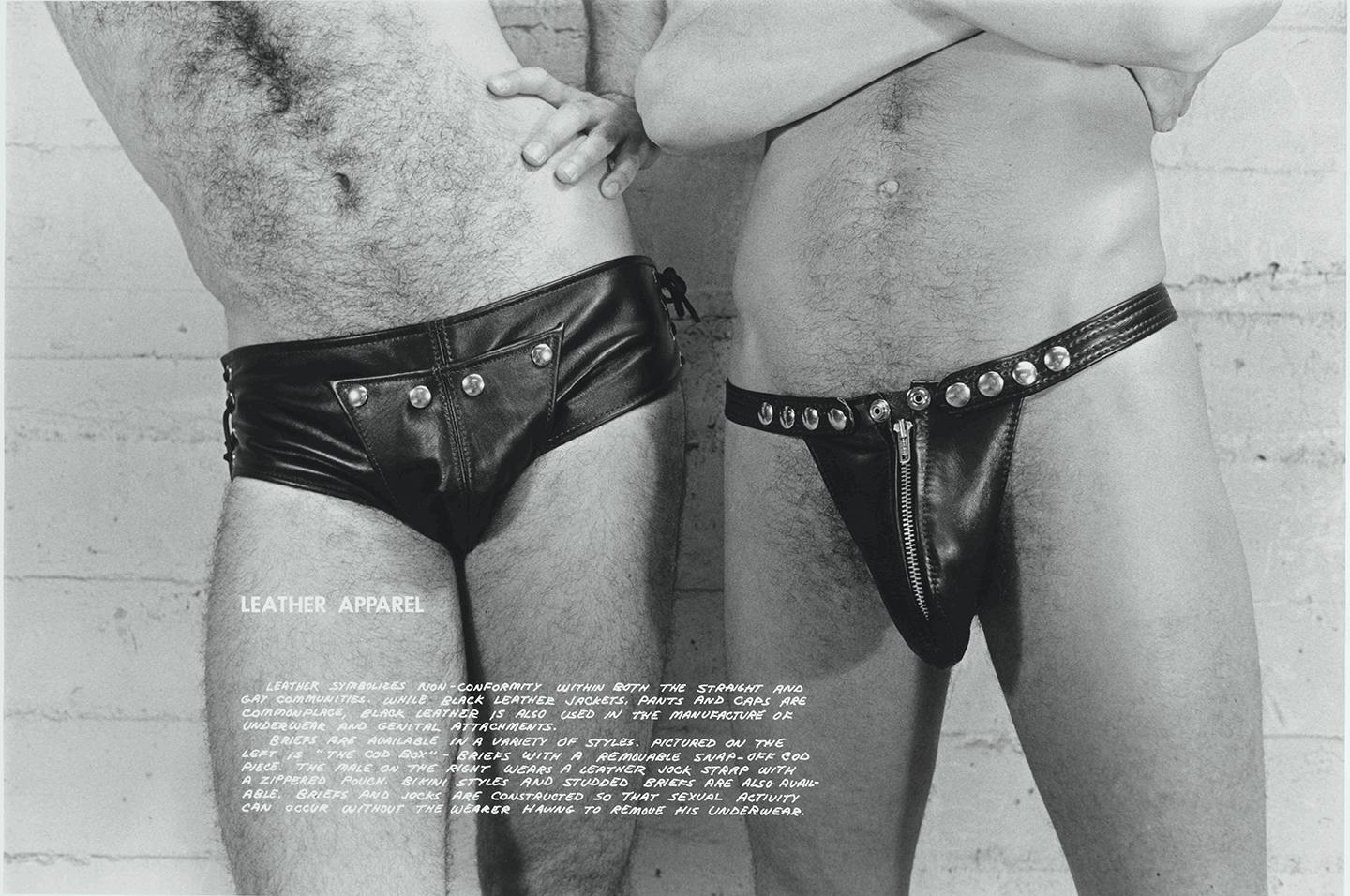

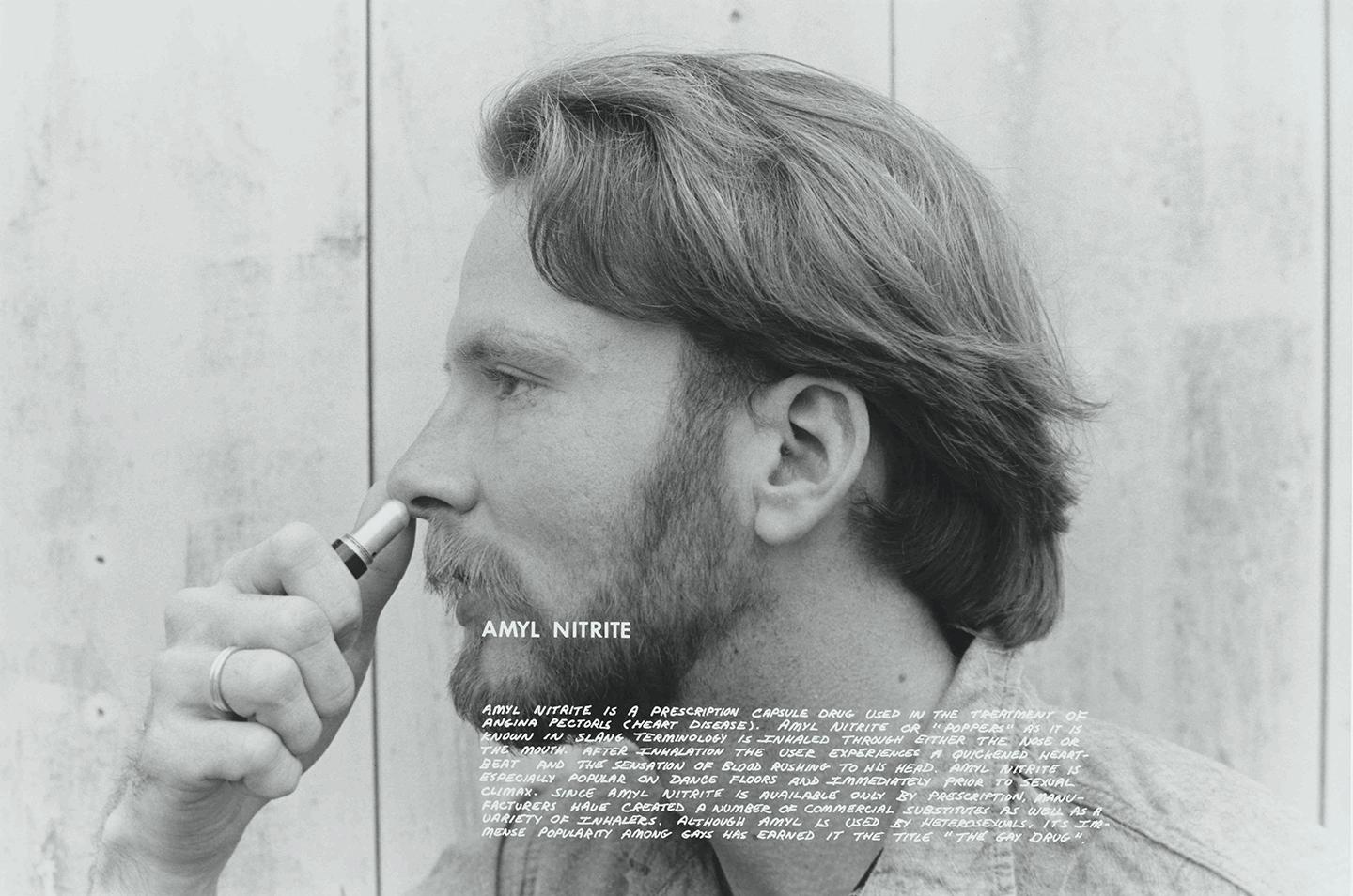

Hal Fischer’s 1977 book, Gay Semiotics, is a tongue-in-cheek look at gay life in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood. If the same type of work were attempted today, say in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen or Chicago’s Boystown or even in the Castro, the work wouldn’t walk the same fine line of artistic expression and anthropology. That’s because Fischer was uncovering a way of life that wasn’t celebrated outside of the gay world.

