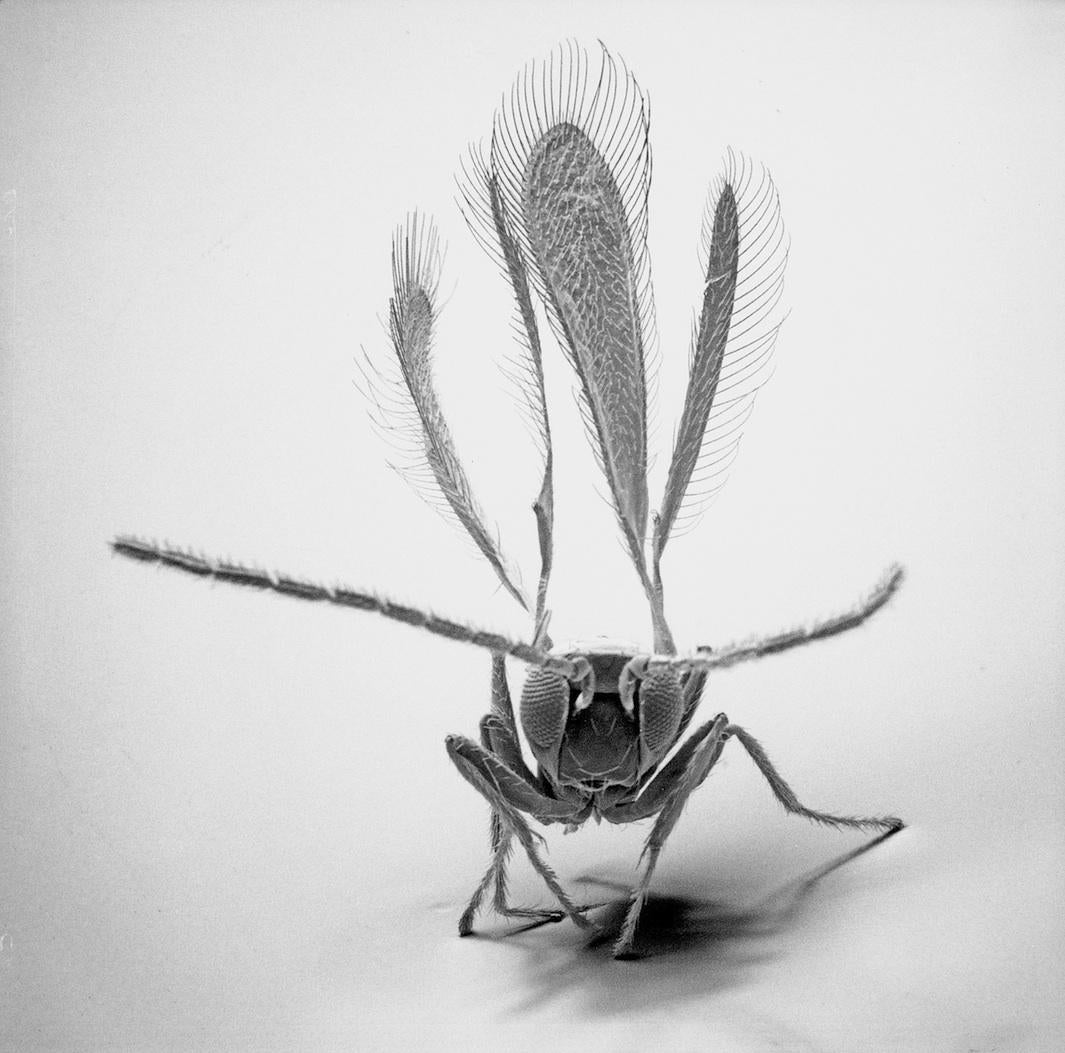

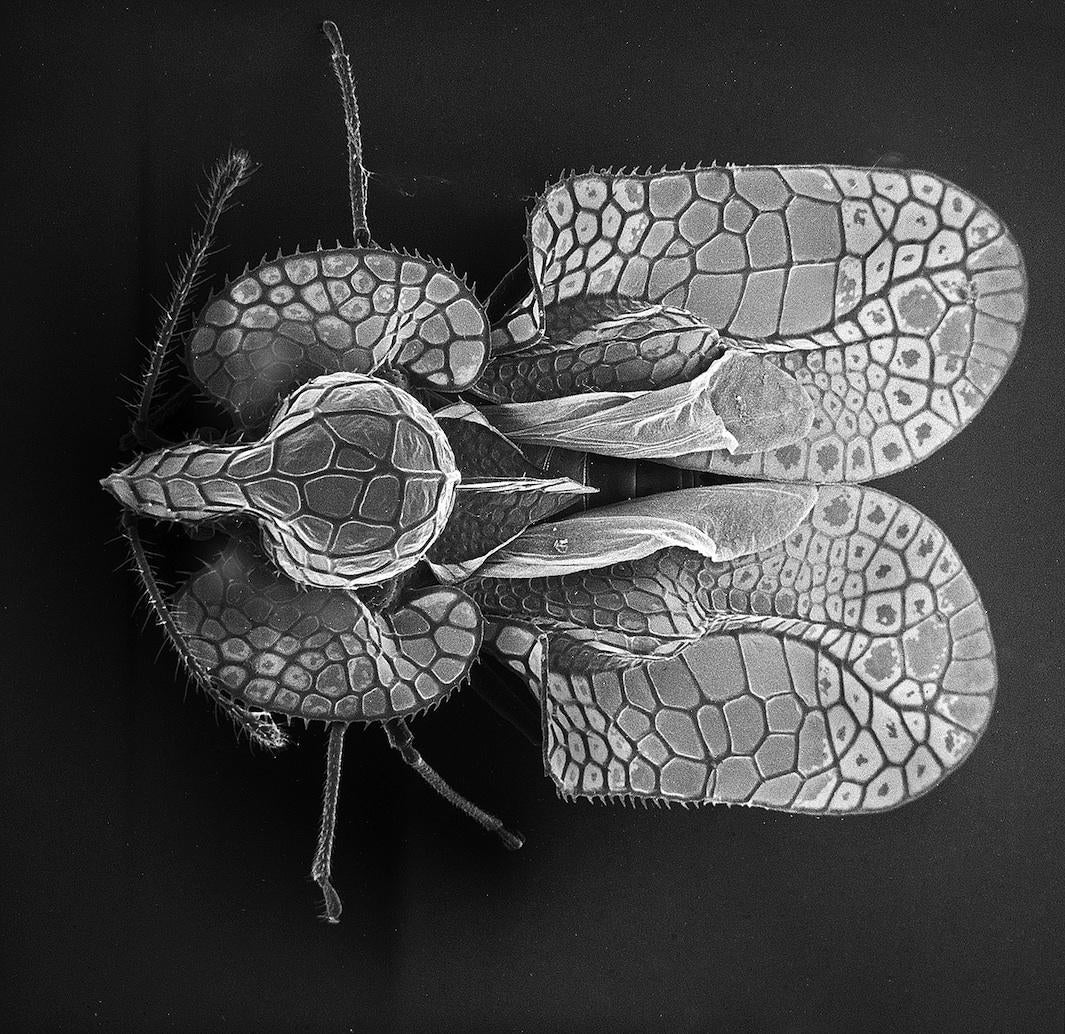

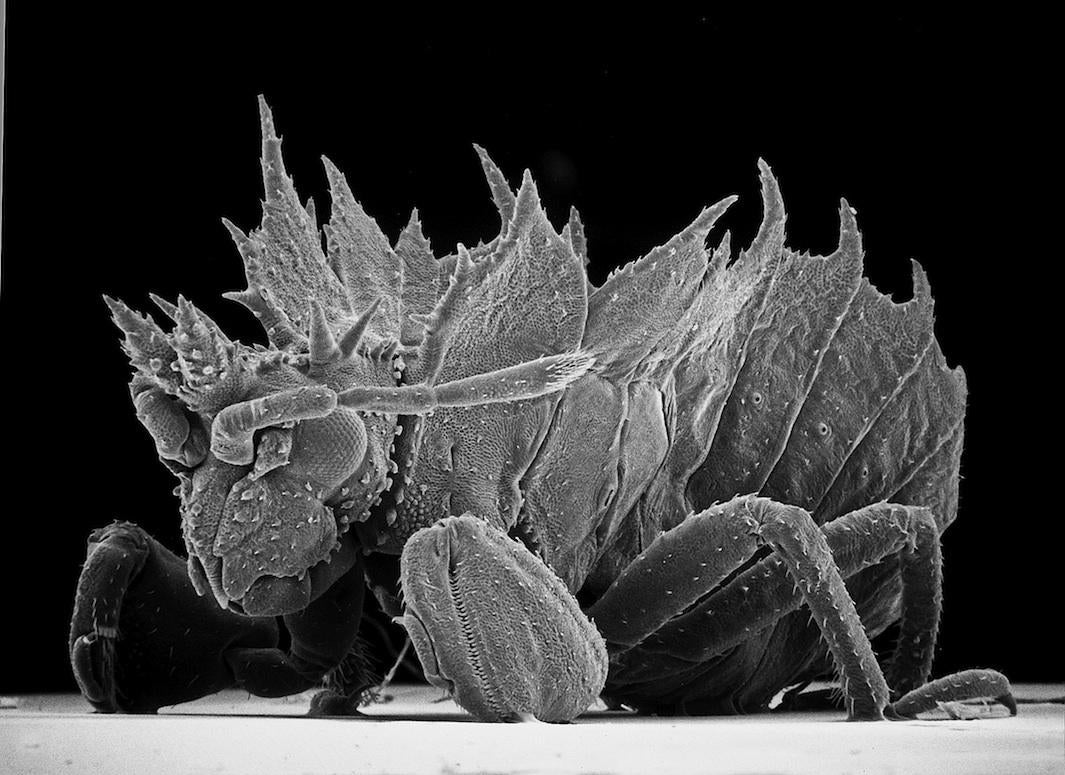

Ever since David M. Phillips took an entomology course at the Boston Museum of Science as a teenager, he’s been hooked on bugs. As a graduate student, he developed a love of microscopes during a course on cell biology. More than two decades ago, when he began working at the Population Council as a scientist studying HIV and AIDS, his interests intersected. Phillips would come into the lab early before work or on the weekends to use the in-house electron microscope to photograph insects. His photographs are now collected in the book, Art and Architecture of Insects.

Electron microscopes aren’t available to many hobby photographers. They can take up a good part of a small room and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. “Using one is a little like flying a spaceship. There are all these buttons knobs and gages,” Phillips said.

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

