Stephen Kelly moved to Myanmar in 2013 to document the country’s political and economic transformation after decades of military rule. He would often ride his bicycle down Yangon’s Bogyoke Aung San Street past the Waziya Cinema and stop to take a look. As he learned more about the theater, he saw how changes in the Myanmarese film industry reflected changes in the country.

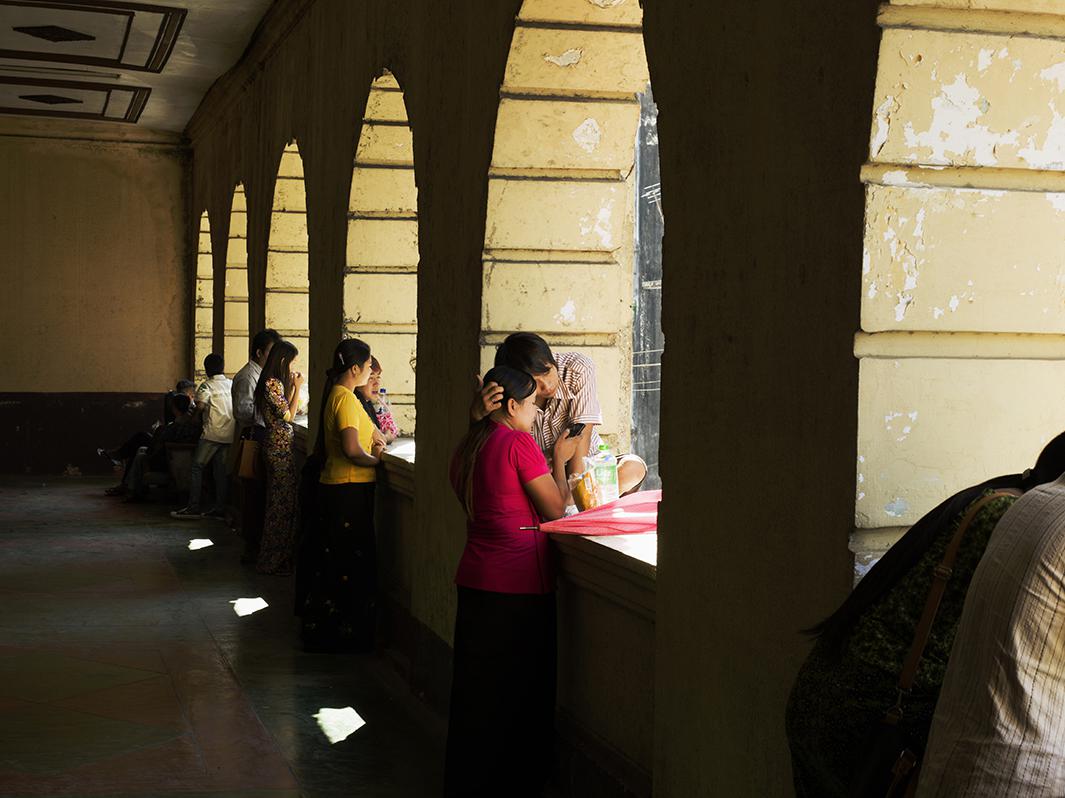

The Waziya is a rarity in the historic Myanmarese neighborhood—it’s the only remaining cinema on a strip once known as “Cinema Row.” In an attempt to modernize, the five other pre–World War II theaters that once lined the street have been replaced with high rises, shopping malls, condominiums, and hotels.

Stephen Kelly

Stephen Kelly

During the first half of the 20th century, the film industry in Myanmar was one of the most successful and prolific in the region, and there were more than 300 theaters showing local films. When the government took control in 1968, the number of theaters sharply declined, and the quality of films suffered.

“What interests me about the industry is that it has a long, rich, varied, but also a troubled history, with all the tumultuous political and social changes that have taken place. It is a film history that not many people today are aware of and once I began to research more about it, I became immediately fascinated by it. I felt that by documenting a fragment of this heritage, I would somehow be able to open a small window into the world of this once great and vibrant industry,” he said via email.

