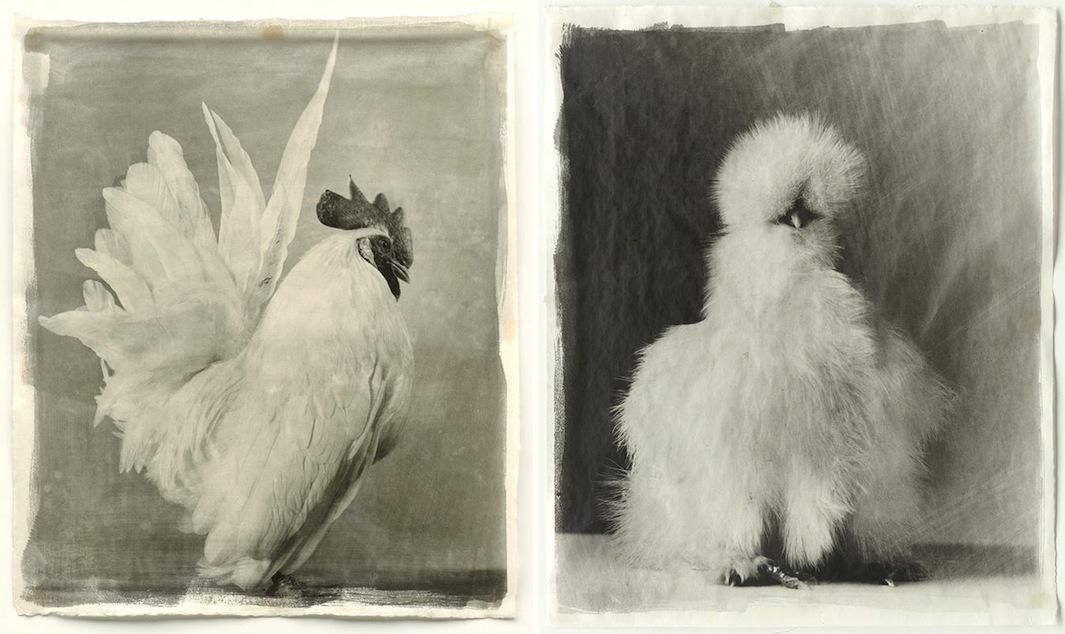

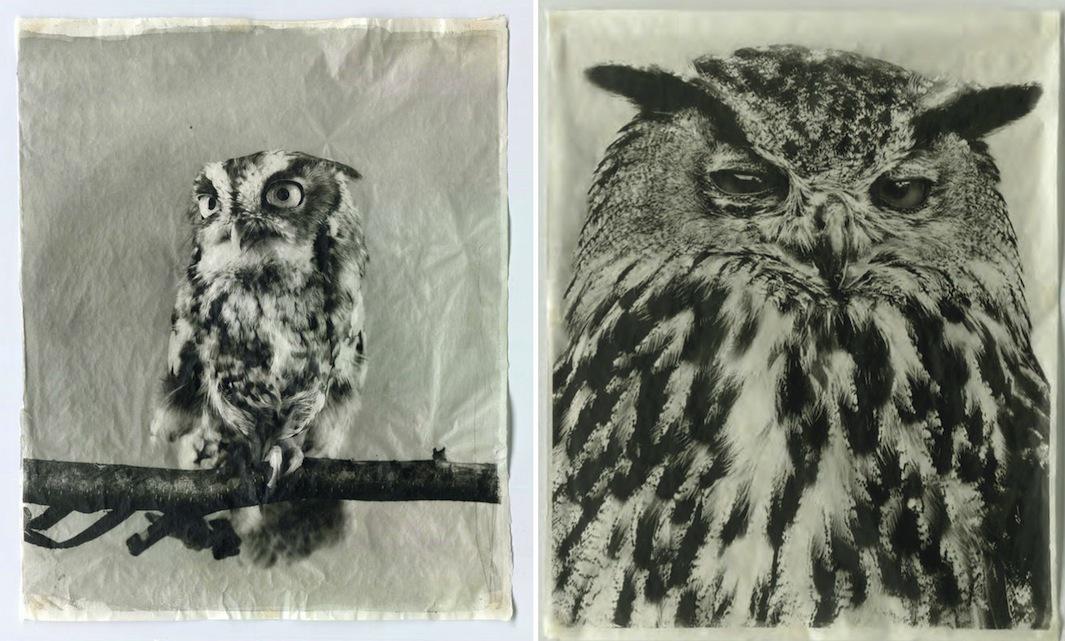

For much of her decades-long photography career, Jean Pagliuso has focused her lens on models, actors, and other glamorous personalities, working for publications like Mademoiselle and collaborating with major film studios. In the past 10 years, she’s widened her interests outside the strictly mammalian to include chickens, owls, and raptors. Her photographs of the winged creatures are on display in the exhibition “Poultry and Raptor Suites” at New York’s Mary Ryan Gallery until May 9.

Pagliuso’s newfound interests emerged after her father died. He raised show chickens, and, to honor him, Pagliuso decided to photograph one, the same way she’d photographed one of the roses her mother grew after she died. All of her father’s birds, however, had been given away by the time she got the idea, so she reached out to an animal talent agency and requested some birds.

“They were nothing like my dad’s,” she said. “I said, ‘Where are the feathered feet?’ They said, ‘They probably lost them in transit.’ I said, ‘No, I want better chickens.’ Still I photographed them. Even those very ordinary looking chickens, I was like, ‘Wow, these are beautiful.’ ”

Jean Pagliuso

Jean Pagliuso

Pagliuso has stuck with the project over the years because of the sentimental connection she draws between the birds and her late father, and also by her own aesthetic interest. The handlers bring the birds directly to her Chelsea studio—they cackle as they’re transported down the hall, drawing the attention of neighbors—and Pagliuso photographs them with her Hasselblad camera in front of a cement wall. She prints the images on Thai Mulberry paper in her darkroom, a labor-intensive, days-long process that gives them the look of graphite drawings.

“I don’t see it as any different at all from photographing people. It’s exactly the same to me. I look for the same things. I look for form and the way the frame is filled,” she said.

Pagliuso says the chickens are usually quite well-behaved and cooperative during their portrait sessions. Playing music, particularly Australian didgeridoo, in the studio tends to soothe them, and Pagliuso said she’s figured out how to establish a special rapport with the animals. “I know this sounds crazy, but I can actually talk to the chickens. I can get them to calm down and look where I want them to look. I have a total affinity for them,” she said.

Jean Pagliuso

A few years ago, Pagliuso expanded her project to include owls and other raptors. Unlike the chickens, she doesn’t have any particular attachment to the birds, and thinks of them more as “beautiful oddities” than totems of her father. Still, she said, the birds are “extremely haunting,” and interesting in their own way. One of her favorites has been the northern white-faced owl, or “Transformer Owl,” which can completely alter its appearance when faced with threats in nature.

“He can make himself about two inches thick. He saw a plane coming up the Hudson River while I was photographing him, and he did the whole transformer thing. We were on the floor it was so hysterical,” Pagliuso said.

Hirmer Publishers will release a book of Pagliuso’s chicken photographs this summer in the book, Poultry Suite.

Jean Pagliuso