During previous editorial assignments at the University of Texas, Adam Voorhes had come across everything from a set of antique vacuum tubes to a collection of wood letterpress type to a bunch of robots. But no one had thought to show him the storage closet full of brains in the Animal Resources Center until 2011.

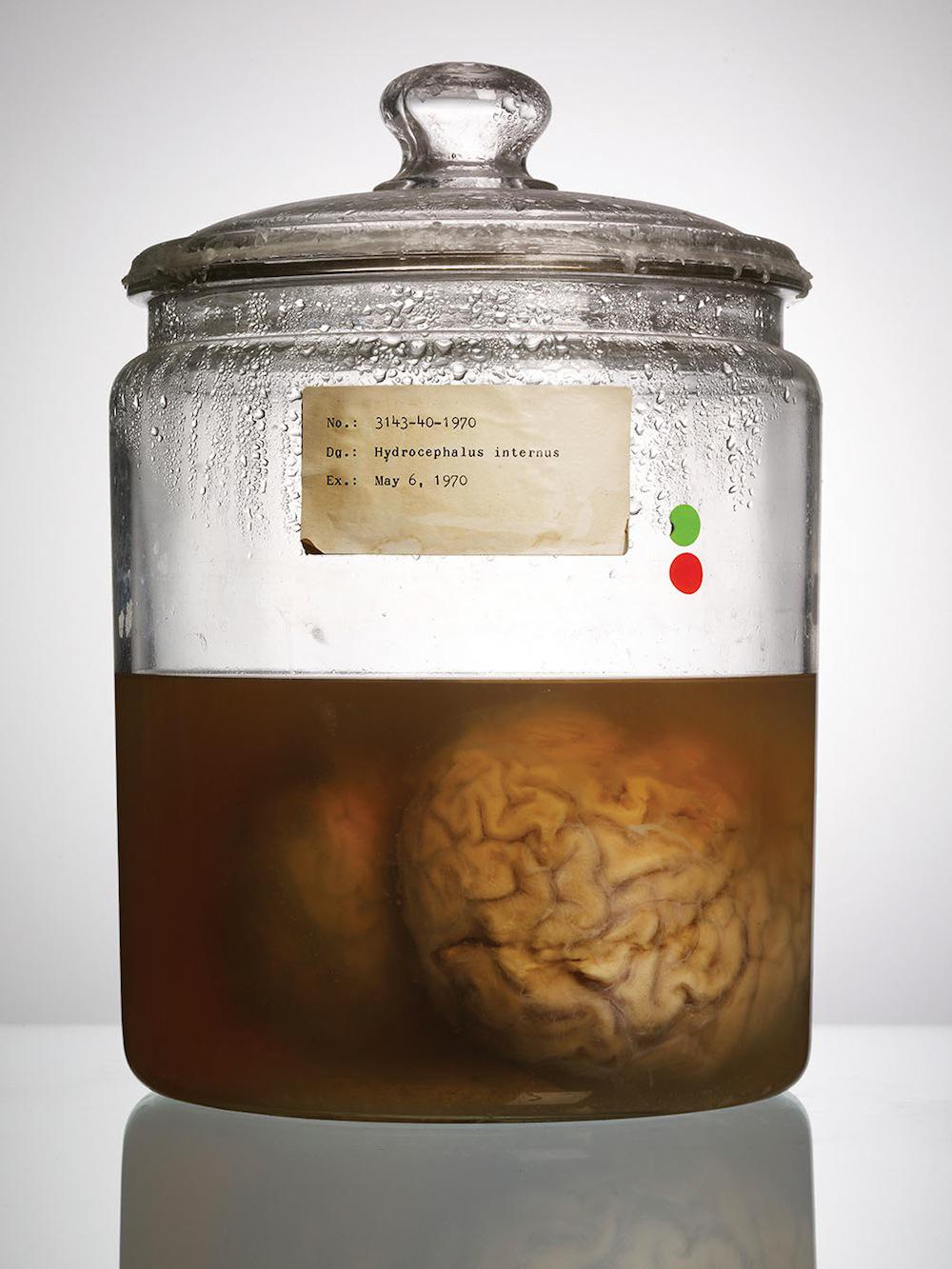

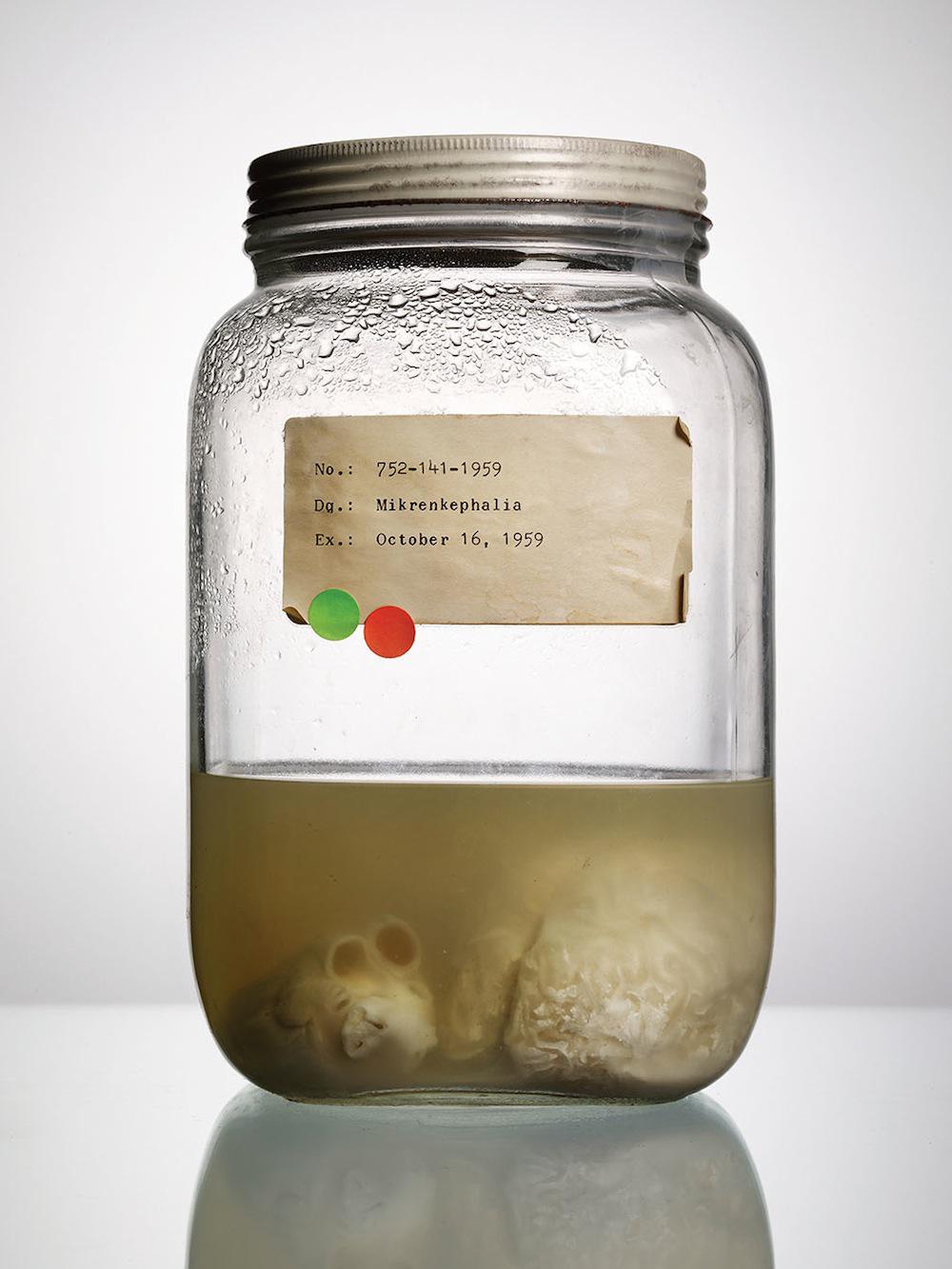

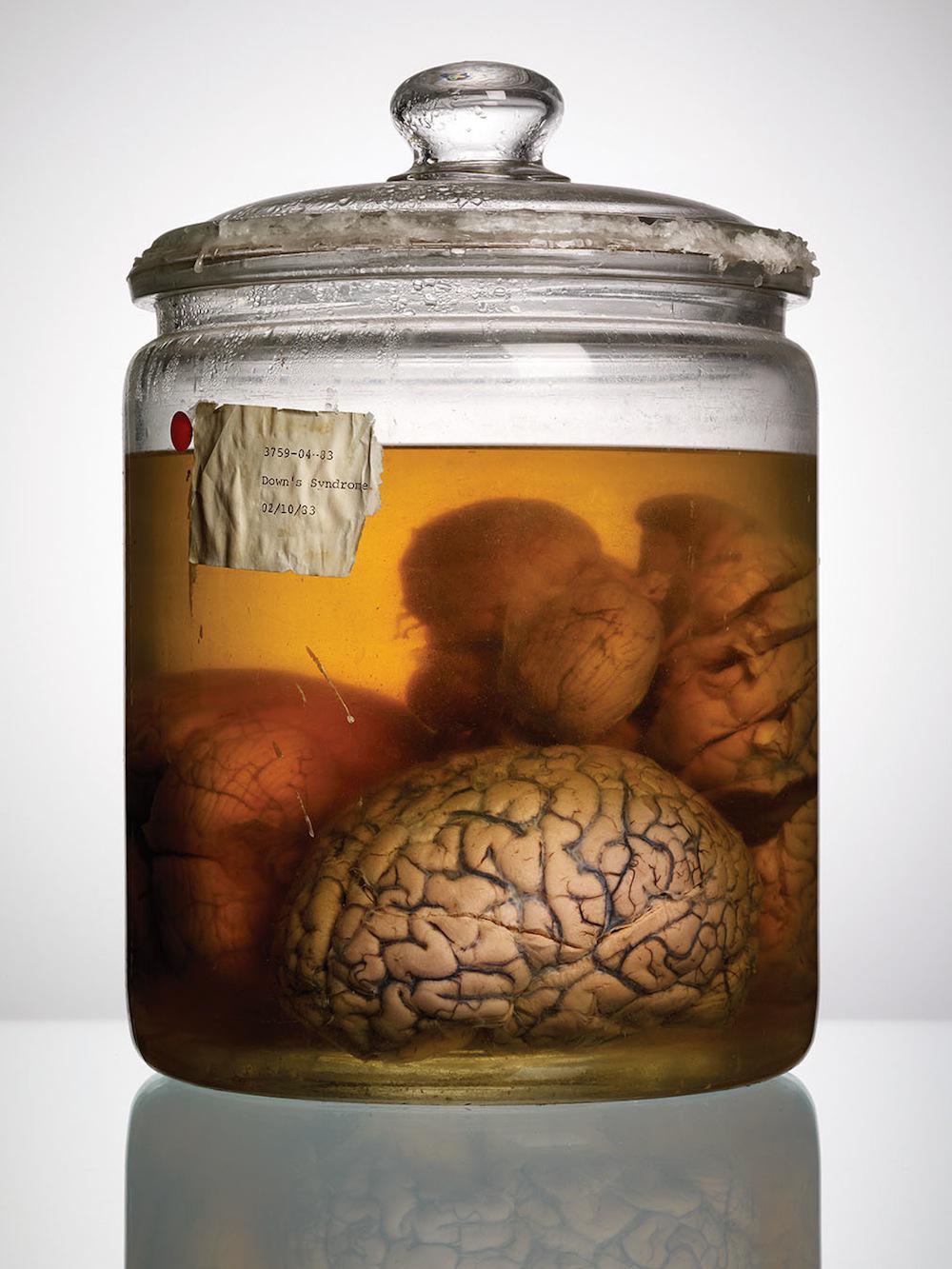

He was at the university to take a photo of a brain—“just a regular brain,” nothing special—for Scientific American. But the 100 brains he found in the closet, which were stacked two jars deep on 10-foot-wide floor-to-ceiling shelves, were far from ordinary. All, in fact, were malformed or somehow abnormal. He decided to investigate.

