Stephen Voss was a student at the George Washington University when he first encountered bonsai trees nearly 20 years ago at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum in Washington, D.C.

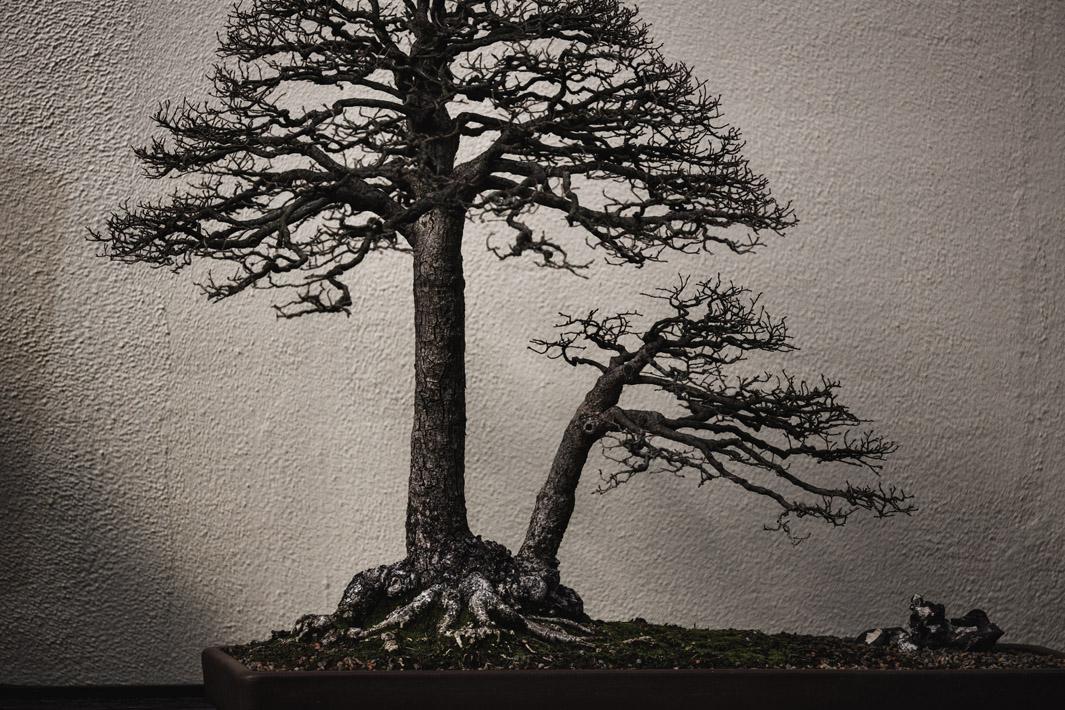

“Initially, I was just amazed that a living thing could exist in this state—so small and sculpted, and for so many years,” Voss said via email.

Over the years, Voss habitually visited the old trees and learned more about the ancient Japanese art form behind them. But he never felt compelled to photograph the museum’s amazing collection, which is considered one of the best in the world outside of Japan, until a year ago.

“It was sort of a respite from my professional work. I primarily am a portrait photographer and my portrait shoots are usually pretty quick, without a lot of time to really make a connection or earn trust with my subject. This work can be thrilling and I always love the challenge of it, but I also felt like I was losing touch with some of the things I loved most about making photographs. Bonsai trees were a silent, unmoving subject, and photographing them was a meditative exercise free of any distractions,” he said.