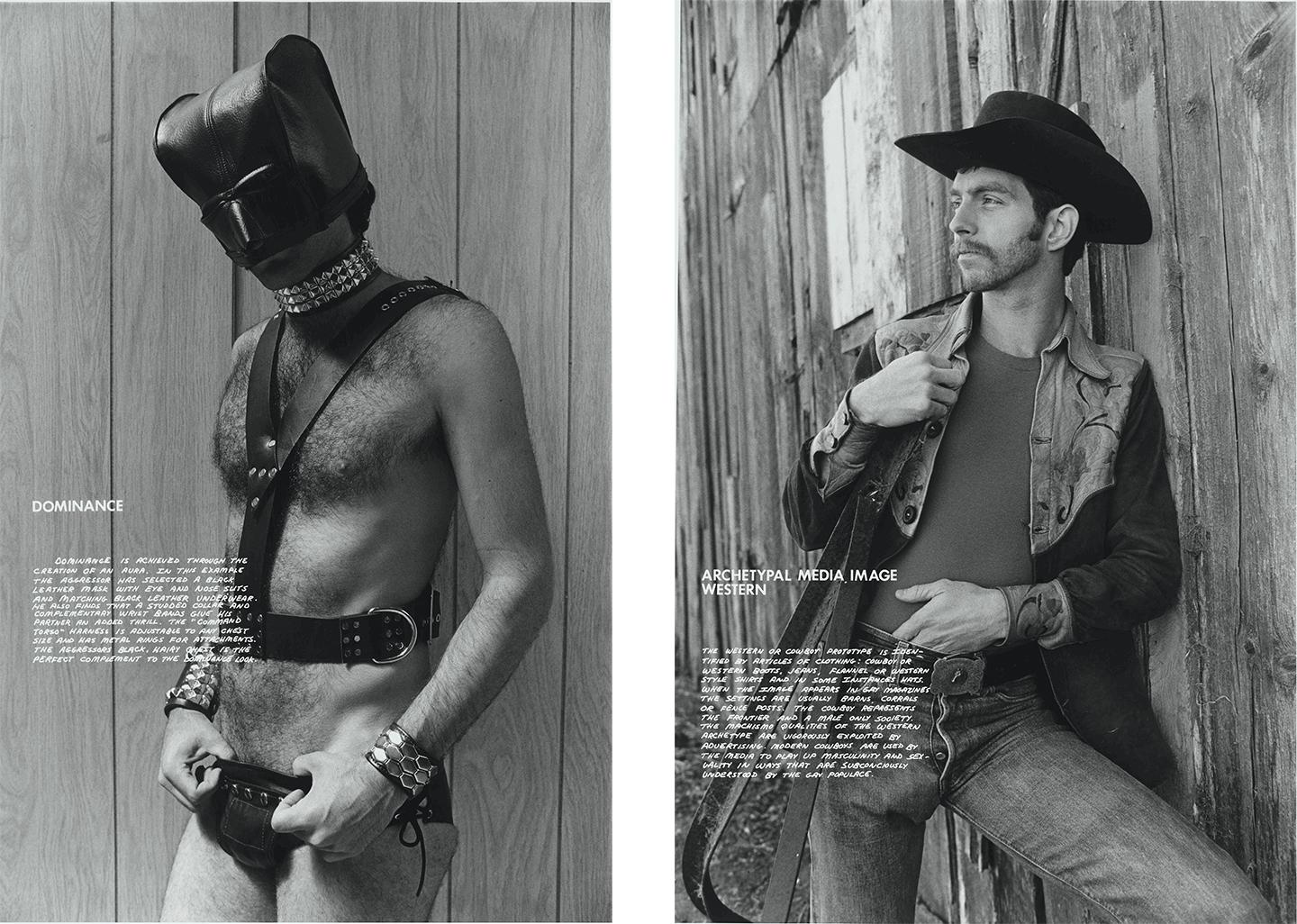

“I was exposing something and I was celebrating it by using text and a certain way of photographing in a very deliberately artificial way to disarm it, to not make it threating,” Fischer said. “This isn’t Mapplethorpe doing S&M work, this is a 180-degree opposite.”

