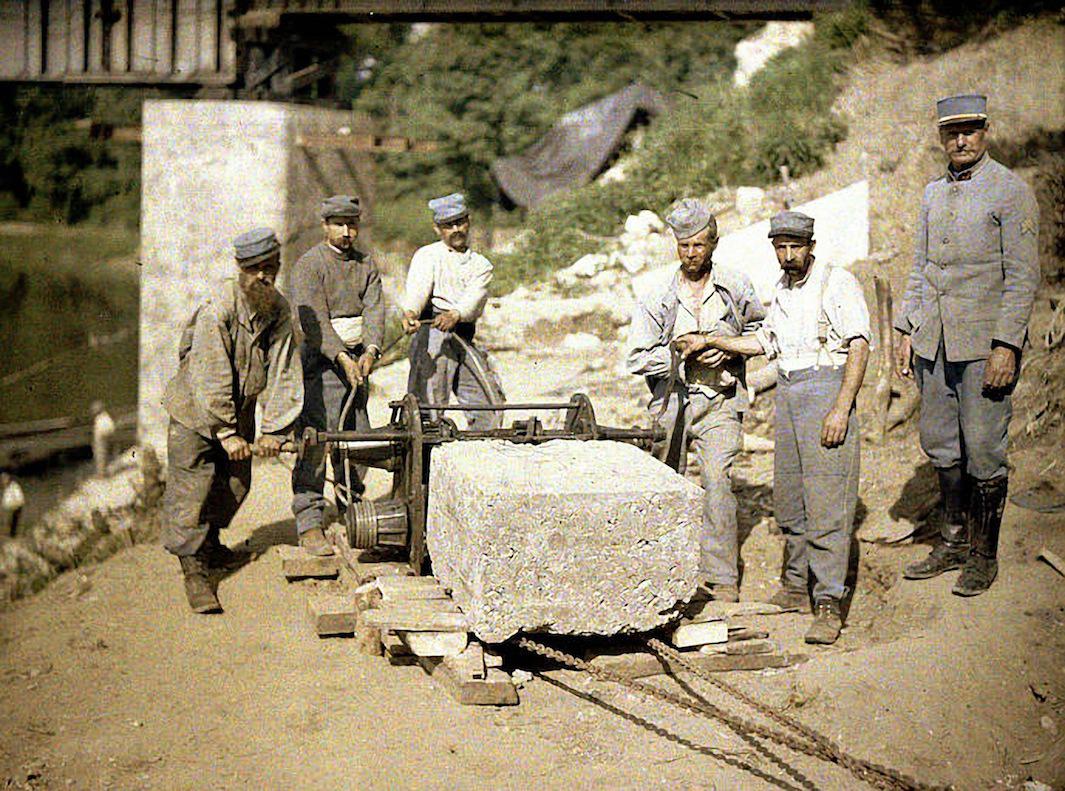

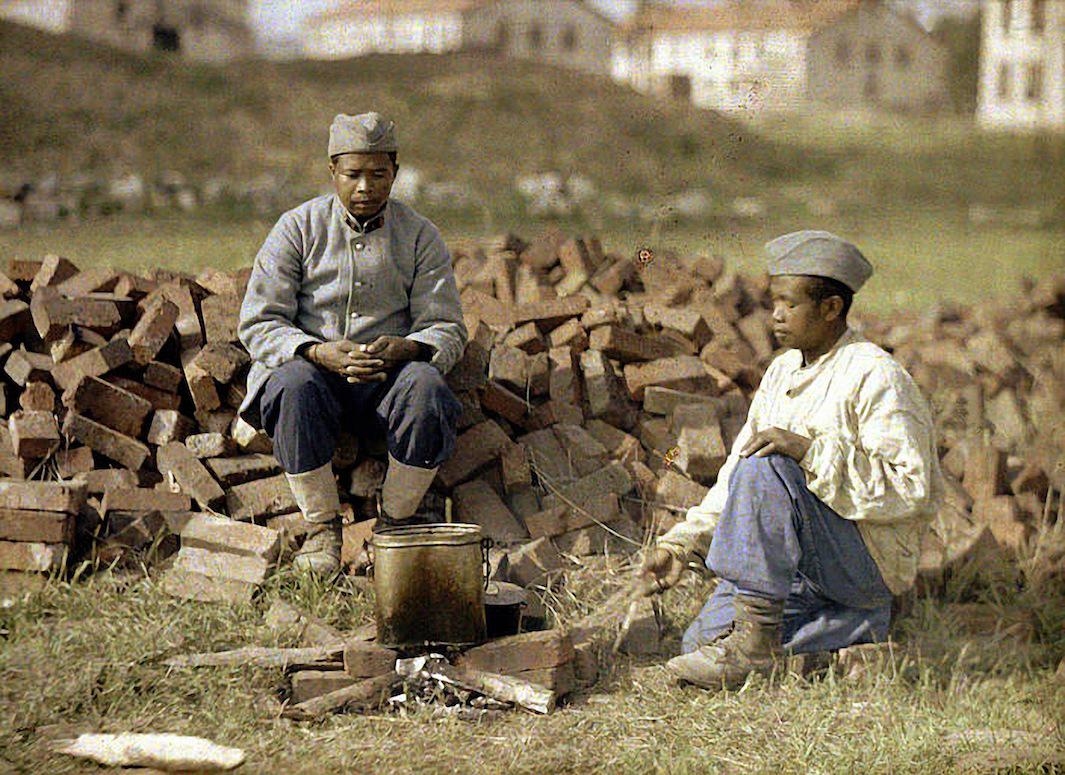

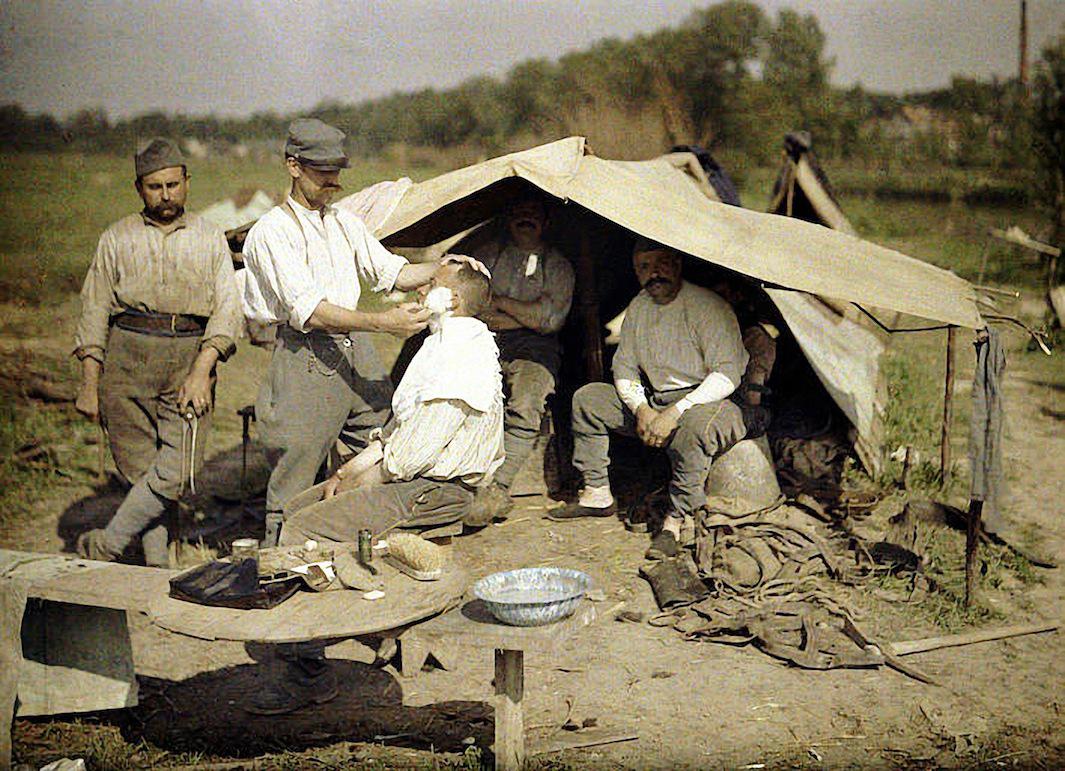

We tend to remember World War I, whose 100th anniversary will be commemorated this month, in black-and-white. But there were a handful of photographers working during the war in color, using an early technology called autochrome that was first introduced in 1907 by the Lumière brothers. Though their hues are not as true to life as color film, the autochrome photos in Getty Images’ Hulton Archive provide a compelling and novel look at the war and those who fought it.

Manufacturing autochrome plates was a complicated process. According to England’s National Media Museum, it required coating the plates in potato starch grains dyed red, green, and blue-violet, then a layer of carbon black (charcoal powder), which filled in gaps between the grains, and then, finally, a panchromatic photographic emulsion. “If you look at one of the images, you can see the tunic was green. The question is, was it actually that hue of green? Was it darker or lighter? I’d be surprised if it was actually spot on because of the nature of the process itself, which wasn’t perfect,” said Matthew Butson, vice president of Getty Images’ Hulton Archive.

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Imags

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

As a result of all the layers, it took a long time for light to come through the plates, so exposure times had to be elongated. Photographers, therefore, couldn’t capture battles in progress. This only amplified the “fairy tale” quality of the images, one already suggested by the photos’ soft, ethereal tones. “Ironically, you don’t see much death or blood or guts in the images. They could have shot static scenes with dead soldiers, but there was very little of that,” Butson said. “It seems to capture more of daily life. This was a different way of looking at the war that didn’t give you much of a feel of the war itself.

The photographs in this gallery are by Fernand Cuville, who served as a photographer in the French army. His photos capture French soldiers in everyday situations, including cleaning their clothes and eating lunch. They also show war’s destruction in scenes of crumbling buildings and ruined landscapes.

According to Butson, it was uncommon to publish color photographs in books or newspapers at the time of the war, so the photographers who used autochrome were only likely able to present those images for lantern slides or lectures. Still, despite the complexity of the process and the relatively little exposure autochrome photos got around the world, Butson said photographers still had good reason for taking them. “Sometimes you do something because it’s difficult and because it’s different from everyone else around you,” he said.

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images