A decade ago, Jo Farrell was having a hard time finding women in China with bound feet to photograph. Her driver overheard her frustrations and mentioned that he could arrange a meeting with his grandmother. Farrell traveled to a remote village in Shandong province where she met and interviewed the woman who, after consulting with her own son and daughter-in-law, decided to show Farrell her feet.

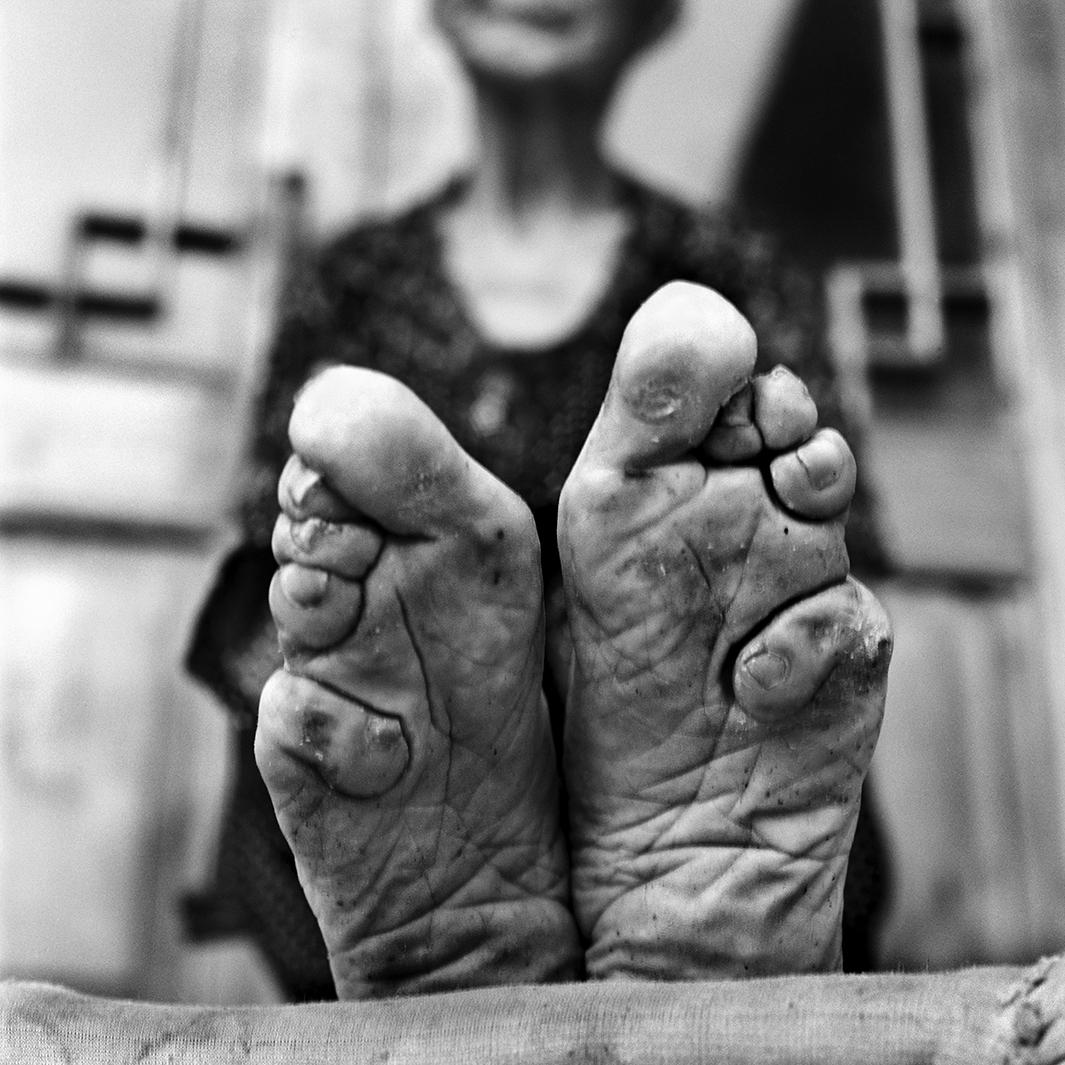

“Looking back on it, I am not sure what I was expecting,” Farrell wrote via email. “Such cruel and ugly words are used to describe bound feet. I held her naked foot in my hands and was surprised how soft to the touch her feet were. I was also taken aback because in some ways the form of her foot was quite beautiful. I think this also stems from a feeling of empathy that she had gone to such extreme lengths to be considered beautiful, desirable, marriage potential. It really resonated with me and I became even more excited about the project and eager to find more women to tell their stories.”

Since then, Farrell has traveled around China, meeting, interviewing, and photographing women whose feet were bound, often finding her subjects through word of mouth. At first, Farrell wrote that the series was about finding the women; after working for so long with them, she now says she has become much more emotional about what they’ve been through.

Jo Farrell

Jo Farrell

Jo Farrell

“Most people’s immediate reaction is how bad this custom was,” she wrote. “I now see it as more of a means to an end. In their society it was the only way forward for women: It would garner them a better future, a better life; in their society it was considered beautiful and then later on it was considered backward. Can you imagine first of all being praised for going to such extreme measures and the torture you went through to be aesthetically pleasing only to be demonized as an adult for complying with standard practices?”

Farrell chose to document the series with black and white film. As a child, she loved film noir because “through light, shadow, and form [it] depicted moods and ambience.” She also believes that film photography is a fine art since there are only 12 frames per roll which means every shot counts; she doesn’t crop the images she prints herself saying what the viewer sees is what she intends to photograph.

Jo Farrell

Jo Farrell

Although Farrell published a book in 2006 that includes a bit of the series and another one in January called Living History: Bound Feet Women of China, she hopes to publish a coffee-table book of the work as well as exhibit it in a gallery.

“I came into this project with preconceptions like most people have, that this was a custom only done by the elite who lived lives of luxury in beautifully embroidered shoes, only to discover that this tradition transcended different classes just like any fashion statement. The women in my project all come from rural areas and are typically peasant farmers who have lived through some of the harshest times in China. I have learned so much from hearing their stories and being part of their lives. As a photographer, I am a storyteller and I hope people can have a better understanding of this tradition through looking at my work. It has been an honor to have been part of their lives.”

Su Xi Rong detail, 75, (b. 1933).

Jo Farrell

Zhao Hua Hong portrait, 84, (1926–2013).

Jo Farrell

Farrell will give a talk about her work at the Asia House in London on June 15.