Stephen Voss

Stephen Voss

Stephen Voss

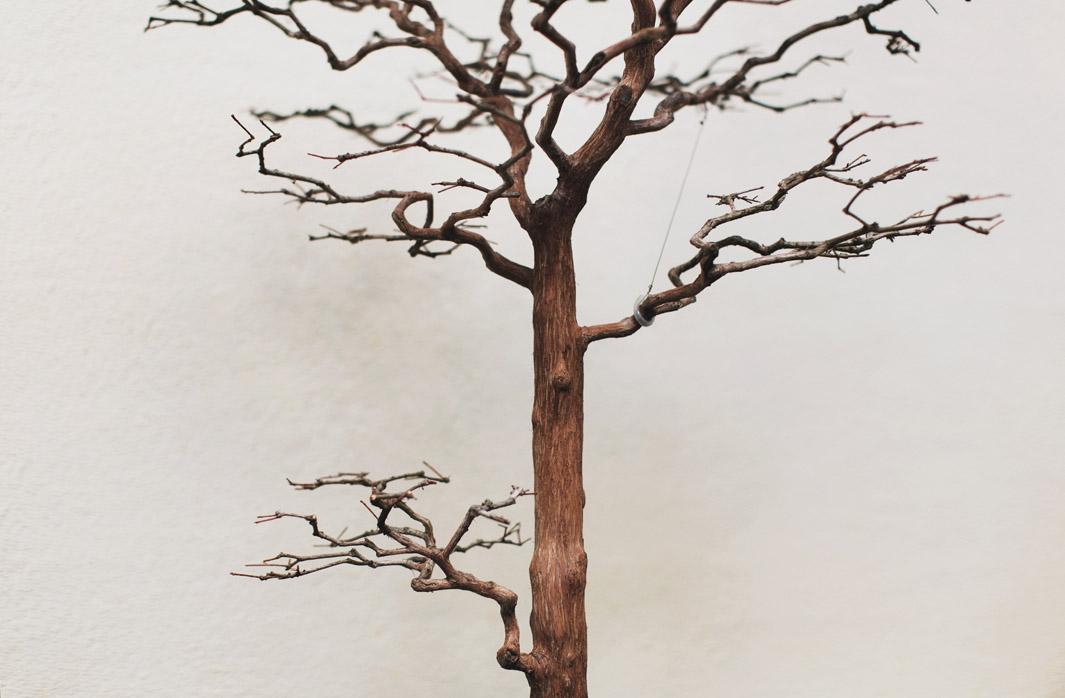

Voss is now raising money on Kickstarter to publish a book, In Training, which includes the nearly 50 trees he photographed over the past year. The trees in the museum’s collection are from China, Japan, and North America. The oldest tree in its Japanese collection is a 1625 Japanese white pine, which miraculously survived the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima.