Stephen Kelly

Stephen Kelly

Stephen Kelly

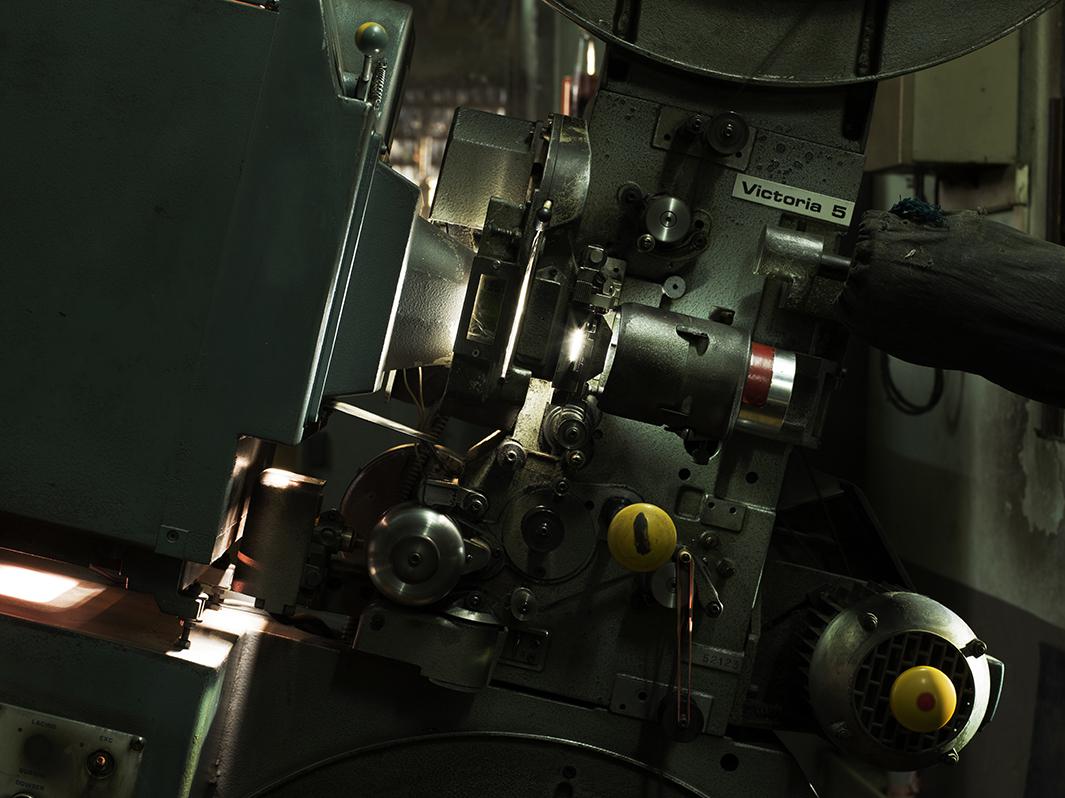

Kelly visited the Waziya almost every day from October 2014 to February 2015 for his series, “As the Lights Fade I.” Sometimes he’d stay for one or two hours; sometimes he’d stay all day. There were four screenings daily—horror, dramas, and comedy films were the most common—and the most popular were the first two of the day. On most days the theater was relatively quiet and he could wait for hours without making a photo. He spent most of his time in the hot and dusty projection room with a small team of projectionists, drinking coffee and watching films.

The Waziya temporarily shut its doors this year after the lease on the building expired. Currently, the Myanmar Motion Picture Association and the Yangon Heritage Trust are working to turn it into a modern cinema and performing arts space. As the country moves further from its authoritarian past, Kelly thinks the industry can recover and the Waziya will thrive once again.

“There seems to be hope for the future, as censorship has eased and the ability to express oneself more freely is returning to a certain extent. A sense of being cut off from the outside world is also diminishing and access to the Internet is proving to be pivotal in influencing and inspiring the next generation of Burmese filmmakers.”*

Correction, Aug. 21, 2015: This post originally misquoted Stephen Kelly as saying “Myanmarian filmmakers.” He referred to the filmmakers as “Burmese.”

Stephen Kelly

Stephen Kelly