Since the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, photographers have been there to capture images of nuclear blasts. And whether they have been scientists working for governments, photojournalists on assignment, or artists responding on their own terms, their images have helped shape the way people have perceived the Atomic Age. The exhibition “Camera Atomica,” which is on display at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Canada until Nov. 15, explores that impact through more than 200 images from 1945 to 2012.

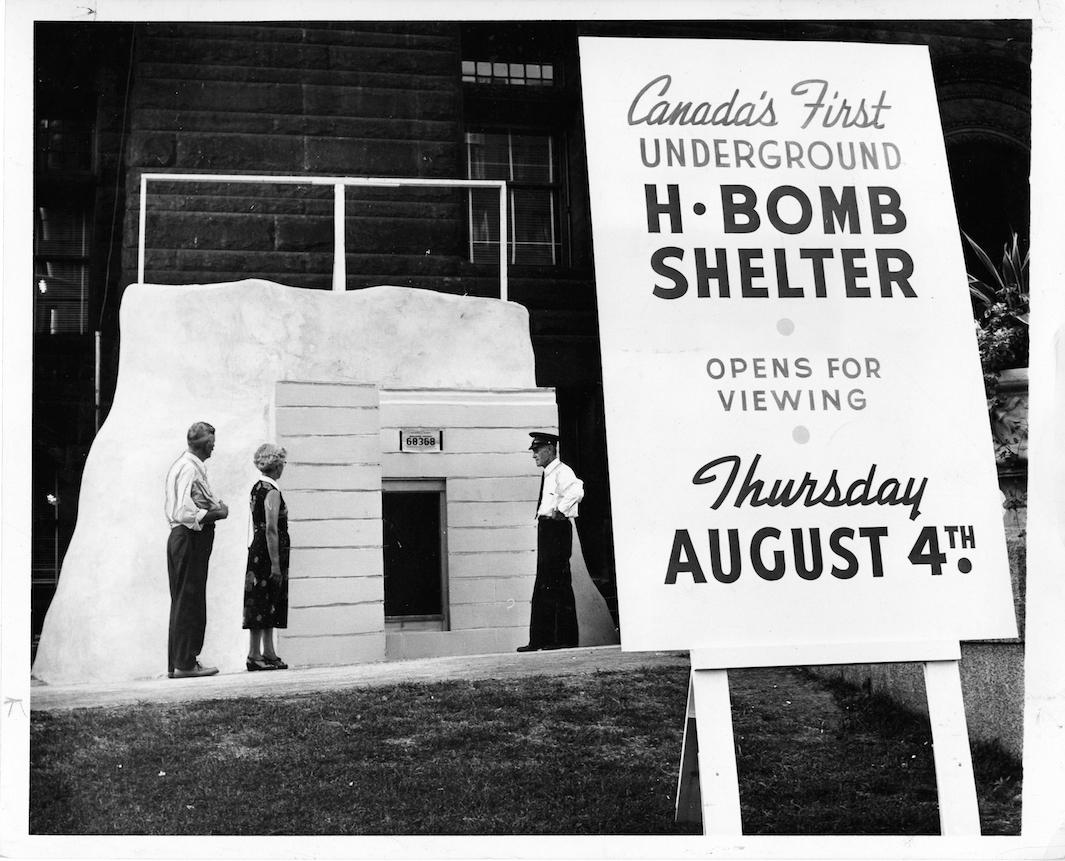

York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds

