After the Russian Revolution, artists, many of them Jews enjoying their freedom from czarist anti-Semitism, turned to photography to document their young state. As the Soviet Union’s leadership changed, however, so did its photography. This progression is shown in the exhibit “The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film,” which is on display at New York’s Jewish Museum through Feb. 7.

Since 70 percent of the Soviet Union was illiterate, according to exhibit co-organizers Jens Hoffmann and Susan Tumarkin Goodman, photos and film were the preferred propaganda tools for the Communist government in the 1920s.* Initially, avant-garde photographic techniques were encouraged.

“Radical style was seen as the expression of radical politics. For a time, artistic invention operated in potent and fruitful synergy with activism,” Hoffmann said via email.

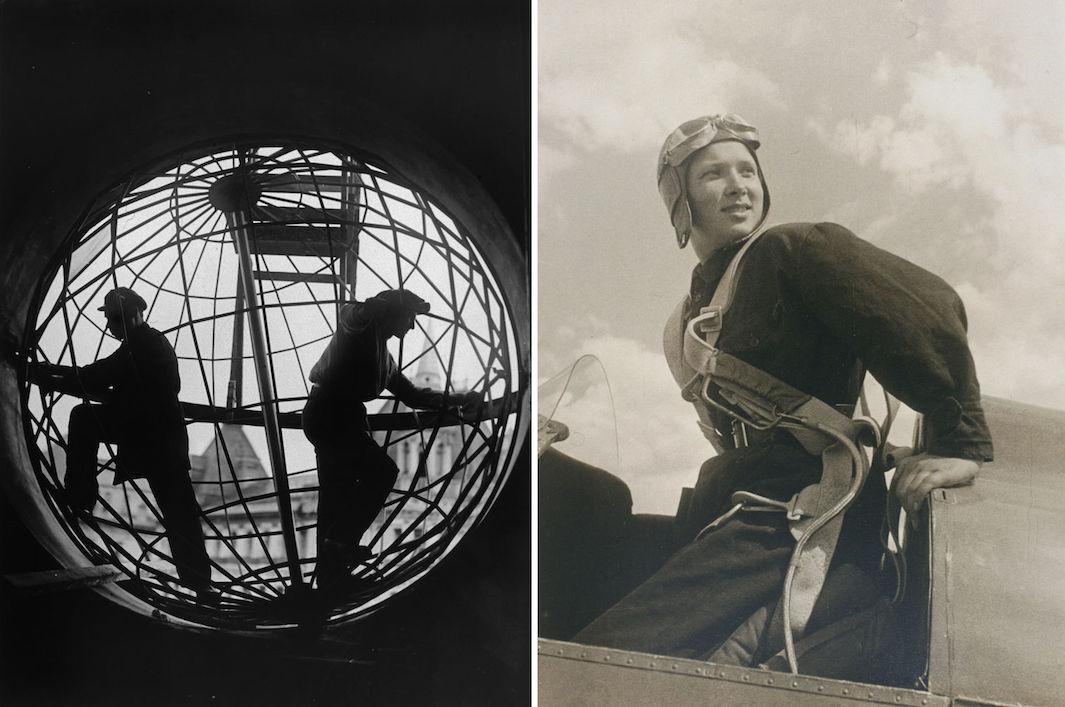

Copyright Estate of Alexander Rodchenko (A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive) / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York.

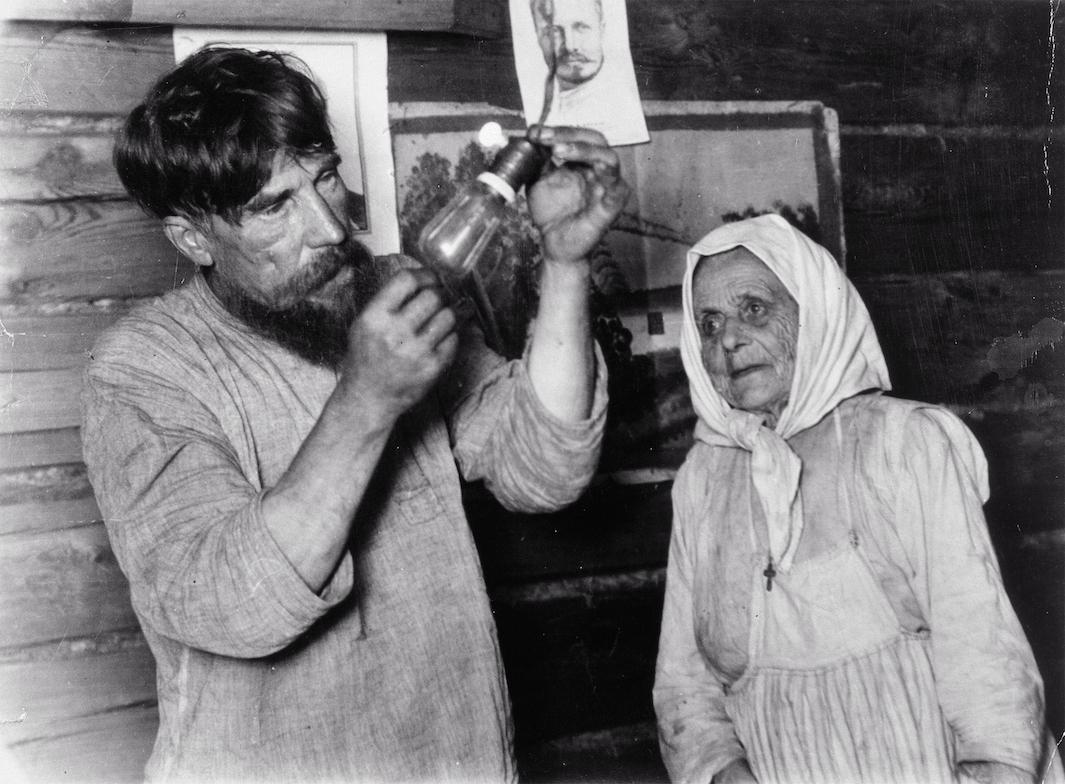

Copyright Estate of Arkady Shaikhet, courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery.

