Bradley L. Garrett, who has a background in archaeology, knew almost nothing about London when he moved there in 2008 to pursue a Ph.D. Now, he’s created the most comprehensive photographic account of subterranean London ever produced: Subterranean London: Cracking the Capital, recently published by Prestel. “It just goes to show how much things can change when you devote yourself to learning a place from the inside out,” he said.

For the last six years, exploring (or writing or talking about it) has “dominated almost every waking hour” of Garrett’s life. He’s also explored in Paris, Chicago, and Las Vegas, experiences which are documented in his first book, Explore Everything: Place-Hacking the City. But when he first started, he was just struggling to get a toehold in London’s exploring community.

Bradley L. Garrett

Bradley L. Garrett

After trying to make connections on message boards for six months, an explorer who goes by Midnight Runner finally agreed to show him around. They went to a derelict mental asylum called West Park where Garrett met Winch, a core member of the London Consolidation Crew, a collection of the city’s best explorers who went out night after night on “an endless rampage.” Over the next “breathless” few years, Garrett uncovered dozens of locations with the LCC.

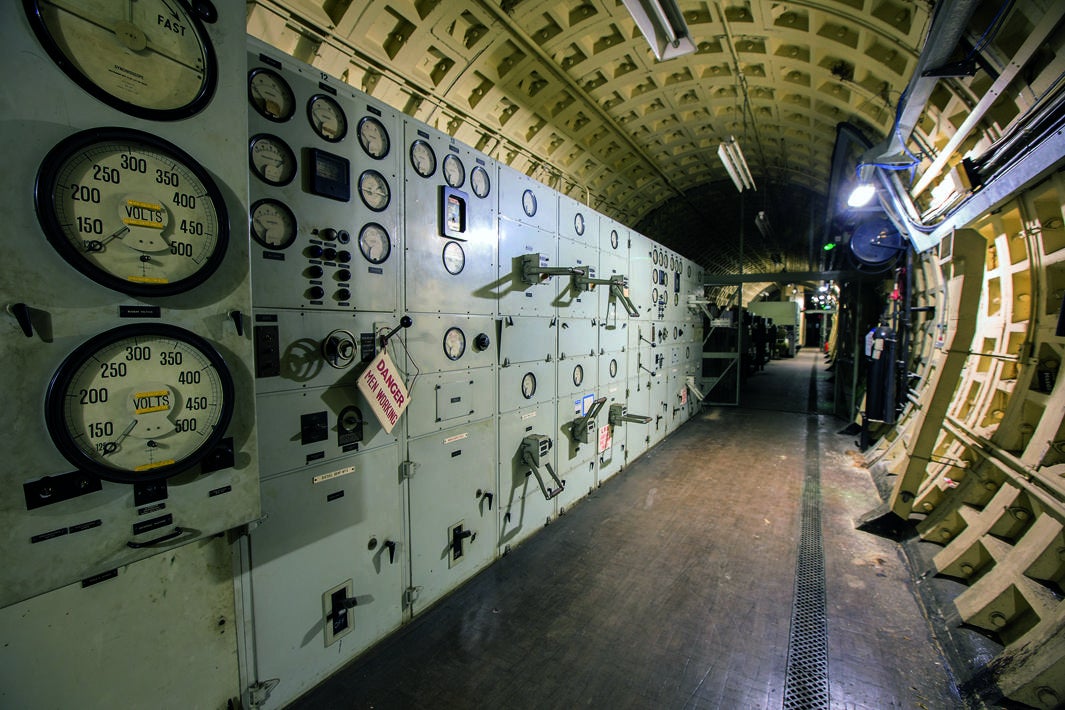

Every city has its own unique underground, but the spaces under London, Garrett said, are particularly expansive and diverse. Among the sights to be seen are hundreds of miles of sewer systems, electricity and telecommunications tunnels, more than a dozen abandoned metro stations, and Cold War bunkers. All of the places in Garrett’s book were accessed and photographed (often using a handful of tripods and LED lights) without permission.

“We all know though that if we had asked for permission, we would not have been given it, at least not without paying hundreds of thousands of pounds,” he said. “I don’t think we should be obliged to ask for permission or pay anyone to photograph public infrastructure—it’s our city.”

Bradley L. Garrett

Bradley L. Garrett

Bradley L. Garrett

Exploring the underground is dangerous business, and Garrett and his friends risked death and arrest “almost every night” to do it. By way of example, Garrett recalls a time when four of his friends were in a sewer when an unexpected downpour started. By the time the four made it back to the manhole, the water in the sewer had risen up to their chests and bags and cameras had long been swept away.

“If you’re going to go exploring, you need to know what you’re getting into and you need a torch that won’t die on you and another as a backup. Checking batteries can be the thing that saves your life if you get stuck somewhere. But that’s an adventure too. If we knew what was going happen, it wouldn’t be exploration.”

Garrett doesn’t necessarily expect readers of his book to go wandering in abandoned metro stations, but he does hope his adventures inspire them to “do something subversive” on their own.

“Many times, it is those things which you might not think are a productive use of time that spark the most exciting ideas,” he said. “So I’d say just get out there, don’t take a plan or a map, don’t even have a goal necessarily. Just go and try new things. You don’t need permission for that and you need to stop waiting for it.”

Bradley L. Garrett

Bradley L. Garrett