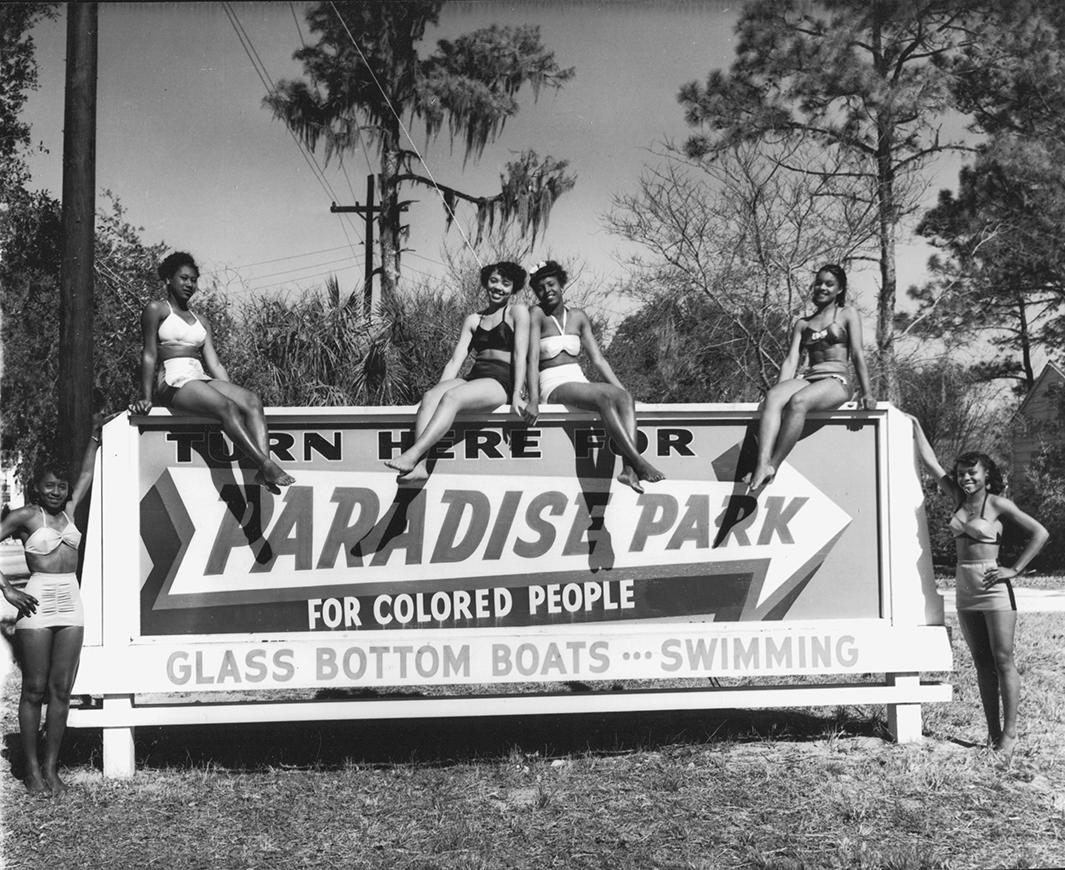

During the dark days of Jim Crow, Florida, which had a higher number of lynchings per capita than any other state, was one of the most dangerous places in America for black people. But it was also home to Paradise Park, one of the rare successful recreational facilities in the South exclusively for black Americans, which opened along the edge of the Silver River in 1949.