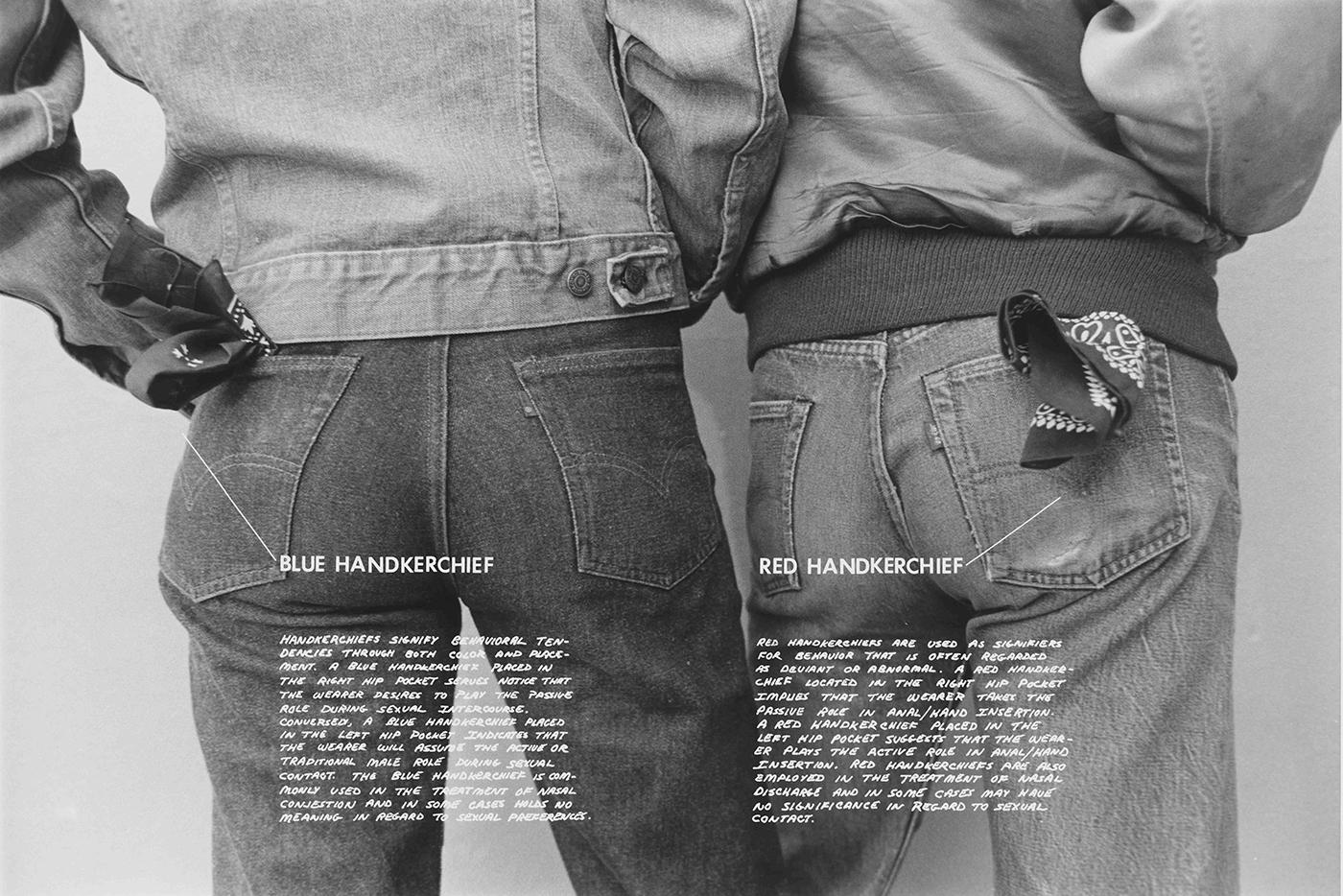

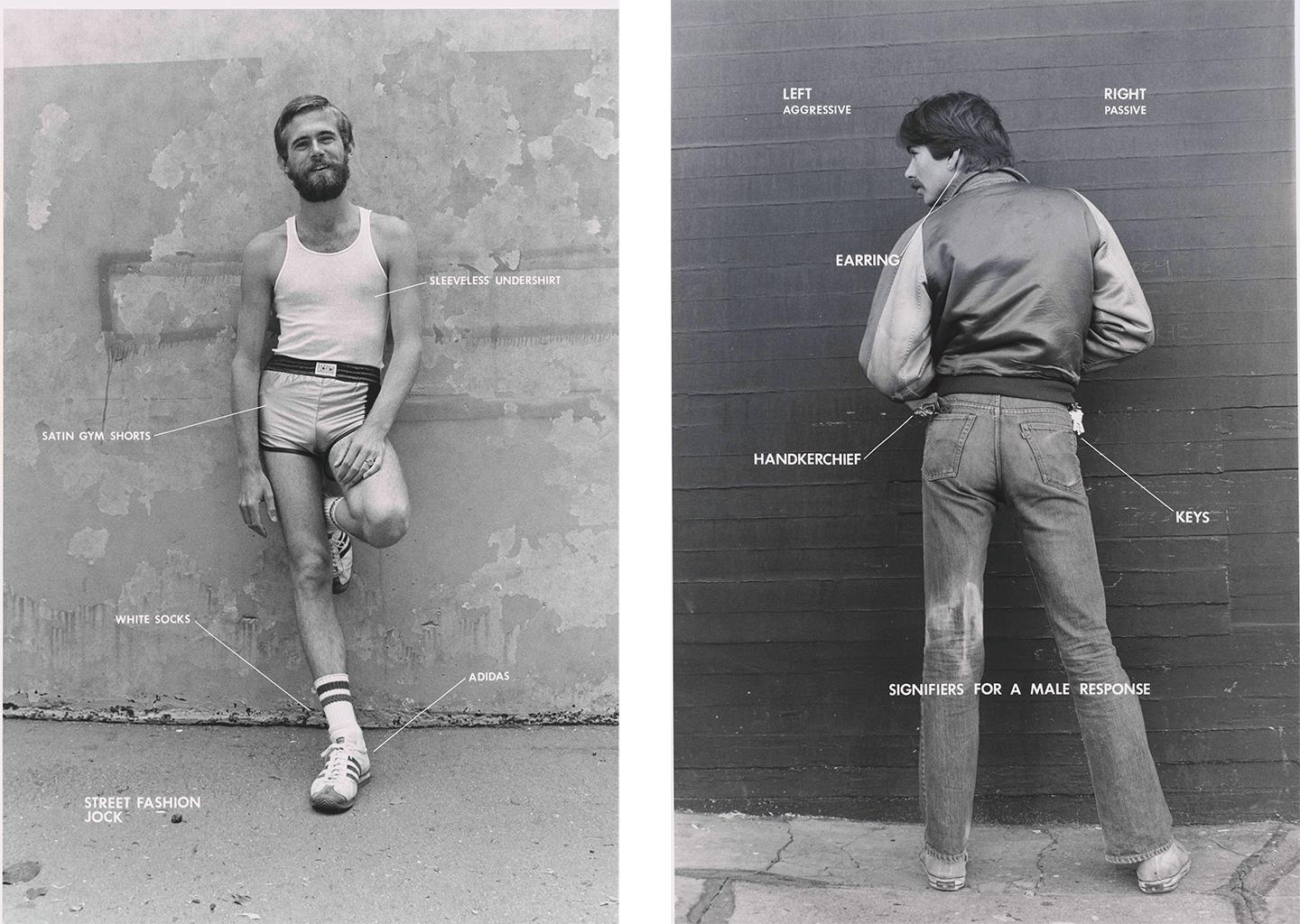

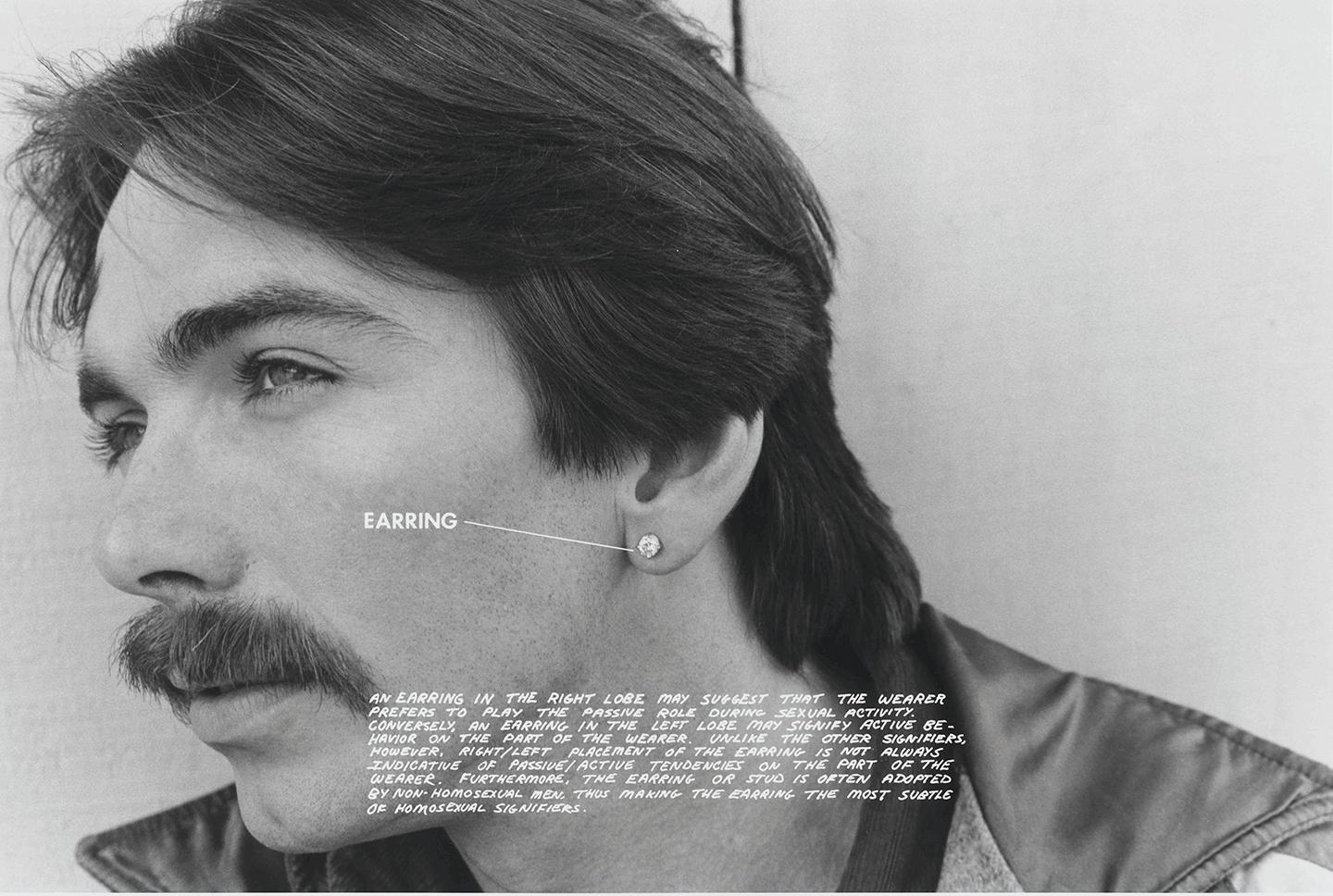

The work feels like a precursor to some modern-day blogs that combine street photography and portraiture—like The Sartorialist or Advanced Style—but with a focus on the various subcultures within the gay community. In the work, Fischer provided a humorous take on the various subtle methods of communication and identification gay men partook in during that time: donning handkerchiefs to identify sexual preferences or how to properly wear cowboy attire to fit into the archetypal Western prototype.

“At that point in time, any kind of gay presence that went public was celebrated because it was out there in a way that things had been closed off, you didn’t have gay characters on television,” he said. “I think there was a real sense that anybody that was doing work that was gay and got out there and became more mainstream and ended up in publications or in a museum was a good thing.”

