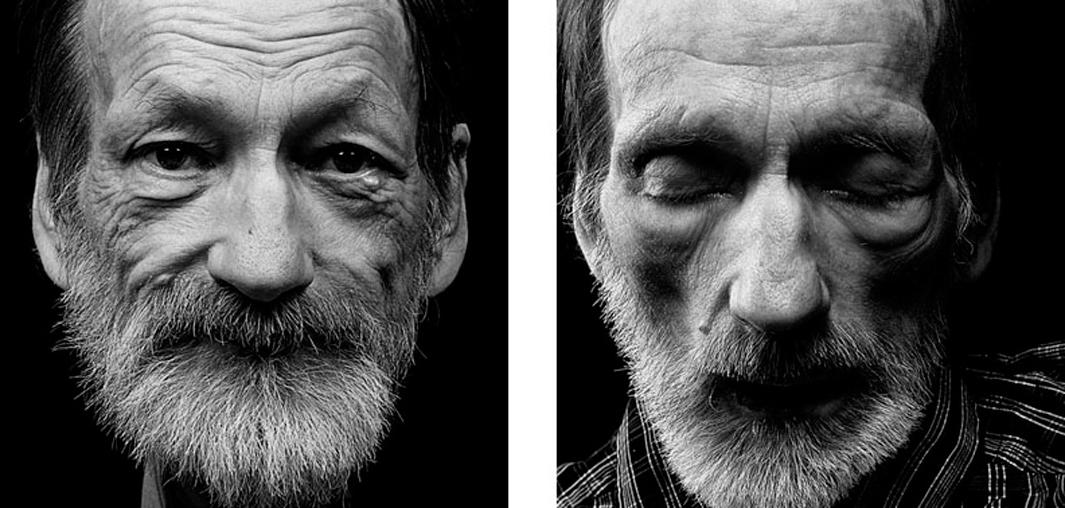

This photo series is about death and contains images of people before and after they’ve died.

As a child growing up in Munich toward the end of World War II, Walter Schels was greatly affected by death, having witnessed the casualties of air raids.

“I was afraid of death and coffins my whole life and I avoided seeing any dead bodies, even those of my parents,” he wrote via email.

Later, when he became a photographer, he worked on a series about birth but was constantly reminded “at the end of this birth will always be death.” He also said that the experience evoked a deep interest in people’s faces, which later influenced his passion for portraiture.

Schels and his wife, the journalist Beate Lakotta, have been together for nearly two decades. Since Lakotta is 30 years his junior, the couple were frightened that, statistically at least, Schels would probably die first, and possibly much earlier, than Lakotta. To face that fear, along with his own fear of death, Schels and Lakotta decided to embark on a series roughly eight years into their relationship titled “Life Before Death.”

Copyright Walter Schels. Text copyright Beate Lakotta

The series consists of 26 people the duo photographed and interviewed while they were ill and near death. They then photographed them a second time, immediately after the subjects passed away.

“I hoped to lose my fear (of death) by doing this project where I had to confront myself with death,” Schels wrote. “I am old enough to think about my own death so it was obvious for me to close the circle between birth and death by doing this project.”

Schels and Lakotta approached various hospices in Hamburg and Berlin in order to find people willing to be photographed. Surprisingly, many people agreed to participate. They worked for a solid year on the project. The time between the first portrait and the second, after the subject had died, could be as short as a few days or as long as a few years. They were on standby 24 hours a day waiting for a call to learn of someone’s death, making it impossible for them to do any work apart from the project.

“We both cried during this time more than ever before,” Schels recalled. “It was impossible for either of us to deal with the physical and, even more, the mental pressure on our own.”

“Even now we still have to fight against our tears when we get touched at certain points.”

Copyright Walter Schels. Text copyright Beate Lakotta

Everyone involved with the project—including the relatives of the subjects—agreed to be photographed (the work was also published as a book). Schels said only a few people decided to stop participating in the project and most relatives were happy to have a portrait of their loved ones after their passing.

Many of the people they photographed were also happy to speak with Schels and Lakotta about their lives and approaching deaths, saying they often had difficulty speaking with friends and family about the realities they were facing. In an interview with the Guardian in 2008, Lakotta spoke about that disconnect:

They had friends and relatives, but those friends and relatives were increasingly distant from them because they were refusing to engage with the reality of the situation. So they’d come in and visit, but they’d talk about how their loved one would soon be feeling better, or how they’d be home soon, or how they’d be back at work in no time. And the dying people were saying to us that this made them feel not only isolated, but also hurt. They felt they were unconnected to the people they most wanted to feel close to, because these people refused to acknowledge the fact that they were dying, and that the end was near.

Copyright Walter Schels. Text copyright Beate Lakotta

Copyright Walter Schels. Text copyright Beate Lakotta

Schels said he decided to shoot in black and white because it focuses more on form and content versus color that often “distracts from the essential part of what I would like to show.”

The goal was to create two equal portraits of the subject; they wanted to preserve a sense of dignity after death. As a result, the pair was forced to move the body into a similar position as the portrait taken while they were alive. In the Guardian article, Lakotta said that was something she never got used to doing.

“It’s like cement,” she said. “That cold, that hard, and that heavy.”

Although the work has been exhibited around the world, Schels said he and Lakotta don’t have a message to share, that they worked on the project to face their own fear of death, something he feels more prepared to face.

“I feel bad about my mortality because I love to live,” he said. “I am full with ideas, only a small part of my photographs have been seen. … I am healthy enough to work and I have a wonderful wife so why should I love death? But death is ruthless. It is better to be prepared.”

Copyright Walter Schels. Text copyright Beate Lakotta