Adam Voorhes

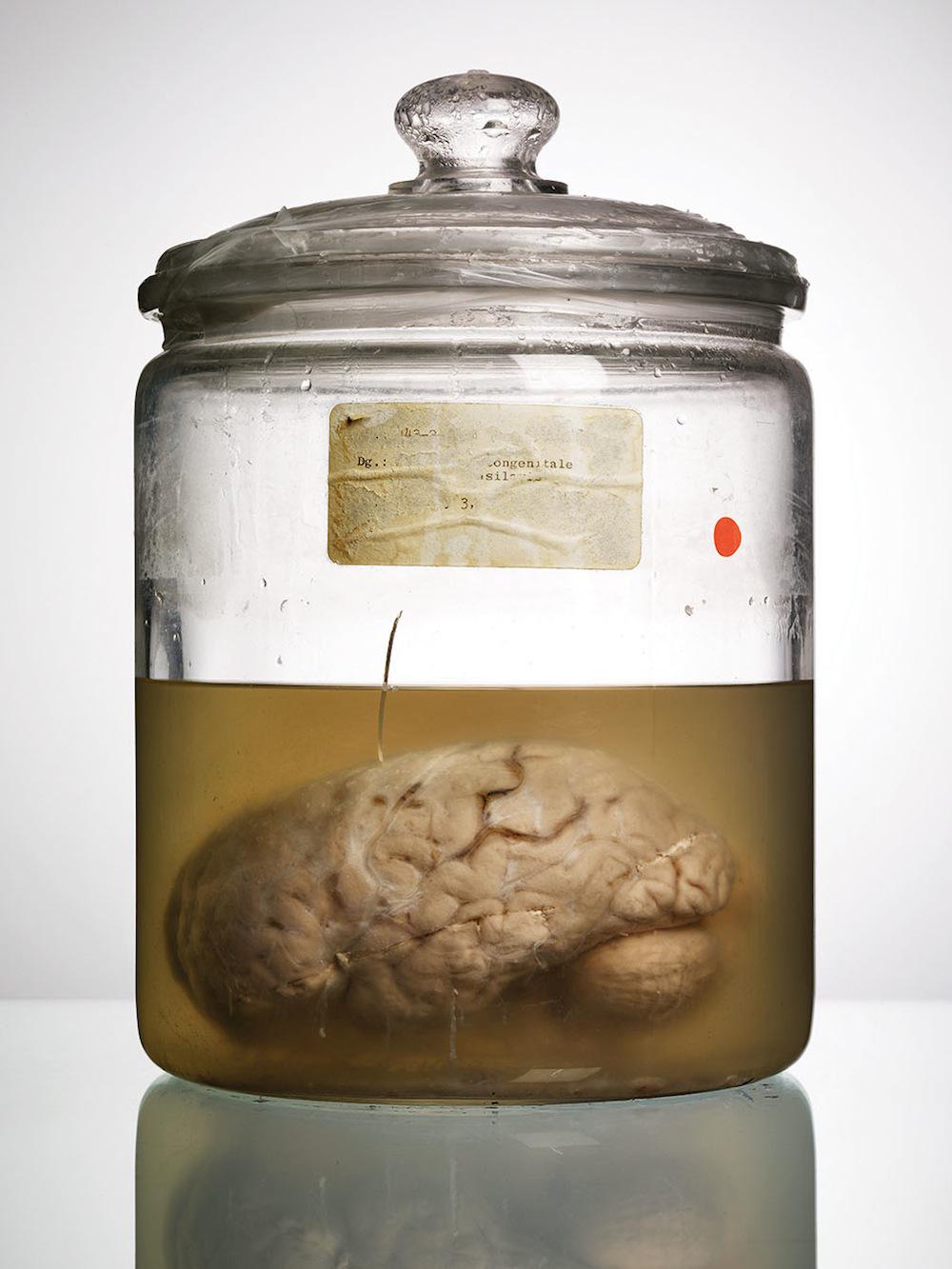

Along with journalist Alex Hannaford, Voorhes traced the history of the brains. Dating back to the 1950s, they belonged to patients from Austin State Hospital (once the Texas State Lunatic Asylum). The collection—rare for its size, age, and diversity—came to the University of Texas as a gift in 1986 (other universities, including Harvard, had tried, and failed, to secure the collection) after the hospital ran out of space to store it. It is currently being used as a teaching tool by the psychology department.

