This post contains nudity.

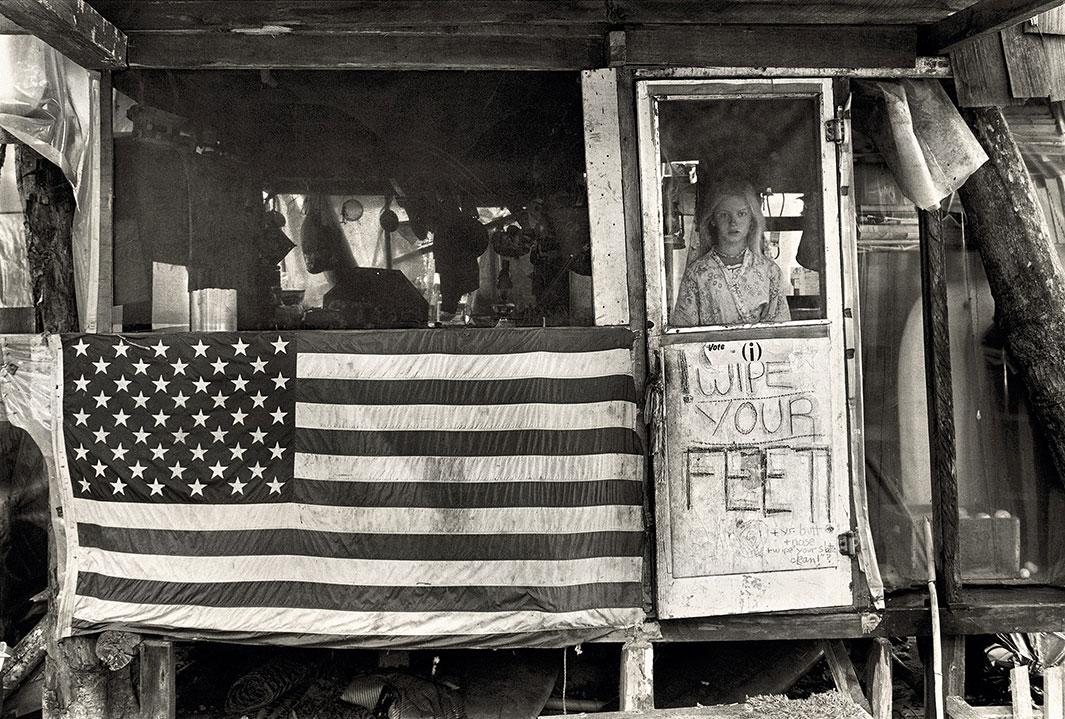

What separates Taylor Camp—John Wehrheim’s photographs of the alternative community started by Elizabeth Taylor’s brother in 1969—from a typical yearbook are the interviews. Conducted 30 years after the camp was burned down in 1977 and the government condemned it to make a state park, the interviews with members are informative—explaining how people ended up at Taylor Camp—and indicative of the time—delving into how the political climate on the mainland affected their small community. They give a voice to a “hippie culture” that is often stigmatized while providing a glimpse into the seemingly mythological history of Taylor Camp.