Fischer’s previous work combined photography with drawing or painting, but for Gay Semiotics he decided to add text onto the images instead. It turned out to be a laborious process, one that he describes as a “low tech” way of doing things; it certainly wasn’t as simple as opening Photoshop and adding words. The text was printed onto acetate and the negative was then exposed through the acetate, which is why the lettering is white.

“It was really about an approach to photography that was informed by structuralism and French philosophy and really one that was anti-metaphor,” Fischer said. “I was using the size of the text against the image so to read it from a distance would seem like an advertisement and then when you got closer you might think, What’s he talking about?, but then I would disarm that by using humor.”

Hal Fischer, courtesy Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles

Hal Fischer, courtesy Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles

Hal Fischer, courtesy Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles

“This was in the Castro, which was very white male, but it represented a certain milieu that existed here,” he said. “There’s so much of the personal in this work, it’s my milieu, particularly the humor I used in it. I couldn’t have gone out to anyone else’s culture and used that humor—I could have done Jews—but that pretty much ends it!”

Almost 40 years after its initial viewing, the work was shown at Cherry and Martin in Los Angeles through the end of February. For Fischer, it provided what he calls an extra 15 minutes of fame (“or 7½ twice”).

Hal Fischer, courtesy Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles

“What I’ve noticed from young gays is a real interest and passion for reclaiming history so the response I’ve gotten has been really great,” he said. “To see people enjoying the work is really fun and gratifying.”

Hal Fischer, courtesy Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles