Gordon Parks was always a photographer with a mission.

“I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapon against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty,” the legendary photojournalist once said.

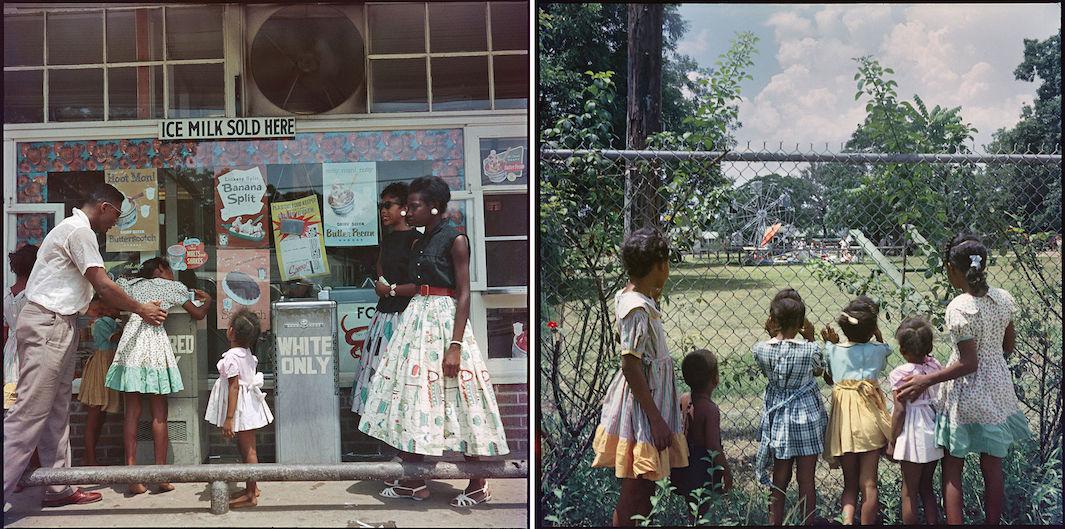

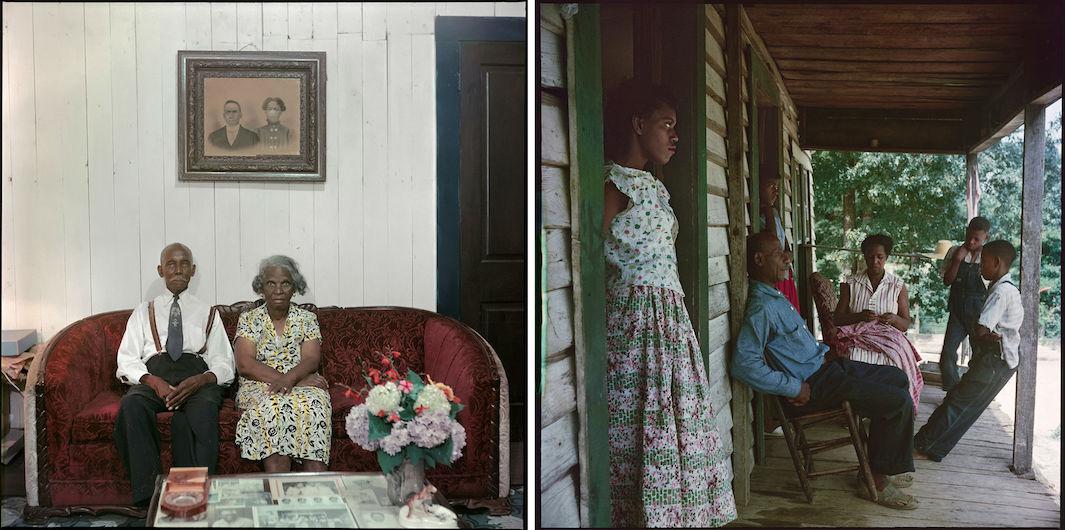

Parks’ philosophy is eloquently expressed in his photo essay, “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” which ran in Life magazine, where he was the first black photographer on staff, in 1956. In Mobile, Alabama, and beyond, he documented the everyday lives of Albert Thornton and his wife as well as their nine children and 19 grandchildren, who comprised the Causey and Tanner families. At the time, most of the media coverage of the civil rights era centered on political demonstrations and violence. Parks, however, highlighted the injustices of the Jim Crow era—just as, in 1950, he demonstrated the consequences of school segregation in work that we featured earlier this year on Behold—not with spectacle but with the everyday.

“He didn’t want to go to the South and take images of people protesting or people being angry or people looking really poor and destitute. He wanted to generate a feeling of empathy in the readers of the North, so they’d see the images in the story and relate to the daily activities of the people that they saw in the magazine,” said Fabienne Stephan, director and curator of New York’s Salon 94 Freemans, which is showing Parks’ photos in an exhibition, “Segregation Story,” through Dec. 20.

By following multiple generations of this one family, Parks showed how segregation touched the lives of black Americans of diverse experiences. Its patriarch, 82 at the time, was the son of a slave and told the magazine’s Robert Wallace that life for blacks had improved little since his own childhood. Thornton’s daughter Allie Lee Causey, was working as a teacher in a ramshackle schoolhouse “almost as primitive as the log cabin schools of a century ago” in Shady Grove, Alabama. Her brother E.J. Thornton, a professor at Tennessee State University in Nashville, was not able to mingle with white professors at other colleges and found segregation as demoralizing as the rest of his family.

Gordon Parks, courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation and Salon 94, New York

Gordon Parks, courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation and Salon 94, New York

While Parks aimed to show the dignity with which his subjects went about their lives at home, at church, and in town, he took care to underscore the unfairness of a second-class existence. He photographed Causey’s dilapidated school, the two-room shack that Thornton’s granddaughter Virgie Lee Tanner, shared with the other five members of her family, and, wherever possible, the “white” and “colored” signs that split American society in two.

“You go into town and are reminded every minute that you’re different. You go to the water fountain, you’re different; you go to the cinema, you’re different; you go to get ice cream, you’re different. It’s at every turn,” Stephan said.

Parks’ essay wasn’t just about denouncing segregation. It was, in a way, also about imagining the possibilities of a world in which blacks were treated equally. Causey, like her father, hoped for the end of segregation, and she personally believed it was “on the way out.” Once the laws changed, she told the magazine, life was sure to improve.

Gordon Parks, courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation and Salon 94, New York

“Integration is the only way through which Negroes will receive justice. We cannot get it as separate people. If we can get justice on our jobs, and equal pay, then we’ll be able to afford better homes and good education,” she said.

Gordon Parks, courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation and Salon 94, New York