After completing an installation of photographs based on Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights, at the University of Virginia in 2013, Elisabeth Hogeman flew to Giverny, France, to spend three months living at an artist residency in Monet’s gardens where she set out to work on a project that would incorporate the relationship between conceptions of Eden and bodily experience.

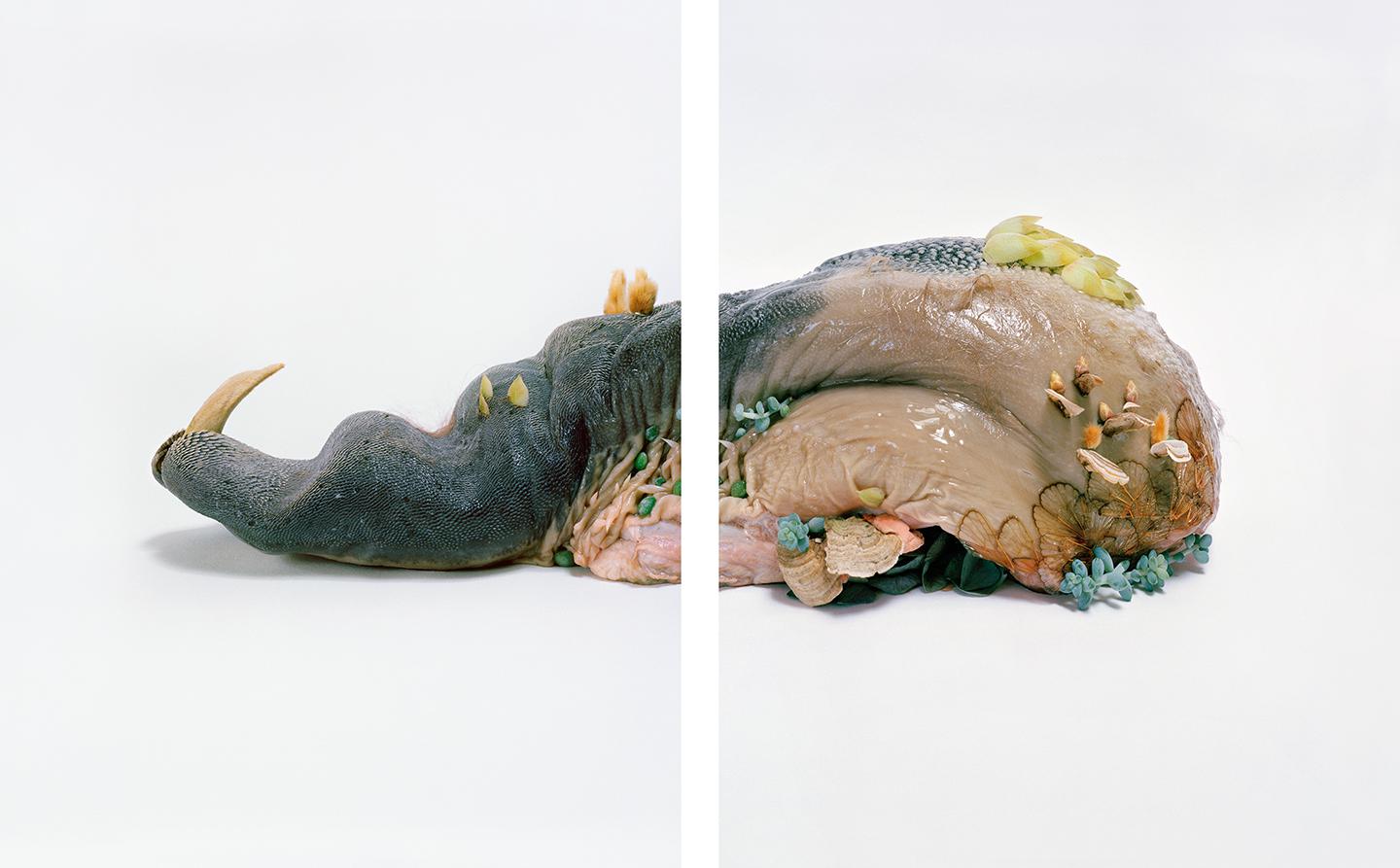

The result was the series “Geographic Tongues,” made up of five diptychs of highly stylized cow tongues. At face value, they are meant as a reinterpretation of the exterior panels of the original altarpiece in Bosch’s work, specifically an image of the world floating in a nondescript space, divided across two panels with an inscription from Psalms, “For he spoke and they were made.”

“I was drawn to the idea of speaking a world into being,” she wrote via email. “And how any visualization of that process would always be a kind of failure or stillborn. I like the idea of language as something to be looked at.”

To create a world of visual language, Hogeman headed to a butcher shop in Vernon where she purchased the tongues that would be her substitute Earth. Though they were unwieldy at first, Hogeman said they were clean and without blemishes or discolorations.

Elisabeth Hogeman courtesy of the artist and funded by the Versailles Foundation, New York

Elisabeth Hogeman courtesy of the artist and funded by the Versailles Foundation, New York

“I became increasingly violent toward them,” she wrote. “In one instance I partially cooked the tongue at too high of a temperature, which caused the meat to seize up, so I bound it into shape by taping it to a plate and froze the tongue.” It turned out to be a happy accident, as the hardened tongue made it easier for her to form nooks for vegetation to grow out of, a nod to the idea of the world emerging from language. She sourced all of the material found both in and around the tongues from Monet’s gardens, apart from the fifth one that she created in Charlottesville. While nothing was intentionally grown in the tongues, some mushrooms did appear. The cold tongue also provided an unexpected aesthetic bonus.

“When the tongue began to defrost, it formed a thick blood pool. I liked the idea of a bleeding landform.”

Since she began showing the work, Hogeman said that people are often confused when trying to figure out exactly what they are looking at.

“To some they appear to be objects that have been decorated rather than singular organisms. Even though I think of decoration as a kind of dirty word, it could generate a productive interpretation, perhaps thinking about death and adornment, like flowers placed on and around a headstone. I think there are multiple readings available to the viewer.”

Elisabeth Hogeman courtesy of the artist andfunded by the Versailles Foundation, New York

Elisabeth Hogeman courtesy of the artist andfunded by the Versailles Foundation, New York