Copyright 2003 100 SUNS/Michael Light

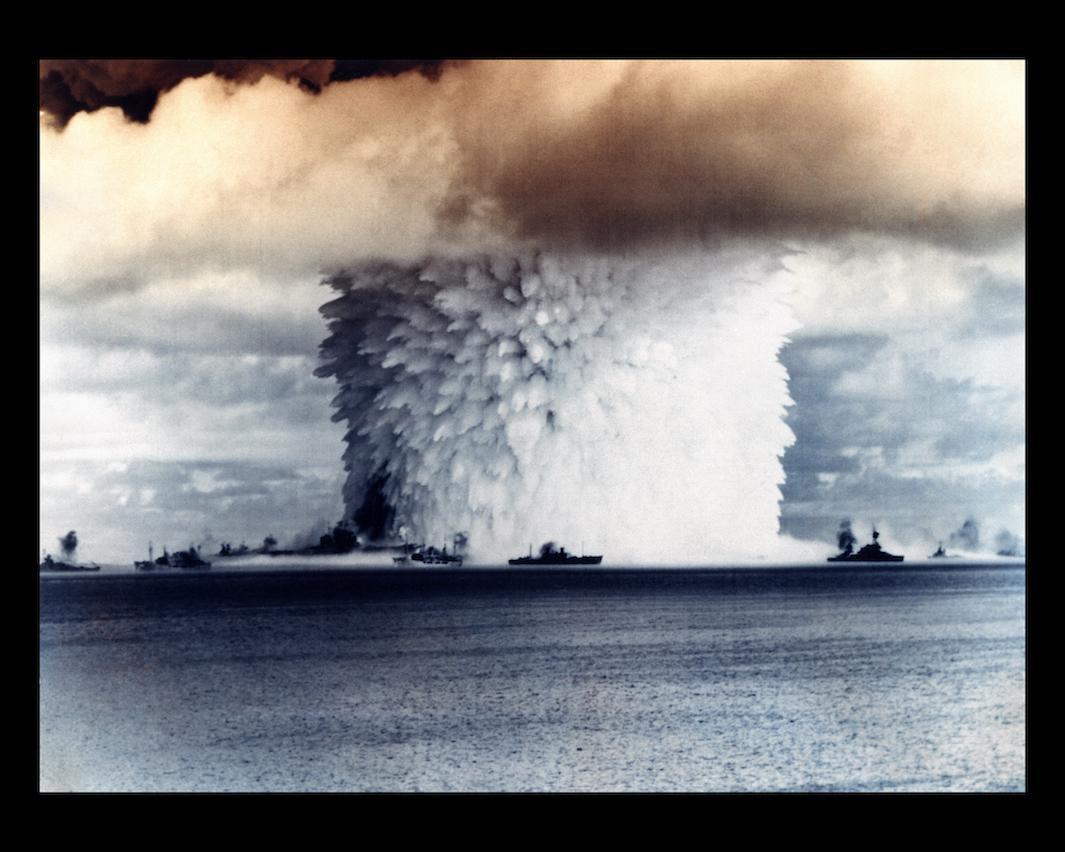

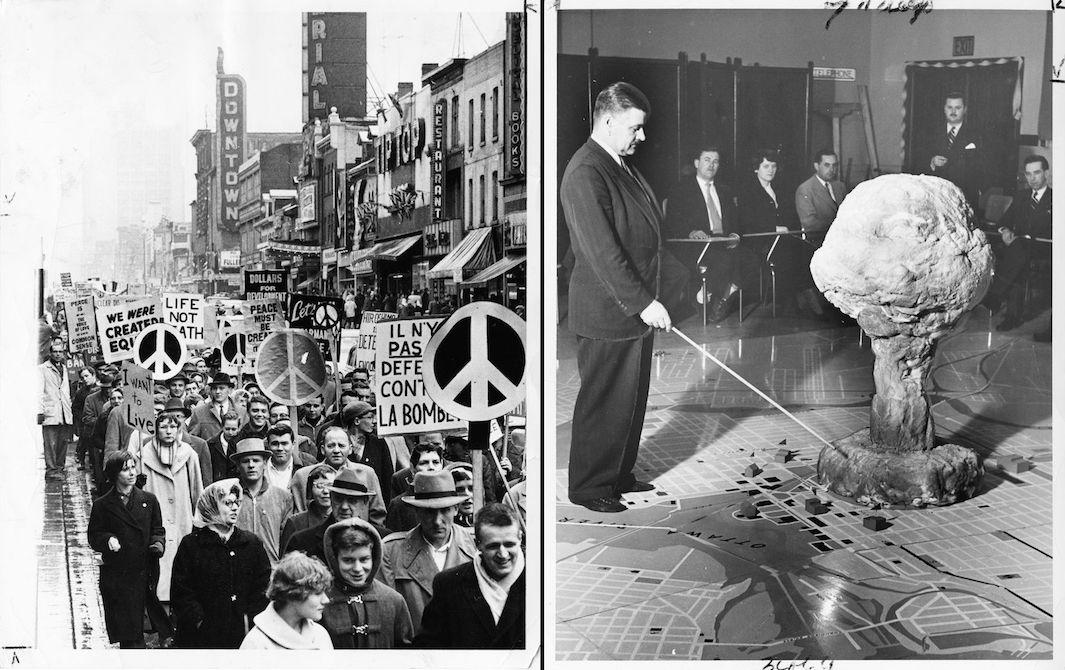

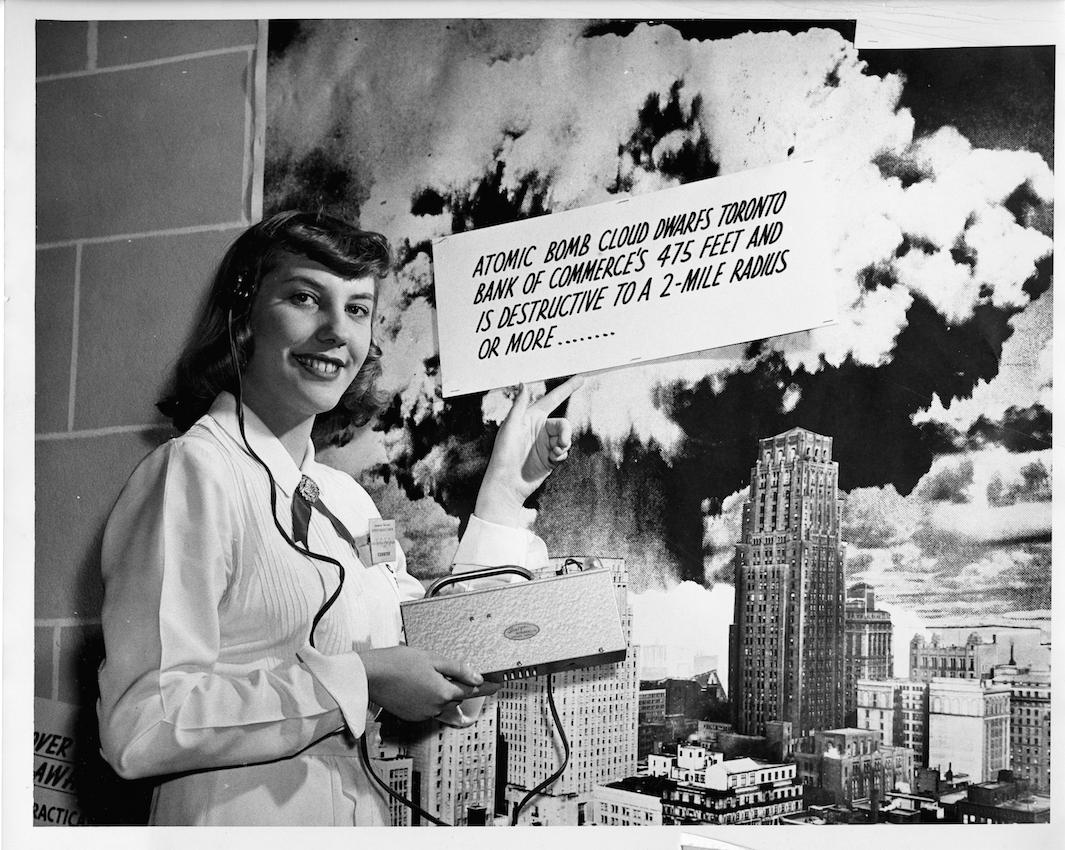

Nuclear power has always been a divisive issue, and images have been fueling debates from the very beginning. In 1946, the government used nuclear bomb tests like Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll to help influence public opinion. According to John O’Brian, who curated the exhibit, 750 cameras were present at the event, which was designed to “dispel reports about the dangers of radiation.” Berlyn Brixner, who was the head photographer at the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, Trinity, in July 1945, and Harold Edgerton took photographs for the U.S. military. Ultimately, the visuals they provided were intended to help build better bombs.

“When the photos were no longer a matter of top-security, they were released for circulation by the media and others and helped to construct an image of the bomb as the nuclear sublime. Eventually, they came to be seen as aesthetic achievements. Every part of the globe has been stamped with the photographic spectacle of the mushroom cloud, which is the dominant icon of the Atomic Age,” O’Brian said via email.

