For more than a century, South Africa has been known for its mineral wealth. Although the country is no longer the leading global exporter of gold, its mineral resources still account for a significant portion of world production and reserves, and the mining industry remains one of the country’s largest industrial sectors.

But mining comes with major social and environmental costs. In 2011, South African Ilan Godfrey returned to his native Johannesburg from London with the goal of capturing “the forgotten communities that the mining industry has left behind.” His book, Legacy of the Mine, reflects two years of work looking at the personal tragedies of those who have suffered while business has thrived. “ ‘The mine,’ irrespective of the particular minerals extracted, is central in understanding societal change across the country and evidently comparable to mining concerns around the world,” Godfrey said via email. “This enabled me to channel my conception of ‘the mine’ into visual representations that gave agency to these communities. The countless stories of personal suffering are brought to the surface.”

Ilan Godfrey

Ilan Godfrey

Ilan Godfrey

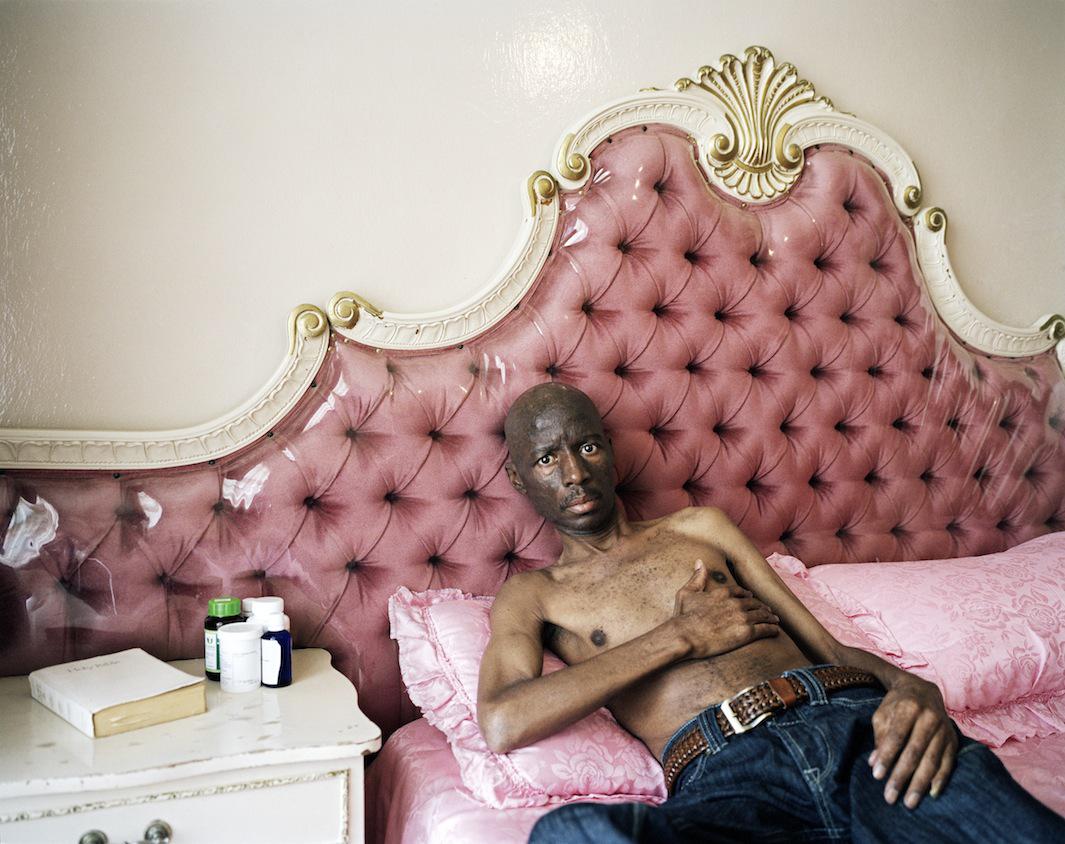

Godfrey’s concern about the health and well-being of miners may be best exemplified by the story of Mahlomola William Melato, a gold miner who, in 2008, was diagnosed with tuberculosis and, in 2010, with silicosis, before losing his job. The mine that employed him provided neither an alternative position nor medical assistance. The government then denied his application for compensation. Last year, Melato died of his illnesses. “Melato’s story is representative of so many men just like him that leave their family and home, traveling long distances to the city in search of work, often finding they have little choice but to join mining operations,” Godfrey said. “Few can afford to return to their community and if they do so many are welcomed back weak and sick.”

While mines do provide jobs in economically marginal areas, Godfrey said, the opportunities are limited. Alcoholism, prostitution, and sexually transmitted diseases are rampant in mining hostels that lie adjacent to mines. Near mine dumps, informal settlements have developed, where communities are at risk of air pollution, fires, water contamination, and other dangerous conditions. Meanwhile, thousands of derelict and abandoned mines are spread across South Africa, where “informal” miners, known as zama-zamas, risk their lives by going deep underground in abandoned mine shafts.

Ilan Godfrey

Ilan Godfrey

Ilan Godfrey

Godfrey’s book documents these and other consequences of mining, building “a visual narrative that provides agency to those whose lives and livelihoods have been destroyed” by government and industry neglect. But Godfrey’s work is also about the resilience of his subjects. Increasingly, miners are standing up for their rights and legal actions have been taken against mining companies. And on a personal level, Godfrey said, he was touched by the generosity of the people he met who helped him with his project.

“It was in many ways a collaborative journey as the people I met helped me make this project possible. They all realized the importance of getting this story out to a wider audience. South Africans invited me into their homes, offered me a hot meal at the end of a long day and a bed to sleep in. I was overwhelmed at the support and kindness of everyone I met on this incredible journey,” he said.

Godfrey’s book, Legacy of the Mine, is available to buy online. You can follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Ilan Godfrey

Ilan Godfrey

Ilan Godfrey