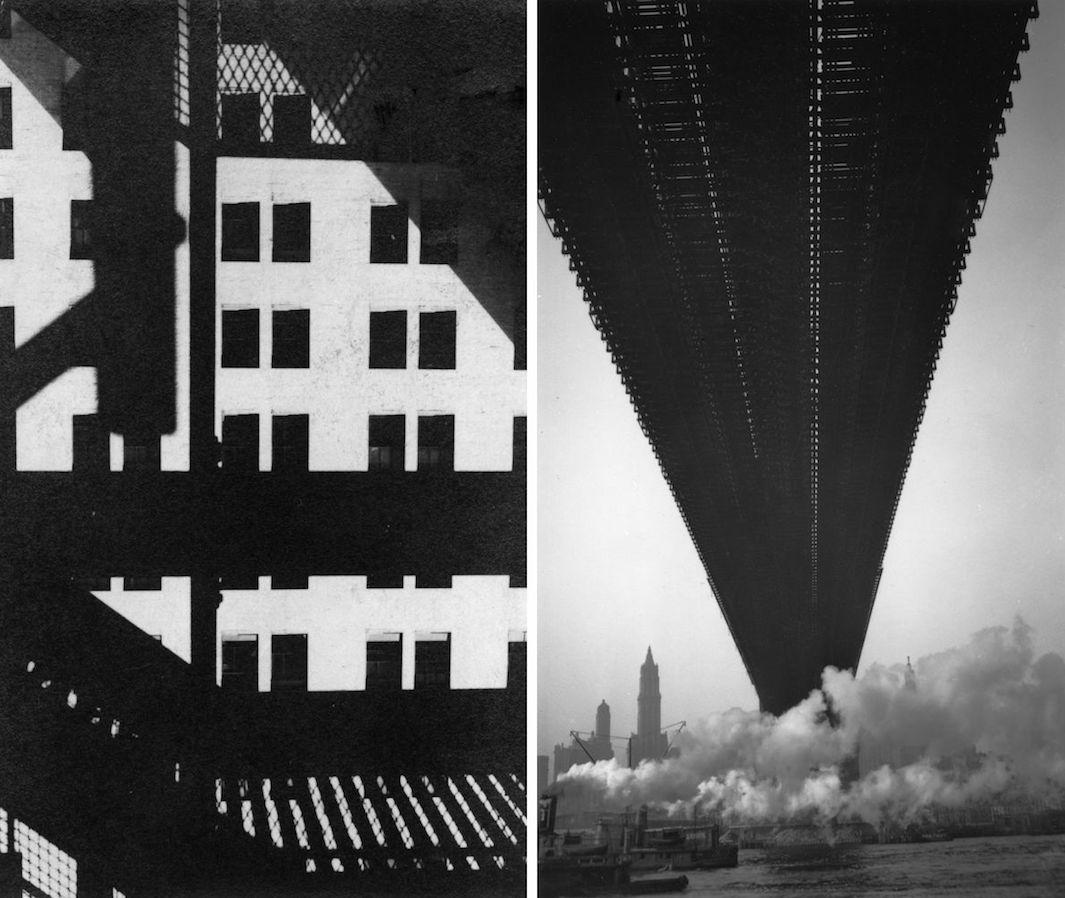

Private Collection, Copyright Public Domain

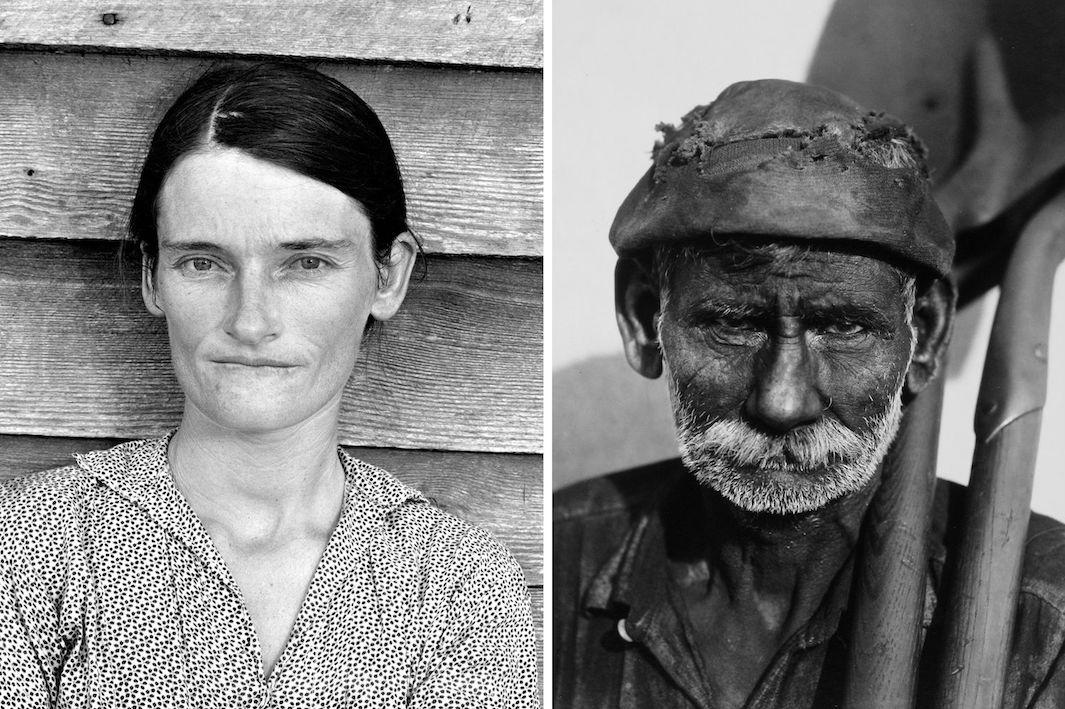

Evans was born in St. Louis in 1903 and started taking architectural, abstract photos while studying in Paris in 1926. Within a year of moving to New York, Hill said, the self-taught photographer was making “remarkably mature” street portraits with a Leica, whose quality rivaled those of French master Henri Cartier-Bresson. By the early 1930s, Evans had adopted a straightforward documentary style, which characterized his famous FSA photos recording the impacts of the Great Depression. This, like most of his work, was the result of a paid assignment.

“Evans had no fear of being tainted by commercial work. He knew that once he had been given an assignment that he could shape it to satisfy his own artistic sense. For me, this is one of Evans’ claims to genius—that was knowing that he could have the work on his own terms,” Hill said.

After he left the FSA in 1938, Evans gave up his 8-by-10 large-format camera for a while and began trying other cameras and techniques. One of his most successful experiments came when he took a concealed 35 mm camera into the New York City subway system and photographed anonymous portraits without looking through the viewfinder. It was an approach he’d use again for other projects, including a series, “Labor Anonymous,” on workers in Detroit for Fortune magazine. His last major body of work, in the 1970s, was made with a Polaroid SX-70, which demonstrated his interest in exploring color and nonprofessional camera technology.

Copyright Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Copyright Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The unifying factor of Evans’ oeuvre may be its rejection of the establishment’s concept of fine art. Unlike some of his peers, Evans took tabloids, newsreels, post cards, and vernacular advertising as his inspiration instead of painting. This way of looking at the world has come to influence many photographers and, moreover, the art world itself.

“Once you are immersed in Evans’s work, it is hard to see the world the same as before. You find less interest in the celebrity, the sensational, and the search for fine art. Evans taught several generations of us to not look for the classically beautiful subjects but to look for what we could find in the most ordinary.”

Copyright Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Left: Private Collection, Copyright Public Domain. Right: Copyright Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.