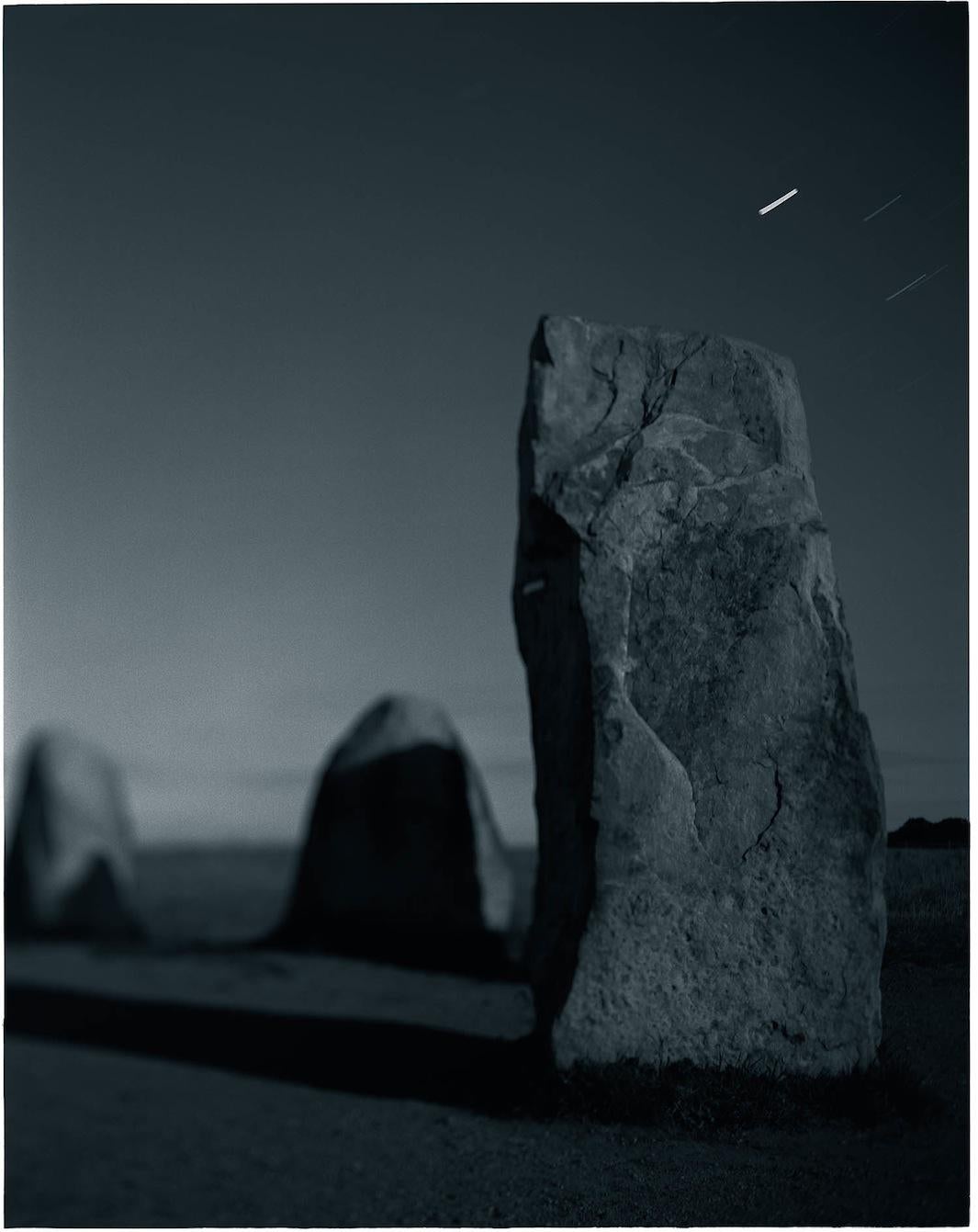

Stonehenge may be the most famous prehistoric monument, but it’s by no means the only one. In 2003, photographer Barbara Yoshida was on a trip to Scotland when she photographed the Ring of Brodgar, a circle of standing stones in the Orkney Islands. She spent the next 10 years photographing lesser-known and rarely photographed megalithic stones in more than 15 countries and on three continents. Her photographs will soon be published in the book, Moon Viewing: Megaliths by Moonlight. “I’m drawn to places that are spiritual and have a depth of mystery, that have a sense of timelessness and history. These stones were obviously set up for ritualistic purposes, and people have continued to interact with them over thousands of years and invested them with meaning and resonance,” Yoshida said. “They have enormous power and a presence that you can feel when you’re among them. We may not know much about the cultures that erected them, but this mystery is what draws me to them. I wanted to record my subjective perceptions and capture some of that mystery.”

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

When Yoshida first began looking into megalithic stones, she found many books on sites in Western Europe. Upon further research, she discovered that there are stones all over the world. Not all of the stones are well documented though, so Yoshida’s travels were frequently a quest into the unknown, requiring expeditions into small villages without maps, and, sometimes, looking for stones based on as little as a tourist’s photograph or word of mouth. Today, many of the stones have been damaged or repurposed. Some have been forgotten, while others have purposely untouched due to superstition. “It was very difficult to tell in advance how photographable they’d be. Would they be freestanding? Would they be next to a house or have trees in the way? Would I find them at all? I might travel thousands of miles and find there wasn’t enough light to shoot,” she said.

It’s not clear exactly how old many of the megaliths are, or for what purpose they were used. Some seem to have served as astrological observatories, others as sites of burial. “I wanted to draw attention to the fact that Neolithic people were not primitive. The more we learn about them, the more skilled, sophisticated, and knowledgeable they appear,” she said.

Yoshida photographed using a 4-by-5 camera, shooting long exposures by the light of the moon from evening until dawn. “My photographs represent time graphically by the use of the star trails. It’s a visual record of how the Earth moved, reinforcing the nation that the stones are a connection between earth and sky,” she said. “We’re not often aware of how much the Earth is turning. It’s a humbling experience to be out at night and realize how small we are on the surface of the earth and how vast the Earth is.”

Moon Viewing: Megaliths by Moonlight will be published by Marquand Books in August.

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida

Barbara Yoshida