Copyright Estate of Arkady Shaikhet, courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery. Image provided by Rosphoto, State Russian Centre for Museums and Exhibitions of Photography, St. Petersburg.

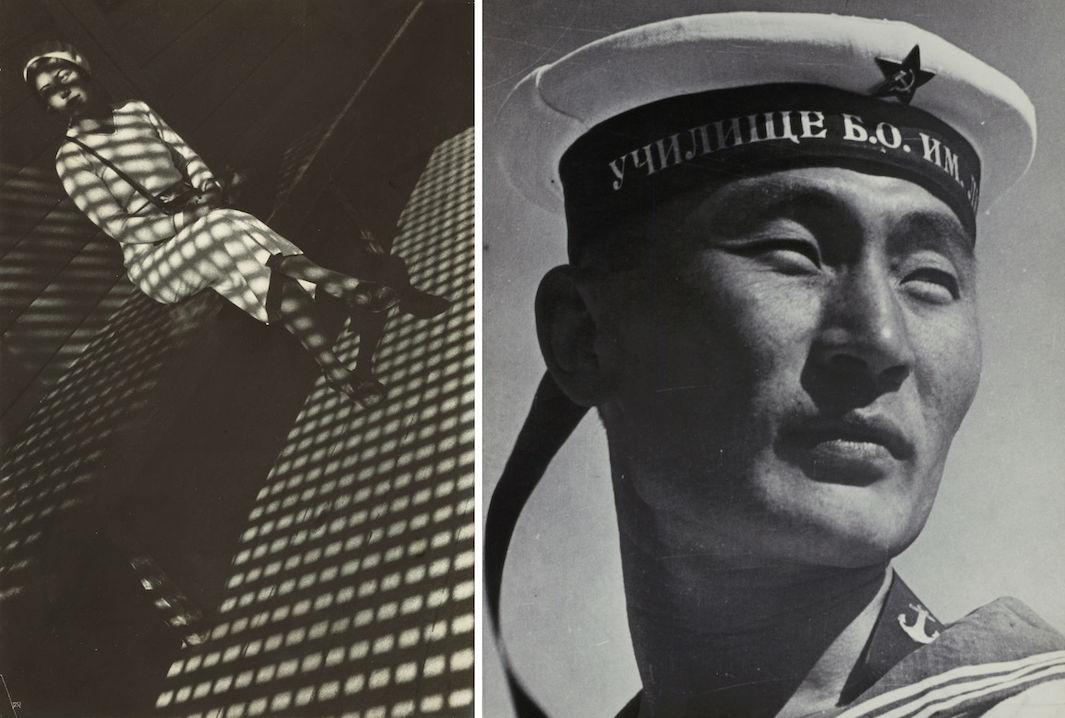

Left: Copyright Estate of Arkady Shaikhet, courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery. Right: Copyright Estate of Arkady Shaikhet, courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery.

Two important professional organizations for photographers emerged in the early days of the Soviet Union: The group October and the Russian Association of Proletarian Photographers, or ROPF. Members of October, including constructivist photographer Alexander Rodchenko, wanted to create images that would inspire viewers to see society in a new way.

“Imbued with revolutionary spirit, these photographers actively engaged in avant-garde art experimentation, making use of unexpected and dramatic vantage points, startling angles, photomontage, and photograms. For example, October photographers, urged to document industrialization, showed industrial sites in radically abstracted close-ups or compressed into a limited visual space,” Hoffmann said.

Rodchenko’s work and the work of other constructivist photographers like El Lissitzky and Boris Ignatovich influenced photojournalists, including those who made up the ROPF. But the avant-garde’s prominence in Soviet imagery was soon curtailed. In the 1930s, with Joseph Stalin in power, Soviet photography shifted as photographers were forced to make images illustrating the perfection of Soviet life and government rather than the reality on the ground. By 1932, independent styles were no longer tolerated, and artistic organizations were dissolved and replaced by state-run unions.

“The period of intense innovation was brief,” Goodman said via email.

Correction, Nov. 13, 2015: This post originally misspelled Jens Hoffmann’s last name.

Sepherot Foundation, Vaduz, Liechtenstein.

Left: Copyright Estate of Alexander Rodchenko (A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive) / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York. Right: Copyright Georgy Petrusov, courtesy of Alex Lachmann Collection. Image provided by Rosphoto, State Russian Centre for Museums and Exhibitions of Photography, St. Petersburg.

Copyright Estate of Arkady Shaikhet, courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery.

Copyright Estate of Arkady Shaikhet, courtesy of Nailya Alexander Gallery.

Left: Image provided by Rosphoto, State Russian Centre for Museums and Exhibitions of Photography, St. Petersburg. Right: Copyright Estate of Alexander Rodchenko (A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive) / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York. Image provided by the Sepherot Foundation.