Flo Razowsky was working with grass-roots communities in the Palestinian territories in 2002 when she saw construction begin on what is now the nearly 500-mile-long Israeli West Bank barrier.

“My first thoughts were of complicity: As a Jew, this wall was being built in my name; as a U.S. citizen, this wall was being built with my tax dollars,” she said via email. “My first thoughts were of wondering how prolific such situations were—firstly, nation-state barriers that were being built to keep people out and increasingly, the more research I did, barriers that were being crossed at risk of death in order to maintain survival.”

Flo Razowsky

Flo Razowsky

Flo Razowsky

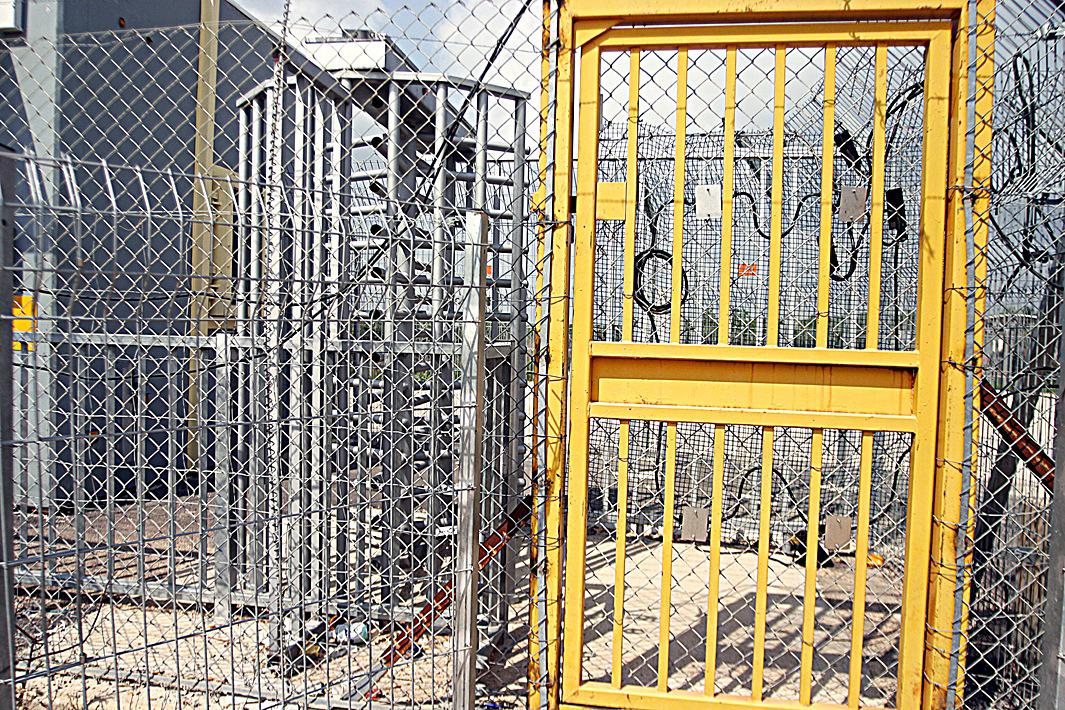

Razowsky’s inquiries led to her ongoing series, “Up Against the Wall,” which comprises photographs of “borders built by so-called first-world nations as they bump up against so-called third-world ones.” She spent roughly six months a year between 2002 and 2008 in the Palestinian territories and has also visited the border between Ukraine and Slovakia, Serbia and Croatia, Mexico and the United States, and Morocco and the Spanish city of Melilla.

“I think considering the actual structures allows us to consider the global connections of power—why these structures exist, who builds them, to what ends, and who is impacted by them,” she said. “Being able to visualize these structures offers those of us who aren’t forced to deal with them another piece of the reality faced by those attempting migration.”

Her photographs are wide landscapes of seemingly endless snaking walls and detailed close-ups of chain link, steel, and concrete; occasionally they show the stone-faced guards charged with guarding the borders or the migrants who are stopped at them. While the borders may look different from one another, Razowsky wants the series to draw connections between these structures and the policies they help uphold.

Flo Razowsky

Flo Razowsky

Flo Razowsky

“No matter the location in the world or the specific population these structures impact, they are all part of maintaining the current world of increasing free trade and globalization—a world that forces people to leave their homes in search of livelihood yet criminalizes them for doing so,” she said.

Getting these photos in highly policed areas is often a challenge. She never asks permission from authorities to photograph a location, so stealth and shooting from the hip is often necessary to avoid being harassed. For the most part, she’s gotten away unscathed. “I’ve had to talk my way out of detainment and have largely been able to avoid erasing my memory card even if ordered to do so. Some of my best shots have come from both of those types of situations,” she said.

In 2011, at an exhibit of his work in Minneapolis, Razowsky asked social justice organizations to present material to viewers about their work. Her goal, she said, is for the series to motivate people to get involved in organizations that fight some of the injustices she has documented.

“I believe that art has the power to move people to act. ‘Up Against the Wall’ becomes a tool in that toolbox exposing those of us not forced up against the walls in this world to face the reality created to protect and uphold our privileges. Once we are exposed to the realities we are not forced to endure yet exist for our benefit, I believe and hope it becomes harder to ignore and allow those realities to flourish.”

Flo Razowsky

Flo Razowsky

Flo Razowsky

Correction, Aug. 8, 2015: This post originally misidentified Flo Razowsky as a man. She is a woman.