Richard Ross has been photographing the juvenile justice system for nearly a decade and has visited youth detention centers in more than 30 states. The system, Ross says, can get kids out of immediate danger, but it doesn’t do enough to help keep them out of trouble in the future or change the conditions that put them there in the first place.

“We say, ‘It’s better than having them on the streets.’ But that doesn’t address the issue of why their neighborhoods aren’t better places to live. Just by the zip codes they’re in. It’s more likely these kids will go to jail than college. The kid hasn’t failed; we’ve failed,” he said.

Part of making reform happen, he knows, is getting people to pay attention to the issue. That’s why, three years ago, he self-published his first book-length exploration of youth in detention, Juvenile in Justice. In February, he published another, Girls in Justice, which collects the photos and testimonies of girls around the country. Girls are the fastest-growing population in the juvenile justice system, accounting for hundreds of thousands of arrests and charges—often for minor offenses, like running away from home or breaking curfew—every year.

As with Juvenile in Justice, he hopes this project will raise questions about why kids end up in detention centers, and what can be done to ensure they have a better shot at life once they leave.

Richard Ross

Richard Ross

When Ross visits girls at detention centers, he first knocks on the doors of their cells and asks them for permission to enter. If he’s granted it, he takes off his shoes, sits on the floor, and talks with them for about an hour. Often, he said, the conversation turns emotional, as the girls recount childhood abuse and neglect, often followed by stories of homelessness, drugs, or prostitution. He hears a lot of the same kinds of personal histories over and over again, and often meets girls who’ve been in and out of the system several times.

