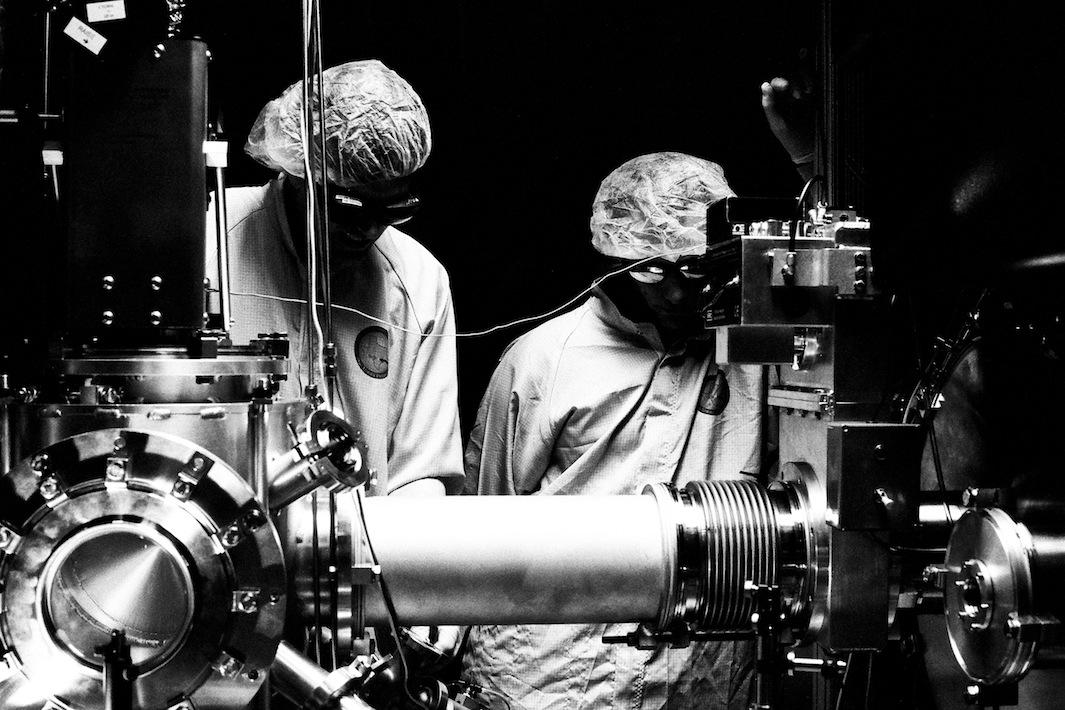

When Robert Shults tells people about the Petawatt Laser, a machine that at one time produced the most powerful laser pulse in the world, the response he hears most often is, “It sounds like something out of science fiction.” In Shults’ new book, The Superlative Light, out this month from Daylight Books, it also looks like science fiction.

And that’s no accident: Shults likes making photos that explore the “intersection of accurate document and open-ended narrative.” After visiting the Texas Petawatt Laser facility in Austin, Texas, in 2009, he was immediately awed: The science conducted there, he said via email, was “indistinguishable from magic.”