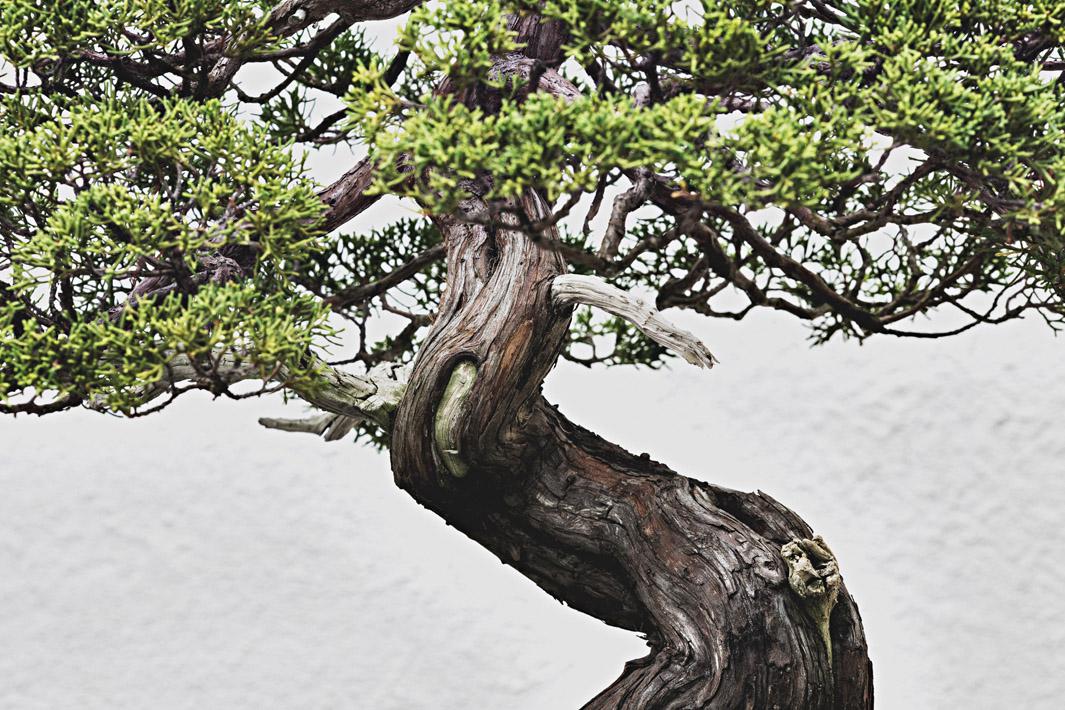

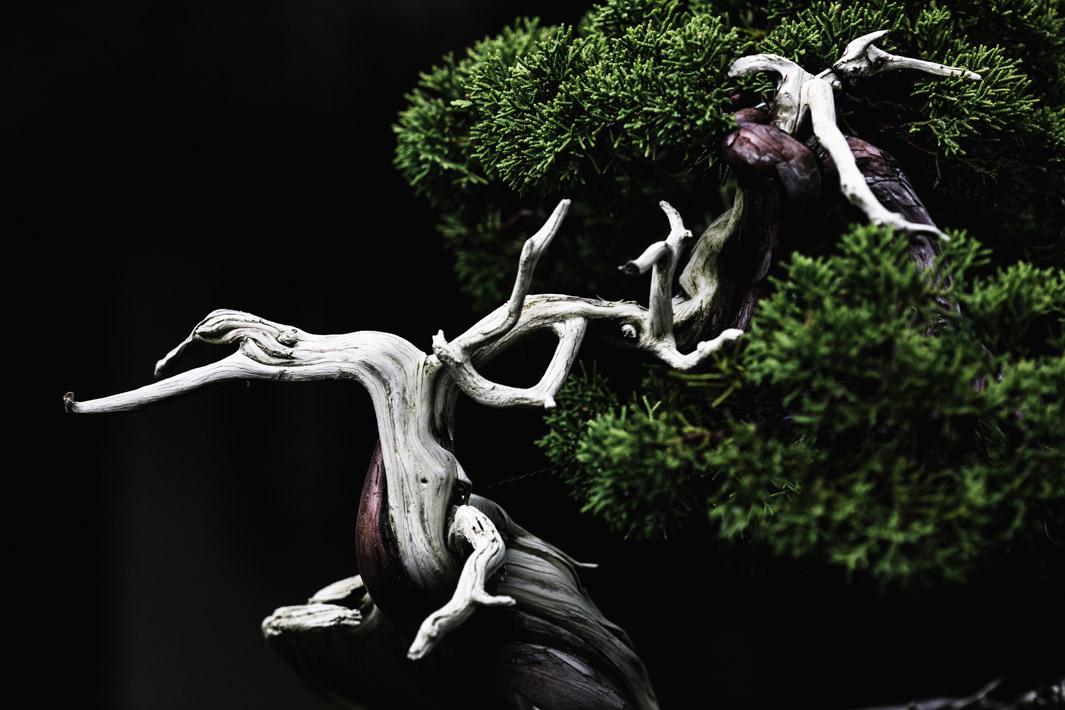

Voss shot the trees using natural light, which meant he had to wait for cloudy, overcast days to get the kind of color tones he wanted. Because of the way the trees are displayed at the museum, he was only able to photograph them from the front, which made his options for composition somewhat limited. But Voss found those constraints actually allowed for more creativity. Rather than shoot the entire tree straight on, like much of traditional bonsai photography, he frequently focused on a small section of the tree.

“I do my best to let the photos develop organically from what I see in each tree, rather than trying to fit a predefined aesthetic. If I were to define it more, I am pretty obsessed with form and shape and do try to look for some level of abstraction in these trees, rather than just making a visual record of each one,” he said.

Stephen Voss

Stephen Voss

Stephen Voss

Voss wants his photos to convey the beauty of the trees and the sense of peace and hope he felt when he was around them. But while Voss is certainly a great admirer of bonsai, and great at photographing them, he says he’s not cut out to be a bonsai master.

“I don’t currently have any bonsai. I realized after trying to keep mine alive through the hot summers in D.C. that photography was the best way for me to show my appreciation for this art form.”

Stephen Voss

Stephen Voss

Stephen Voss