The microscope scans 3-D objects with a beam of electrons to produce ultra high-resolution images, which can then be photographically recorded. They’re especially good at capturing “surface architecture,” or the bumps and cracks and other textural elements that are characteristic of bugs. “When you look at an insect through a regular camera you can see the relief patterns but not very well. You see the colors more,” Phillips said. “The electron microscope shows a lot of the relief patterns as well as a lot of the detail you couldn’t see in a camera. You can see how the eyes work and how the mouth works much better in many cases than you could with a regular microscope or with a camera.”

When Phillips traveled to scientific conferences, he’d often bring his butterfly net to capture specimens. He’d then preserve them in alcohol. Later, he’d sort through his catch using a dissecting microscope and select the species he wanted. Then, he’d dry it out, arrange it into a lifelike position and coat it with gold so that it would carry electricity.

Phillips was most interested in photographing especially small insects that are too small to see with the human eye and too small to photograph by any other means. “There are bugs called thrips and they live on flowers. If you look at a flower with your eye you can just see some black spots that are moving, but the microscope sees so much detail a little bug like that is no problem,” he said. “I also liked looking at aphids, the bugs that gardeners don’t like because they kill plants. They’re beautiful under the microscope.”

These days, Phillips, now retired, shoots bugs near his house on Cape Cod using his two Nikon cameras—a much different way of seeing the insect world. “I guess I miss the electron microscope but that was then and this is now and I enjoy what I’m doing now. I try to live in the present,” he said. “You can’t bring a two-ton microscope into the field. But you can bring a camera.”

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England

David M. Phillips, courtesy of ForeEdge/University Press of New England