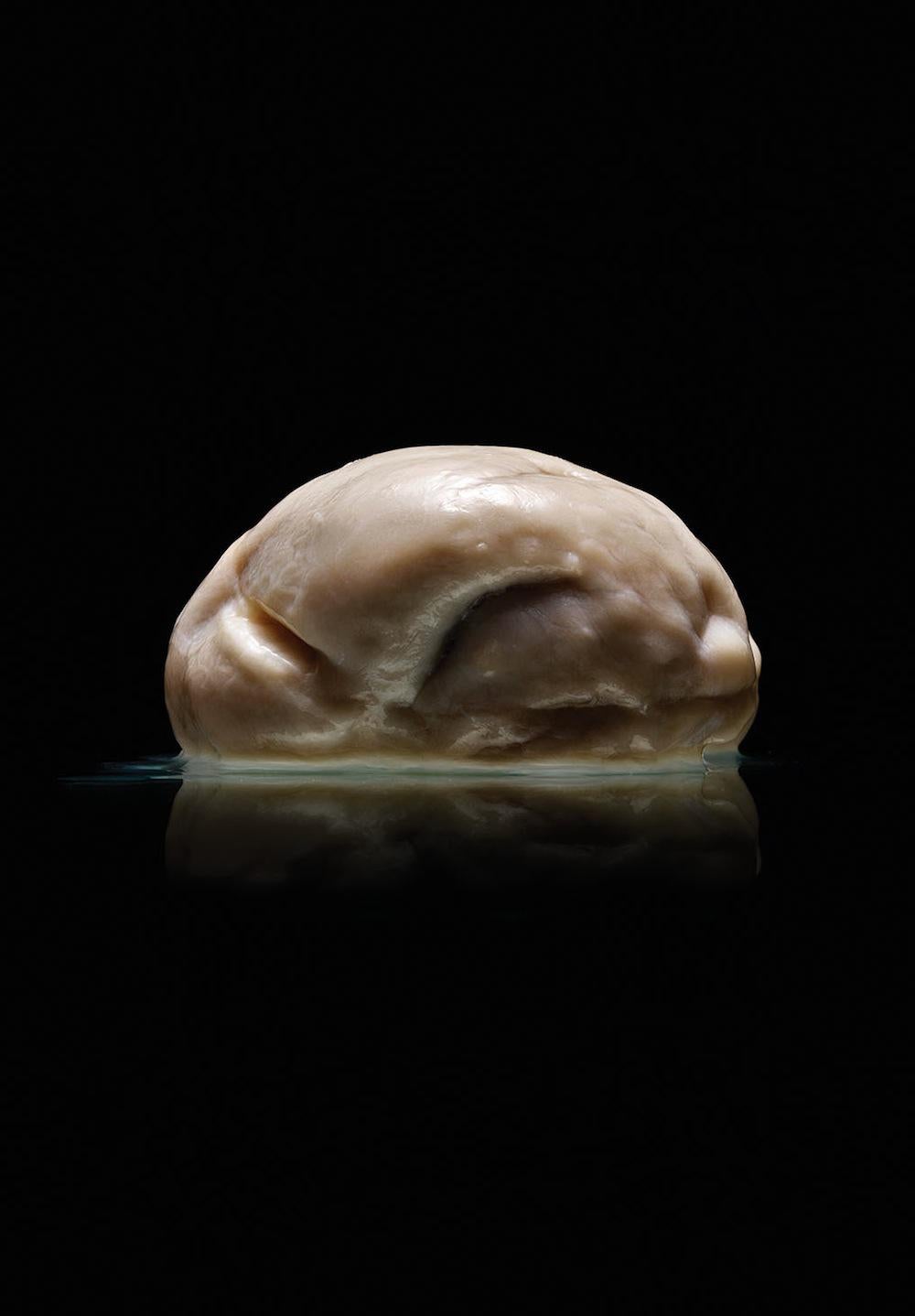

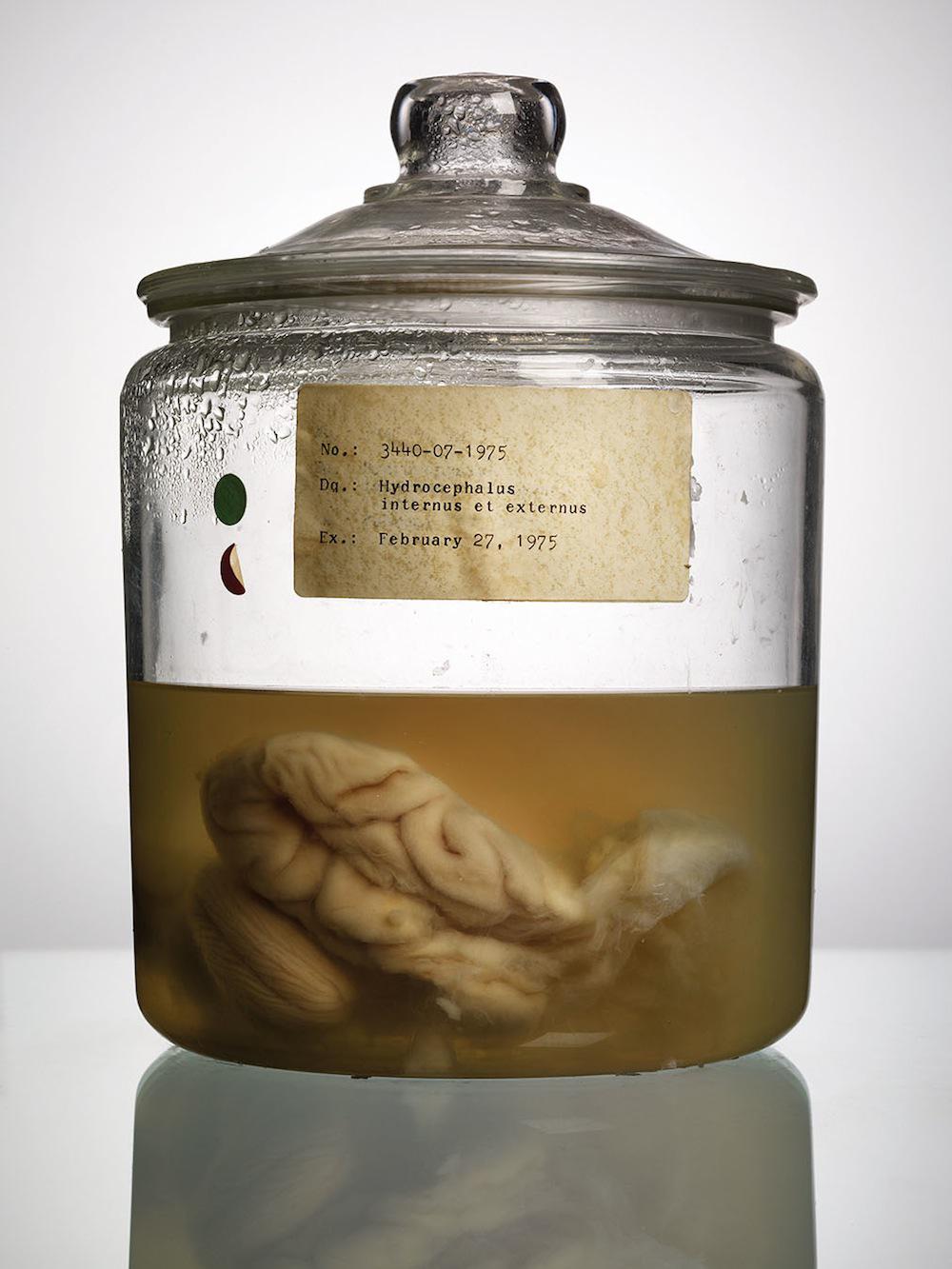

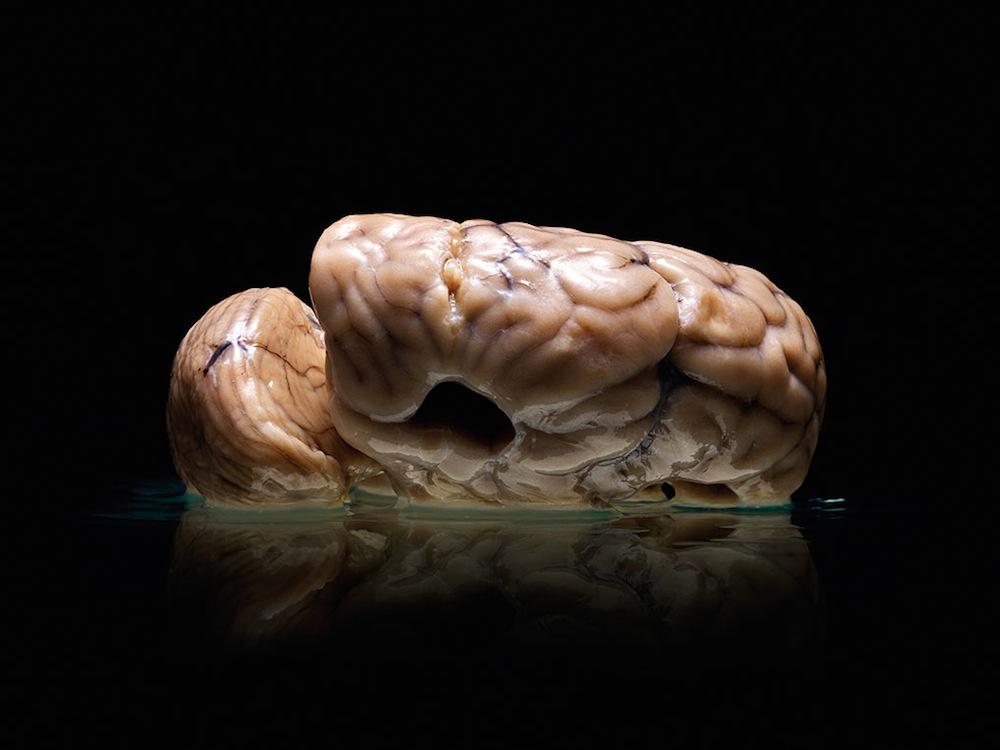

As Voorhes began photographing the collection, he strove for a “clean, graphic, slightly sterile” look, which he achieved through high-resolution, large format images. Donning respirators and heavy rubber gloves, he joined Dr. Neal Rutledge, an Austin-based neurointerventional surgeon, and Tim Schallert, a University of Texas professor, in a makeshift studio in the lab adjacent to the storage closet. For two days, they worked with the brains and Voorhes captured more than 200 images in total, many of which will be published in an upcoming book, Malformed: Forgotten Brains of the Texas State Mental Hospital, out from PowerHouse Books last month.

