For those who don’t live there, the vast, dry and sparsely populated places west of the 100th meridian are often considered part of American “flyover country”—a landscape one might cursorily view from an airplane headed elsewhere but never visit. Andrew Moore, however, was motivated to take a closer look when he took a fateful photo at a cattle branding in Keene, North Dakota, in 2005.

“There was a circle of cattle and calves surrounded by horses, men, women, children, and dogs—a geometric, beautiful formation of harmony within the landscape. It was a powerful photograph for me; it had this mythic quality. I thought, ‘Wow, there’s something to be made here about the relation of man and nature in this landscape,’ ’’ he said.

Copyright Andrew Moore

Copyright Andrew Moore

Copyright Andrew Moore

That image became the inspiration for a full decade of photography in the region. In his book, Dirt Meridian, which Damiani published in September, Moore presents photos from his travels through parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and the Sand Hills of Nebraska, all of which lie west of the longitudinal line that bisects the country.

“It’s the spiritual heartland of America—this empty space, this boundlessness, the sense of possibility. This place inspires imagination. I hope [readers] come away with the idea that there’s more there than they imagined, and that it’s part of the American character, the American mythology,” he said.

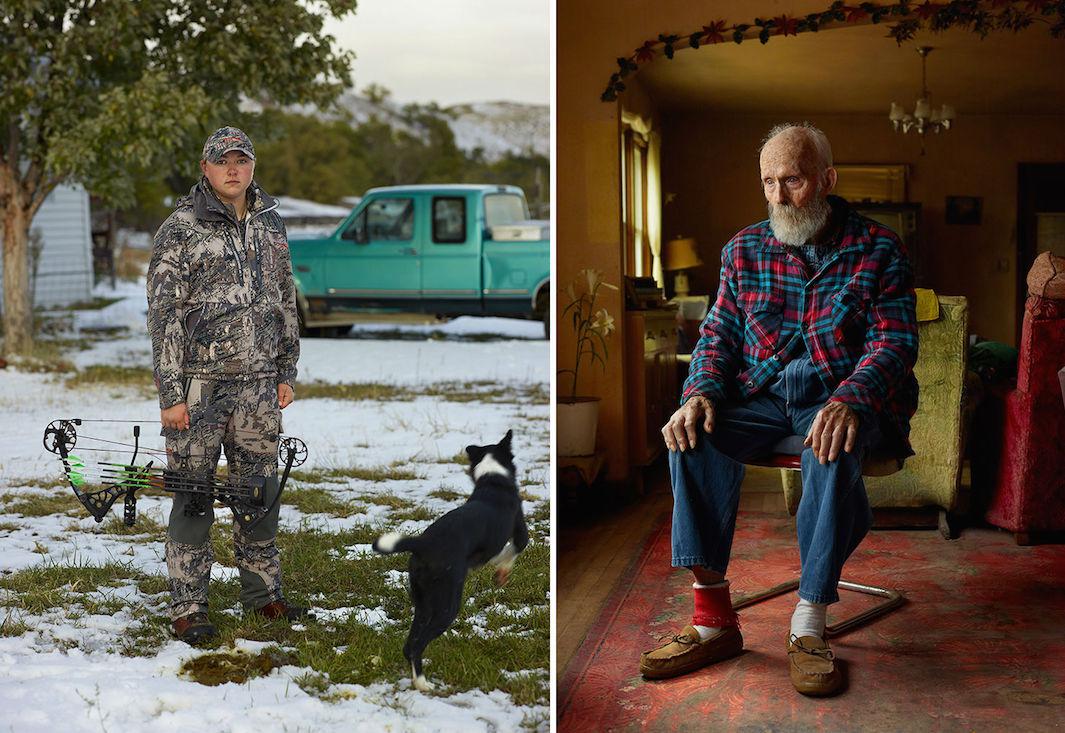

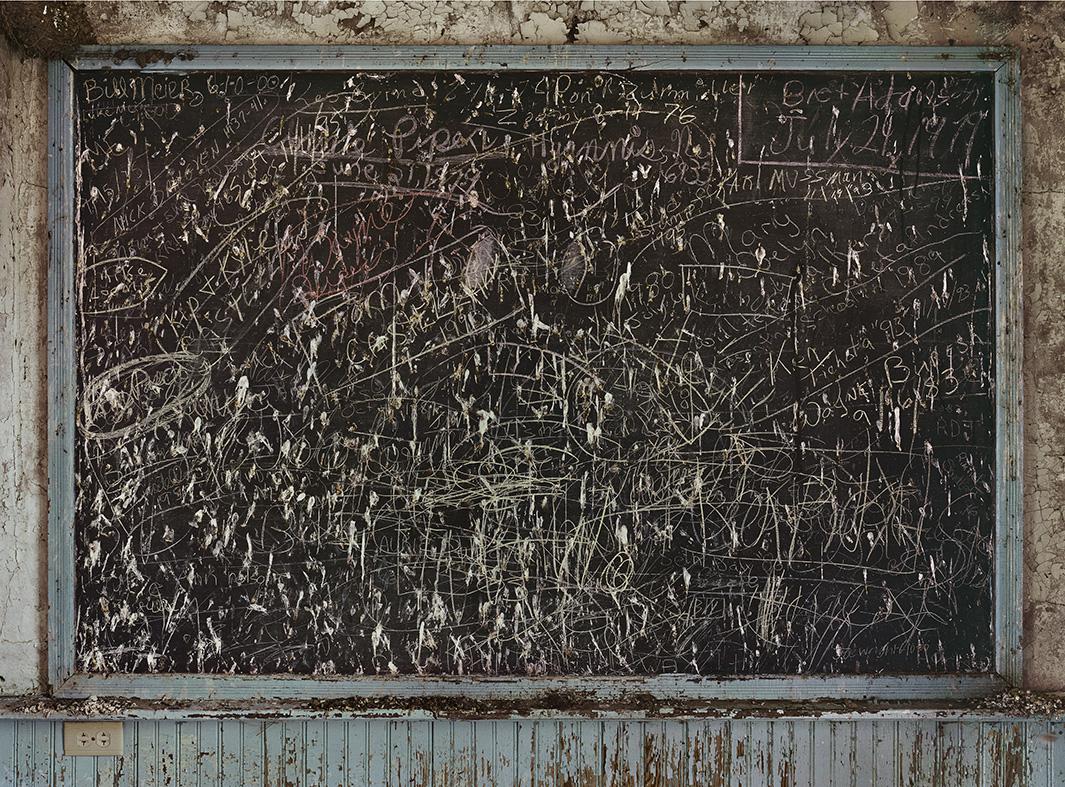

The photos in Dirt Meridian combine painterly landscapes as well as portraits on the ground of the resilient people who make their homes in these places. Some of Moore’s subjects read about his project in local newspapers and invited him to come visit them. In one case, he left a note in a mailbox at a New Mexico mansion he found interesting and eventually was able to make arrangements to photograph it. Many of the people Moore met are descendants of homesteaders who moved to the region during the late 19th century.