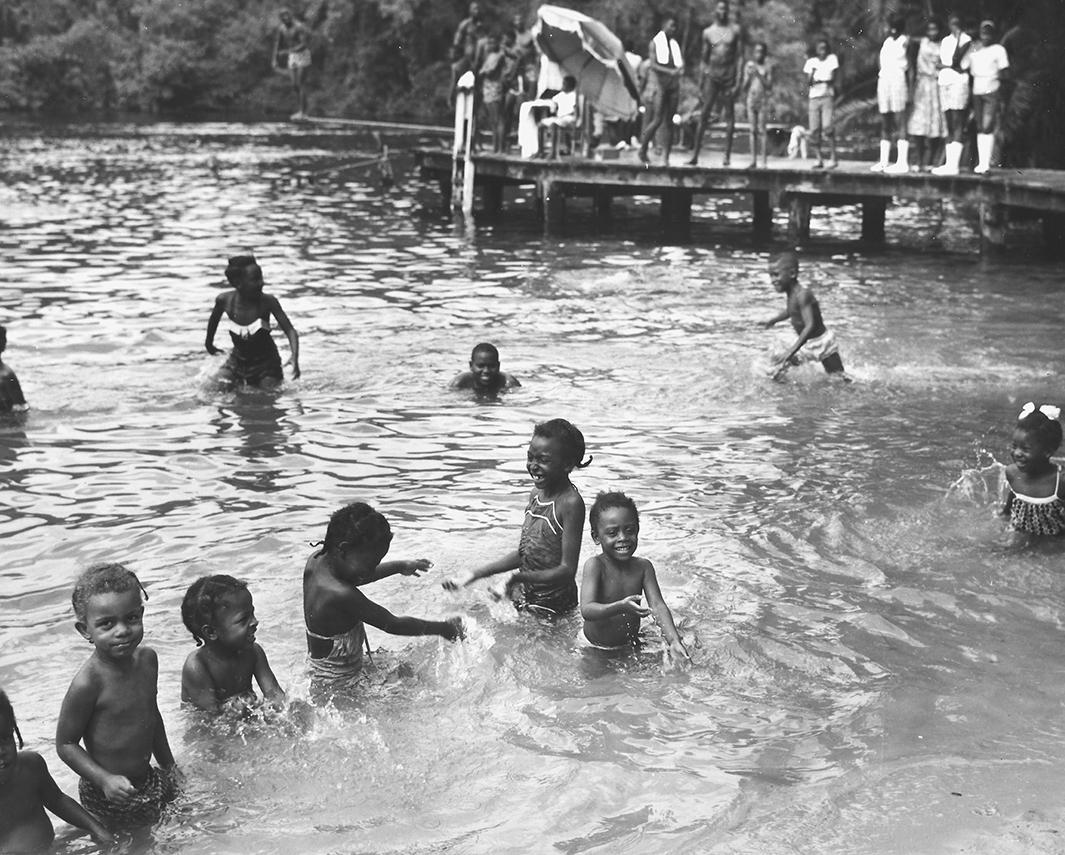

“Paradise Park was an oasis where [black] Americans could go with their families and relax, safe from the indignities and threats of violence perpetrated by whites. [Manager] Eddie Vereen ran the park like a peaceable kingdom where all were made to feel welcome. Even the alligators left people alone,” said Lu Vickers via email. Vickers, with Cynthia Wilson-Graham, wrote Remembering Paradise Park, which University Press of Florida published this month.

Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Courtesy of the Marion County Black Archives. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.

Photo by Addison Scurlock. By permission of the Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.

Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.