“I wanted to study the collection with light, try to make it as beautiful as possible, but not manipulate or misrepresent anything. I wanted to study the texture of the brains, the labels, the wax dripping down the glass, cracks and chips in the jars,” Voorhes said via email.

Adam Voorhes

Adam Voorhes

Some of the brains were firm and easy to handle. Others, however, were heavily damaged by cysts, Alzheimer’s, or meningitis and therefore too delicate to remove from their jars. Among the brains were rare specimens including a “smooth brain” belonging to a patient who suffered from Lissencephaly. “Many of the patients suffered from disorders that could be managed today. … I’m surprised they passed away in a mental hospital rather than an emergency room,” he said.

Even as science journals have published new research about the brains, and the University of Texas has begun creating MRI scans of the specimens, the collection is still surrounded by mystery. According to Hannaford’s research, the collection was originally twice its current size—but nobody knows how 100 human brains disappeared from the university in the past 30 years. One of those brains belonged to Charles Whitman, who, in 1966, killed 16 people and wounded 32 others at the University of Texas at Austin.

For a while, Hannaford and Voorhes searched for microfilm containing patient records, but the effort lead to a dead end. Still, Voorhes hopes his project will inspire more investigation and secure the collection’s continued maintenance.

“I wanted to preserve the collection, if only visually,” Voorhes said. “It spurred so many questions that kept floating around in my head, most of them are still unanswered.”

Adam Voorhes

Also in Slate: “Human Brains in Jars at Yale’s Medical Library”