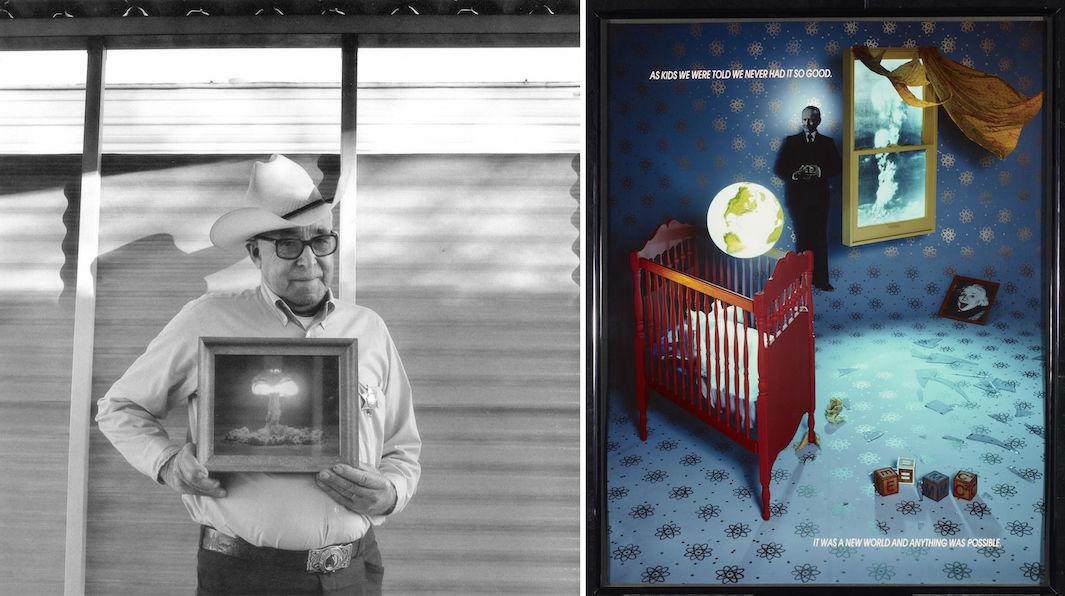

During the 1980s, many photographers responded to the escalating risk of nuclear confrontation by taking an active stance against proliferation. In 1987, Robert Del Tredici along with Carole Gallagher founded the Atomic Photographers Guild, which archives images of the people and places impacted by nuclear weapons and energy. The goal, according to Del Tredici, is “to get people to realize that nuclear weapons are not only symbols, though they are almost exclusively discussed as if they were symbols.”

Other artists, like Sandy Skoglund, responded to the atomic age with more abstract imagery that addressed the dangers of nuclear energy and weaponry. In her photograph Radioactive Cats, dozens of sculpted plaster cats are covered with Day-Glo paint. Its dark humor made it an icon of the atomic age and the Cold War.

York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds

York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, copyright 1980 Sandy Skoglund

When it comes to the most famous nuclear event in history, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the type of photography that emerged depended on who was producing it. Yoshito Matsushige photographed Hiroshima just hours after the blast and Yosuke Yamahata photographed Nagasaki on Aug. 10, the day after “Fat Man” was dropped. Their photographs are the work of direct witnesses to what happened to their respective cities. Americans, meanwhile, first photographed the cities from the air at the time of the bombing, producing the first images ever circulated of a mushroom cloud.

“American military photographers in the air were engaged in acts of documentation rather than of witnessing, and that was also the case of the photos taken on the ground following the end of the war, when American photographers entered the cities,” O’Brian said.

While nuclear blasts have often been well-documented, O’Brian said, relatively few government images circulate of the extensive preparations leading up to a detonation or the aftermath on the ground once the clouds have dispersed.

“Like photographs of flag-draped coffins of American soldiers returning from zones of conflict, they have been edited out of visibility by censors.”

Copyright David McMillan

Left: Copyright Carole Gallagher. Right: Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift from The Peggy Lownsbrough Fund, 1986. Copyright Carol Condé and Karl Beveridge/ CARCC.