Robert Shults

Robert Shults

Robert Shults

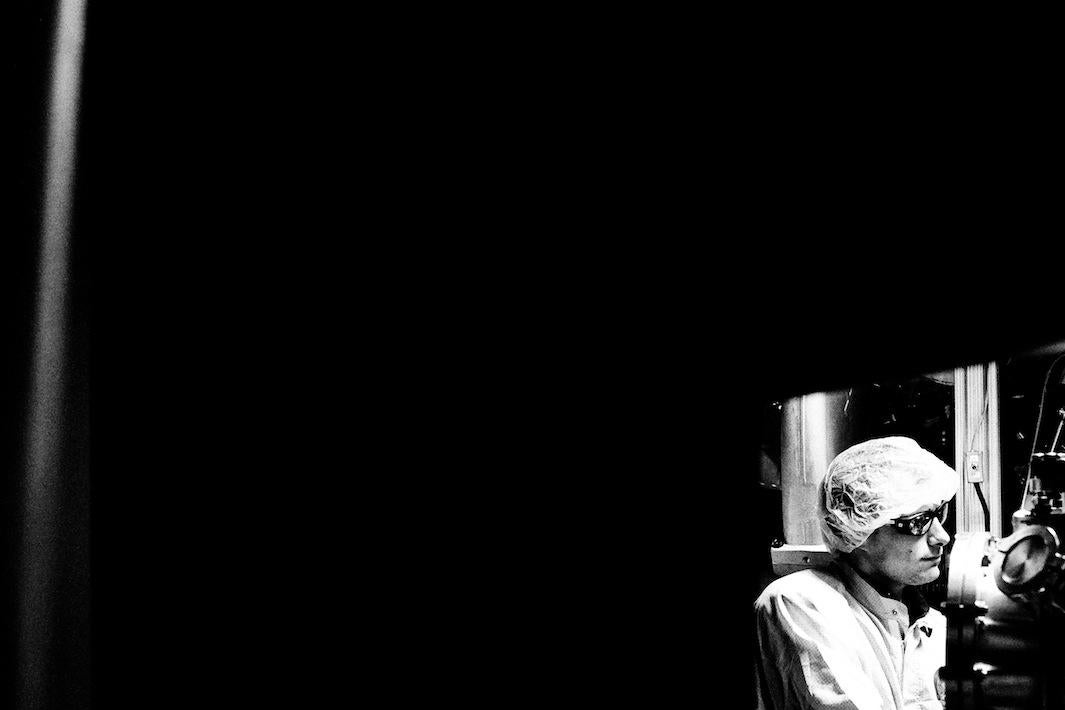

In order to preserve this sense of wonder for himself and his viewers, he said, he decided to “rely on the visual conventions and memories that most of us, as non-experts, utilize to impose meaning on unfamiliar subjects.” The dramatic, black-and-white photos in the book, consequently, take visual cues from a broad cross section of sci-fi movies, including Chris Marker’s La Jetée, Jean-Luc Goddard’s Alphaville, and Joseph Green’s The Brain That Wouldn’t Die. Using Fuji Neopan 1600 film stock allowed him to produce deep blacks with little expository detail and lower “a mysterious, obfuscating shroud of grain over the proceedings.”

Unlike many sci-fi movies, in which scientists are villains “bent on world domination,” Shults was determined to present an alternative narrative. “Something immensely gratifying that I’ve heard from working laboratory scientists who’ve had an opportunity to see this work, is the notion that the photos elevate their often tedious daily tasks to the realm of the epic,” he said. “They don’t generally see such visual depictions of their jobs, but, indeed, they are performing epic endeavors each and every day.”

The Petawatt Laser is, indeed, pretty epic: In a fraction of a second, it can produce more power than the entire U.S. electrical grid.

Robert Shults

Robert Shults

Robert Shults

Most of this, though, can’t be seen. When the laser is shot, the lab is evacuated. And even if people were around while the laser was fired, they wouldn’t see much: Its wavelength lies outside the range of human vision. “I see my job as not merely describing what a thing looks like, but, rather, what it feels like to interact with that thing,” Shults said. “In this way, I was a sort of layperson-by-proxy in this incredibly unique space, charged with communicating the almost metaphysical density of the laser’s capabilities.”

While Shults said the aesthetic of his images is informed by the fact that he is not a physicist, he said the time he spent hanging around the lab served as a crash course in some very advanced science. In fact, he said, “I realized that I was through shooting this body of work when I arrived at the lab one day, glanced at a computer screen displaying a measure of the pulse’s timing accuracy, and thought, ‘Wow, the auto-correlation looks a lot better today.’ In the year or so that I had been observing this device and its operators, some of the mystery had been lifted; I had learned enough to understand it just a bit and I knew it was time to go.”

The Superlative Light will be available Oct. 29.

Robert Shults

Robert Shults

Robert Shults