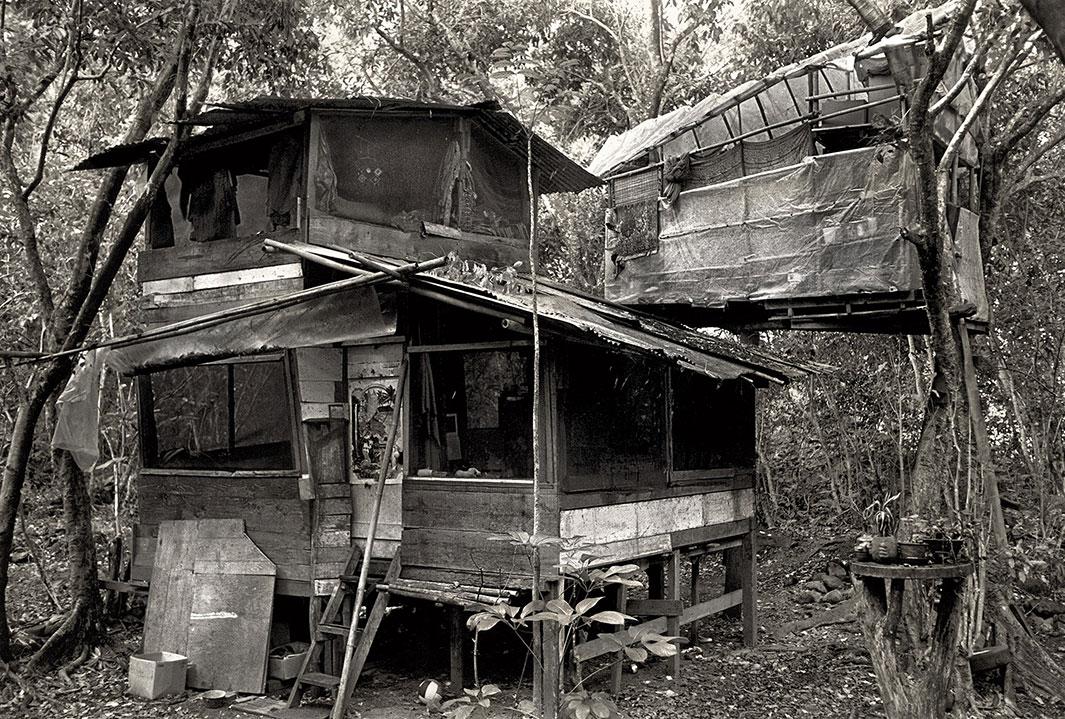

In 1969 Howard Taylor owned seven acres on Kauai’s North Shore and invited a group of young men, women, and children who had recently been arrested for vagrancy—the 13 original colonists, so to speak—to set up camp there.

Although none of the first 13 lasted the year, new settlers visited and established residency by building treehouses and forming a self-sufficient community of unwritten laws with a mayor, a sheriff, a food co-op, a public water system, and a number of churches. “But Taylor Camp wasn’t a commune,” Wehrheim writes in the introduction. “It had no guru, no clearly defined leadership, and never had a single voice. It had no written ordinances. It wasn’t a democracy. It was much more than that: a community guided by a spirit that created order without rules.”

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

Wehrheim never lived at Taylor Camp, but in 1971, during a visit to the camp, he began to photograph it, returning again a few years later to complete a thorough catalog of images that would become part of Taylor Camp. (He also created a documentary of the same name.) Wehrheim said when he first arrived with two cameras, a bag of lenses, and a tri-pod, everyone disappeared except Debi Green and her sister Teri. When Wehrheim returned a week later with some 8-by-10 selenium-toned archival silver prints for the sisters, suddenly everyone wanted to be photographed.