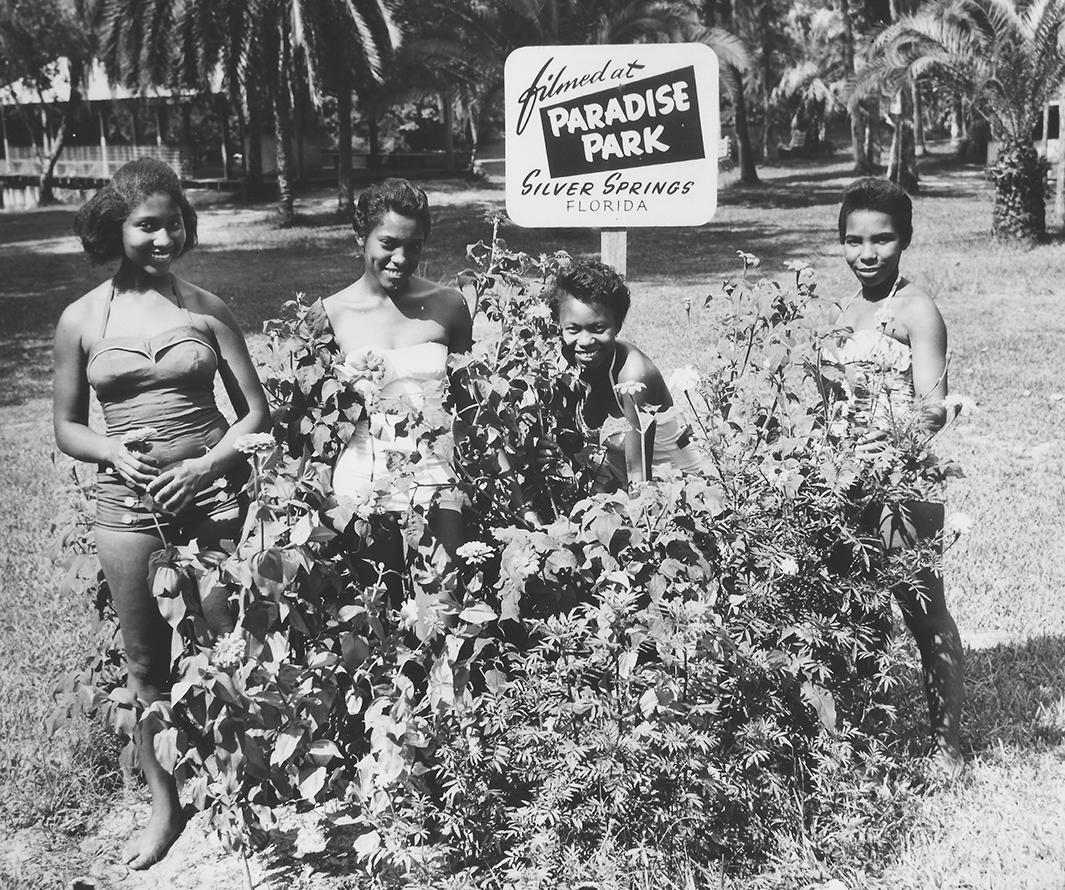

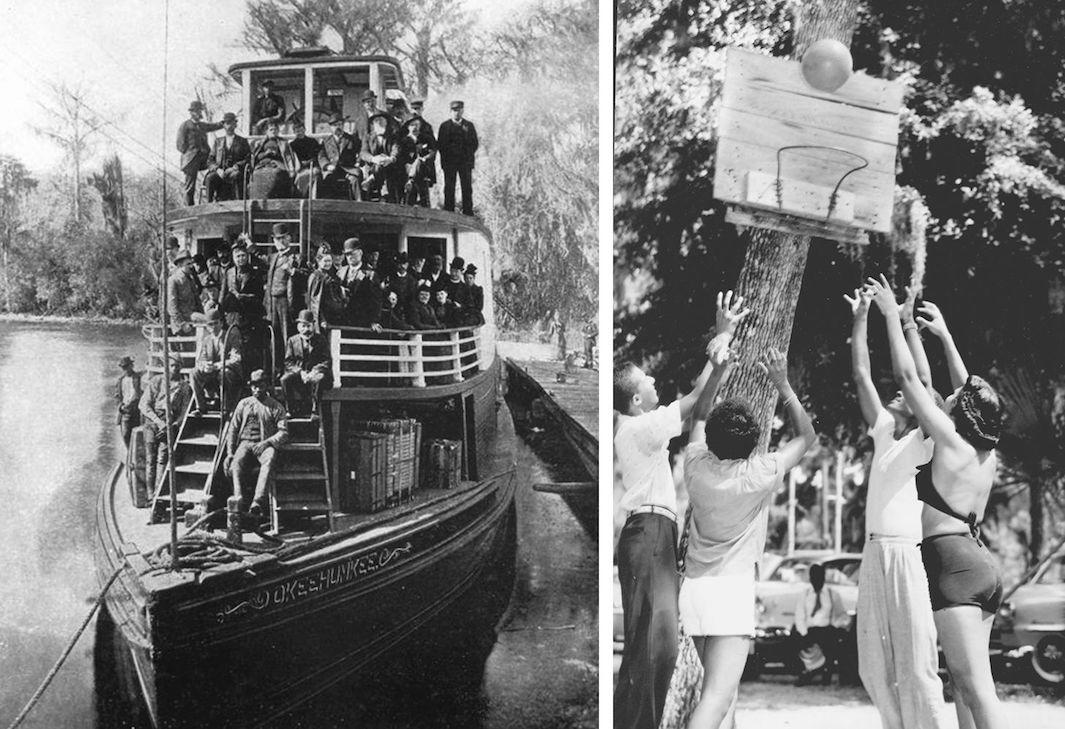

Paradise Park, a separate division of the adjacent tourist destination for whites, Silver Springs, had white-sand beaches and clear water, lush grass, glass-bottom boat rides, a soda fountain, and a reptile exhibit. Bruce Mozert, who was the official photographer at Silver Springs for decades, was the only professional photographer given permission by the owners of the two facilities, Carl Ray and Shorty Davidson, to take photos at Paradise Park. Almost all of the Paradise Park photos in the book come from Mozert, who is now 98. Others come from visitors or employees of the park.

Vereen was a tireless promoter of the park. He traveled around the southeast with a big “Paradise Park” sign attached to the top of his car and sent letters about the place to church associations and schools. As a result of his efforts, Paradise Park attracted black Americans from all over the country. Though Silver Springs and Paradise Park shared the same river, visitors to the respective segregated facilities rarely interacted.

“Reginald Lewis, the grandson of manager Eddie Vereen, told me one of his jobs was to keep white people out, but occasionally a white person would sneak in. Once found out, they were asked to leave. The irony of course is that Silver Springs only employed African-American boat drivers, so they drove boats for both white and African-Americans. Both parks shared the same boats and boat captains, and African-Americans could make the trip up to the headsprings but weren’t allowed to go onto the grounds,” Vickers said.

Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Courtesy of Marion County Black Archives. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.

Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Courtesy of Cynthia Wilson-Graham.

Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Courtesy of Marion County Black Archives. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.

Vereen retired as manager of Paradise Park in 1967. The park closed unceremoniously in 1969, and like many other facilities made for black Americans at the time, the buildings were bulldozed during desegregation.

“Many people felt that Paradise Park should have been saved, and lamented the fact that the community had no say in what happened to it. What happened after it closed was sad too: It was erased from history. But you cannot erase people’s experiences or memories. As Cynthia and I talked to people, hearing their stories and sharing in their laughter, Paradise Park came alive again.”

Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Courtesy of the Marion County Black Archives. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.

Left: By permission of the State Archives of Florida. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida. Right: Photo by Bruce Mozert. By permission of Bruce Mozert. Courtesy of Cynthia Wilson-Graham. Reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.