Since the beginning of the Magnum Photos cooperative agency, its elite photographers have been covering conflicts, including civil wars, around the world. But in the decades since its founding in 1947, the nature of warfare has changed, as has the nature of photojournalism. The exhibition “Failing Leviathan: Magnum Photographers and Civil War” which is on display at the National Civil War Centre in the U.K. until Nov. 5, shows those dual evolutions through the work of 11 photographers in 11 conflicts.

When Magnum co-founder Ropert Capa covered the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, journalists were invited by the warring parties to cover the action, said Julian Stallabrass, who curated the exhibit. Major outside powers were often involved in the fighting and the conflicts had their origins in ideological differences. Photographers covered either one side or the other. Today, Stallabrass said, civil wars tend to be “messy long-term multisided resource battles” between local forces.

Copyright Werner Bischof/Magnum Photos

Copyright Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Photographers, meanwhile, now occupy more ambiguous roles in the conflicts. “It’s not clear the photographers are not partisan supporters of any particular side,” Stallabrass said. The sort of gaggle of international press photographers that Werner Bischof captured during the Korean War in 1952 is uncommon; today, countries don’t invite journalists en masse to witness civil war. Moreover, far fewer publications send photographers to war zones; many photographers today work independently with no guarantee of being published and few personal protections. Magnum photographers are rare exceptions.

“The illustrated magazines were once a huge commercial force and the successful photographers within them were given immense resources in terms of time and money. Obviously the media as we know it now is nothing like that. Major newspapers are in financial trouble and have increasingly abandoned reporting from war zones. There’s an attraction to war photography, but at the same time it’s difficult and expensive. The market for these things is no longer clear either. That’s why they’ve been turning to Instagram or self-publishing,” Stallabrass said.

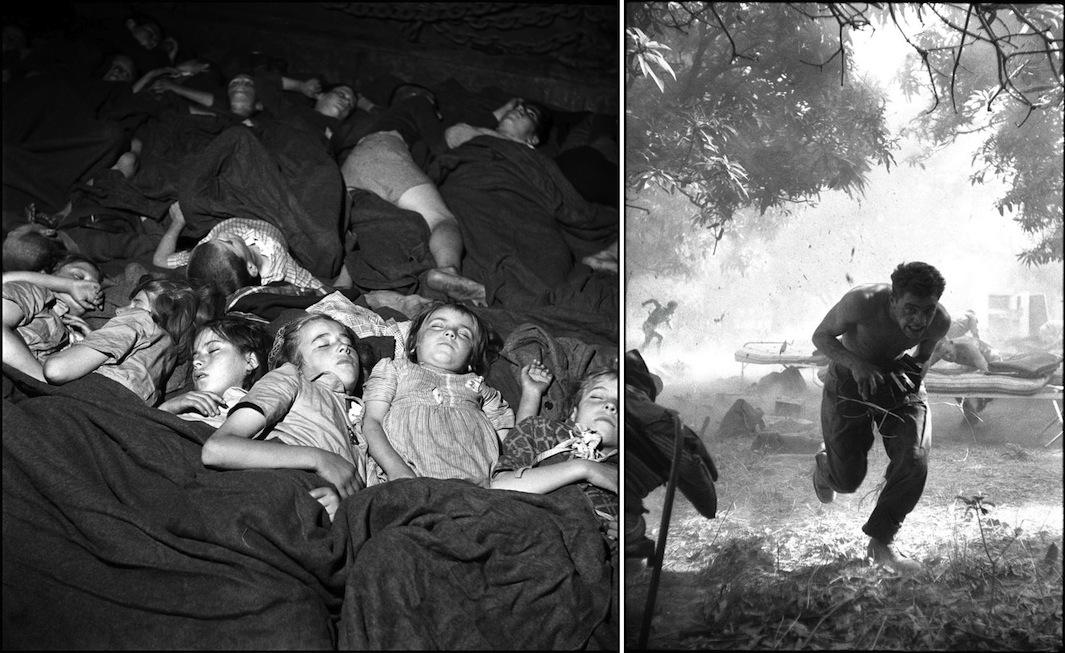

Left: David Seymour/Magnum Photos. Right: Copyright Ian Berry/Magnum Photos

Left: Copyright Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum Photos. Right: Copyright Robert Capa, copyright International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos.

Increasingly, people in war zones can tell their own stories with mobile cameras and social media. Still, Stallabrass said, Magnum photographers can tell stories in ways that amateurs can’t, and their services therefore may be more essential than they’ve ever been.

“It’s much easier than it used to be to take decent images, photos that are in focus and properly exposed even in tricky positions. But photographers can build a narrative into a picture to show what’s going on, to show competing or contradictory images within a single frame or across a series of pictures. That’s a real skill and it takes many years to develop it. That’s what amateurs lack.”

Copyright Tim Hetherington/Magnum Photos