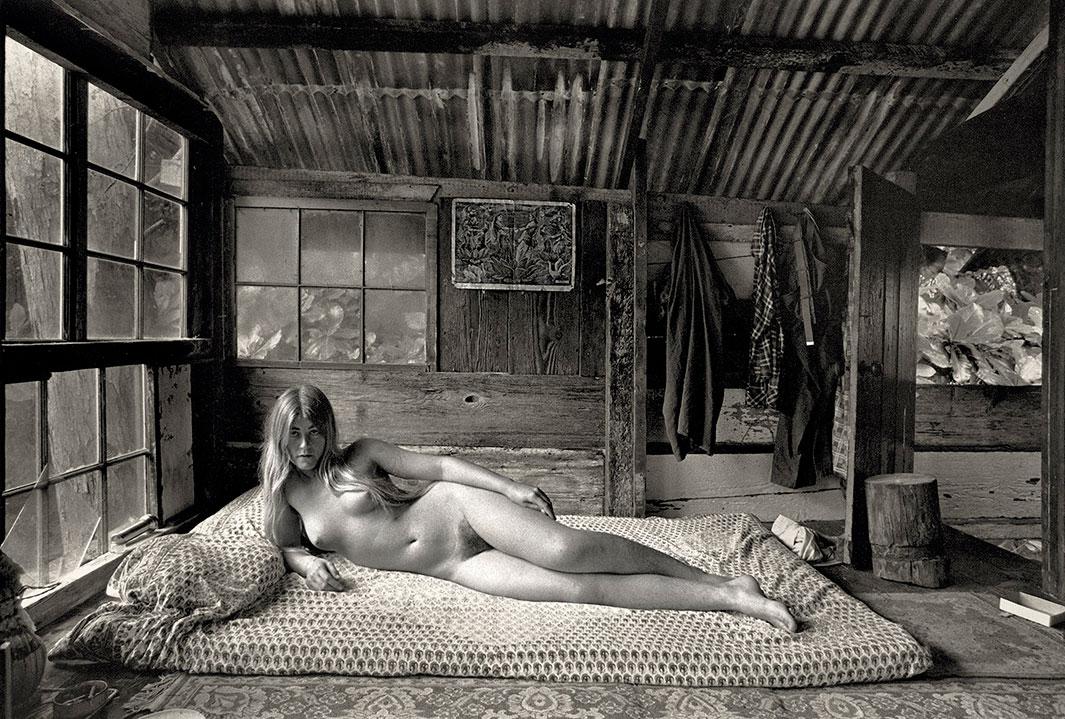

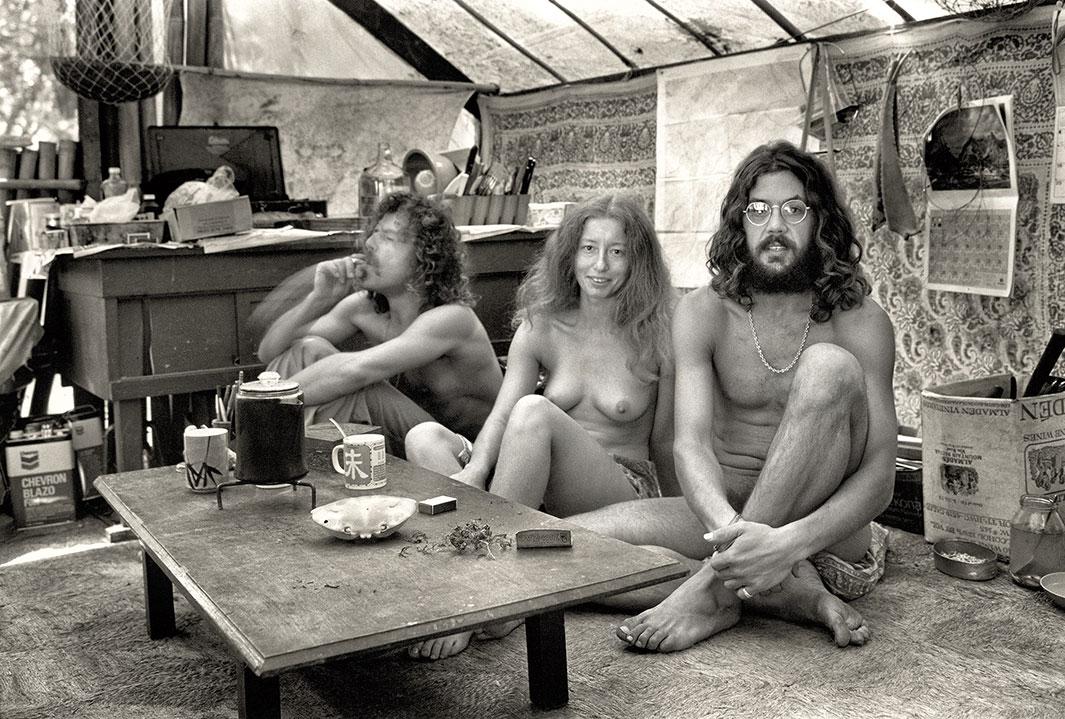

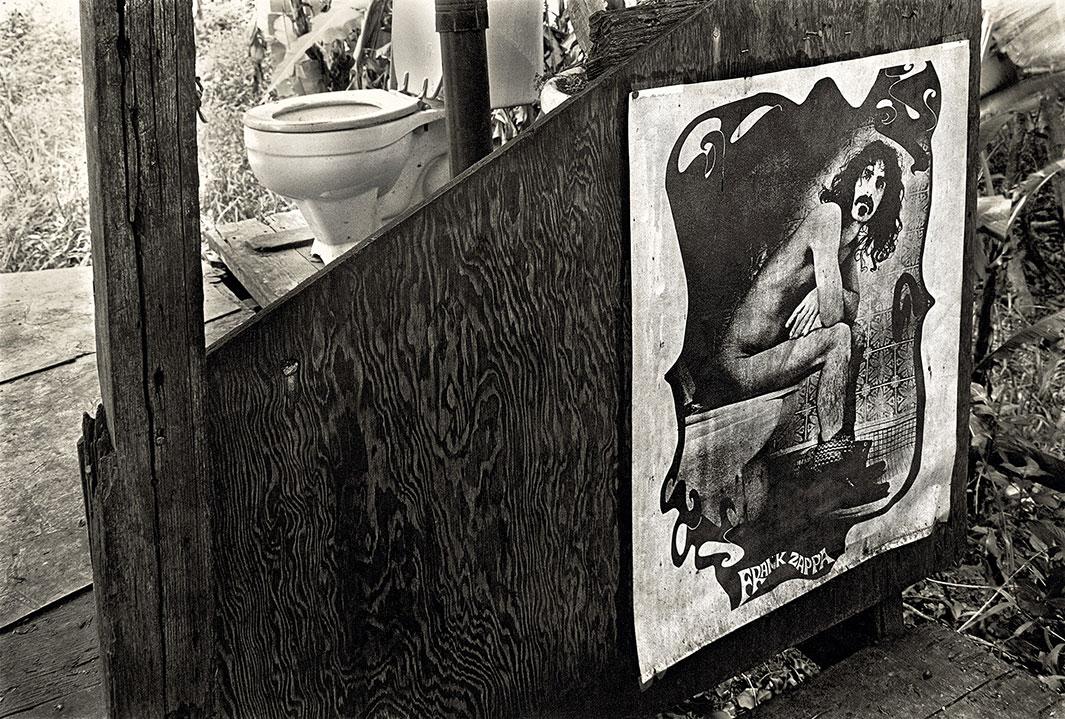

“In a few weeks I was keeping an appointment book, bribed with dinner invitations, great pot, wonderful parties, and inviting beds,” Wehrheim wrote via email. “I’d made portraits of everyone that wanted to sit for me and then became a fly on the wall. My subject was really the campers, not the camp: young, beautiful people, healthy, in great shape, often naked; many accomplished college athletes and big wave surfers.”

It also didn’t hurt that many of his subjects were in a “relaxed” state of mind when being photographed, so Wehrheim never felt rushed.

“If I thought that they weren’t relaxed and open I fumbled around until they were no longer self-conscious and became bored. I often told the campers that they had to hold still when the shutter speed really didn’t demand it just to get them in to a meditative frame of mind.”

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

Through the publication of the book and film, Wehrheim is giving a voice to the people of the baby boomer generation who were living within a dynamic new culture but one that was far from single-minded.

“I tried not to romanticize Taylor Camp,” Wehrheim wrote. “Anyone who reads the book or looks at the film will find a story that includes addiction, disease, alcoholism, violence, and sexual abuse: the same things that one finds in any community.”

Recently, coverage in various online publications, including Featureshoot, once again placed Taylor Camp back in the news, something Wehrheim said happens every few years.

“Taylor Camp has a life of its own,” he said. Creating the book and film about it is Wehrheim’s way of keeping that spirit alive.

“Thirty years later when we tracked down and interviewed many of the campers, most—but not all, were nostalgic, recalling their time at the camp as the best days of our lives. But I think that may be true for many Americans of the boomer generation. We remember the ’60s and ’70s as a period of excitement, radical change, hope, and possibility. We were young and we were free because we possessed little but youth—and no student loan debt.”

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim

John Wehrheim