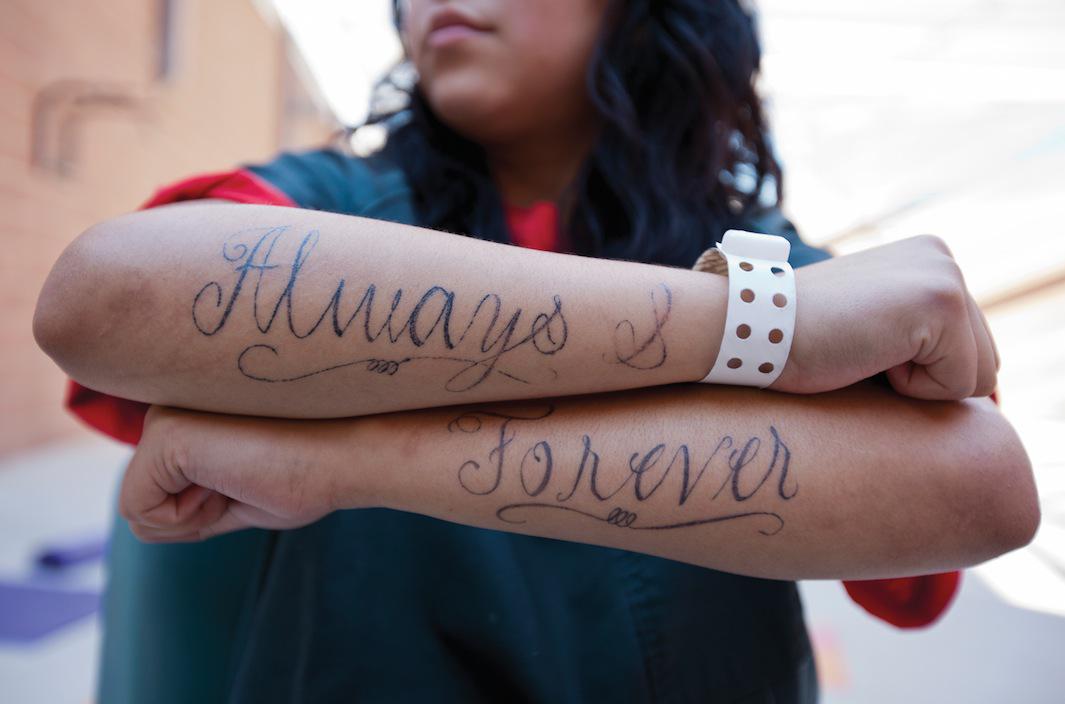

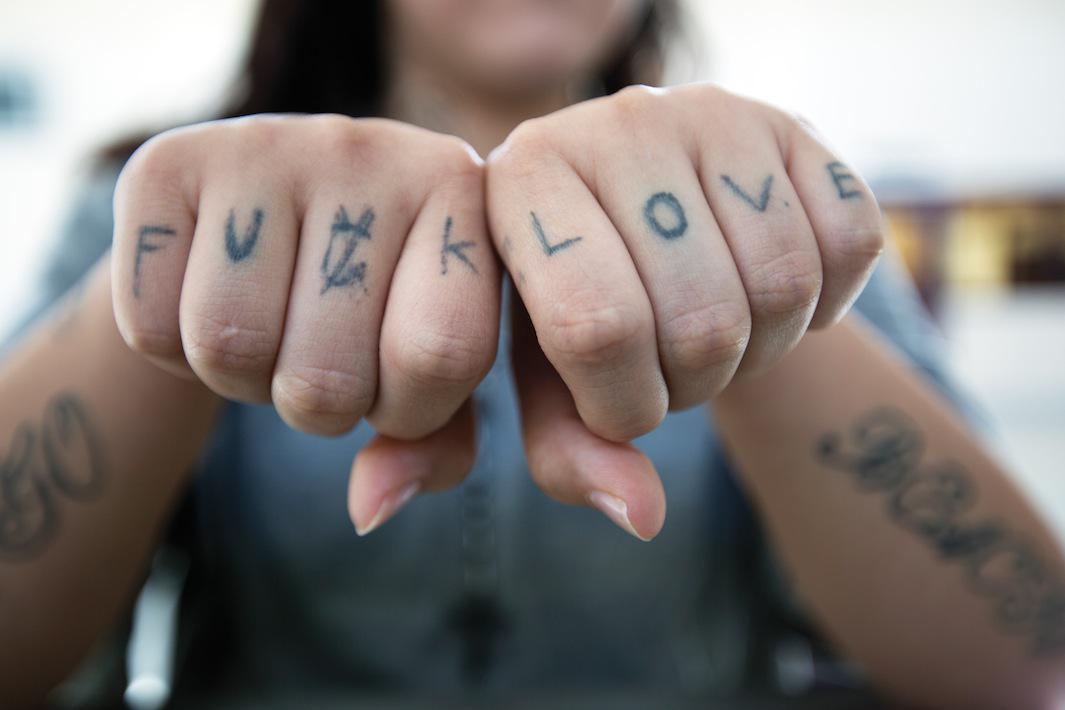

In his photos, Ross either blurs out the faces of his subjects or frames them so that they’re obscured. He does it, he said, because he doesn’t want them to be followed throughout their lives by evidence of their time in detention. But it also serves an artistic purpose—one that he hopes will impact viewers of his work.

“If you see a face, you can say, ‘Well, I’m glad that’s not my kid,’ ” he said. “But if the face is obscured, it could stand in for anybody’s kid.”

Richard Ross

Richard Ross

Richard Ross

While Ross wants readers to understand the direness of the situation in juvenile justice, he doesn’t want them to lose hope in his subjects. He believes that with the right care and allocation of funds these girls can “not just survive but thrive.” He also wants readers to know they have power to help bring about change in the system.

“The first step is to think about it. The next part is to think that you’re not impotent to change the system, and to make demands on people that administer taxes and funds. Ask about the treatment of these kids and ask why it’s that way.”

You can follow Ross’ work on Facebook and Twitter, and on the Juveniles in Justice website.

Correction, April 27, 2015: A photo caption in this post originally mispelled the city of Asheville, North Carolina.

Richard Ross

Richard Ross

Richard Ross