“They’re ‘no bullshit’ people. They’re solid, they’re individualistic, and they’re self-reliant. They’re also very genuine, very open, and ultimately very creative people. The landscape, with its openness and its emptiness, really inspires the imagination to fill in the blanks,” he said.

Copyright Andrew Moore

Copyright Andrew Moore

Copyright Andrew Moore

In 2012, Moore met a crop duster and the pair started traversing the landscape in a low-flying plane just dozens of feet off the ground, approximately at the level of a windmill. This unique perspective was both “infinite and intimate,” giving Moore enough proximity to picture things on a human scalebut enough distance to see them in a wider context.

“A lot of aerial photography shot from high up is a very abstract process; you’re creating patterns in the landscape. Here it was much more of a narrative approach,” he said.

Moore’s goal was to make images about emptiness without making them totally vacant. The trick, Moore found, was to focus on some small sign of human presence—an old house, for instance, or a farm—which could highlight the boundlessness of the space around it. In these cases, the land itself could tell the story of the place.

“There [are] no mountains in my book. It’s not a classical vision of the West. The region I was in was kind of flat and empty. It took a long time to find a way to shape that. You go out there and you have that experience of getting out of your car and you’re overwhelmed by stars and space—you’re alone and at the same time fully immersed in this open space. To translate that experience into pictures was the biggest challenge.”

Copyright Andrew Moore

Copyright Andrew Moore