Around eight year ago, Frederic Brenner came up with an idea for a photographic project that would recontextualize Israel from multiple perspectives, including his and 11 other photographers.

The idea became “This Place,” a collective photographic look at Israel in the tradition of both the Mission Heliographique in 19th-century France, and the Farm Security Administration’s photography program in the mid 1930s to ’40s.

Brenner had long played around with the idea of home and identity, having spent 25 years working on Diaspora, his worldwide chronicle of Jewish livelihood. “I believe a project undertakes you more than you undertake it,” Brenner said about his work that often involves exploration, examination, as well as serendipity.

To set the tone for “This Place,” Brenner presented a challenge to both himself and the other photographers: Try to see Israel as place and metaphor, one filled with radical otherness, defined by its mix of religions and cultures, where people are often the complete opposite of the person next to them.

“I wanted the photographers to get totally confused,” Brenner said of the project. “I thought of the working hypothesis which is large enough for each artist to reclaim it and define their own working hypothesis within the larger one.”

Ruth Chaya Leonov-Carmely, Nechama Weitman, Pnina Leonov, 2010.

Brenner went to a coffee shop in Jerusalem and noticed the woman on the right. The two met many times and eventually Brenner also came to know both her daughter and mother and took their portrait that not only includes three generations of women but also, in the background, there is furniture they brought from Berlin when the grandmother left in the ’20s. “The photograph is as good as what people are willing to give to you,” Brenner said. “There is always a dialogue … I would like for this book to be a kind of mirror I’m holding up to people to question their own histories and to see their own faultlines.”

Frederic Brenner

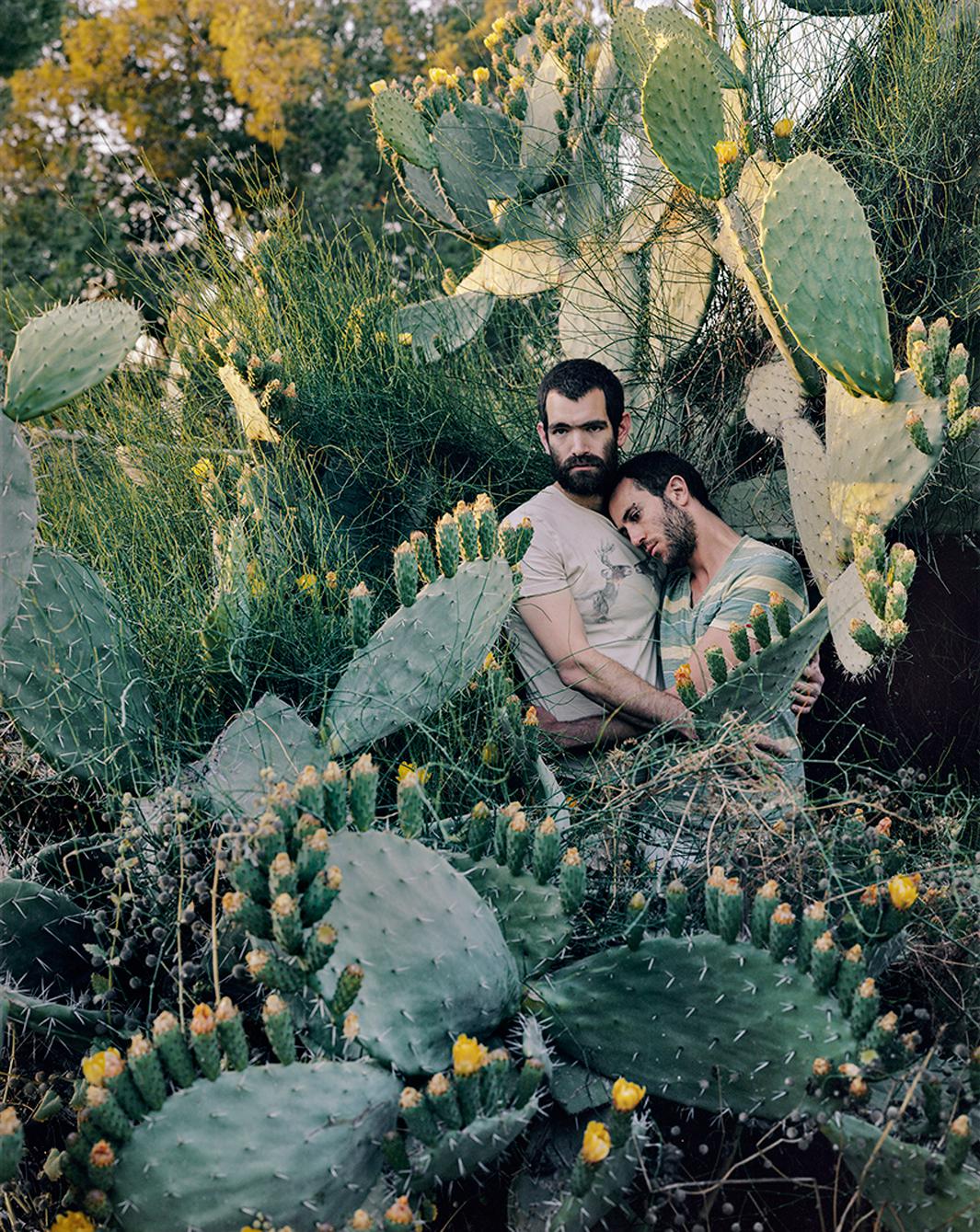

Shlomi and Oren, 2012.

Because Israelies are often nicknamed sabra, or cactus, (hard on the outside, soft on the inside), Brenner was looking for a way to shoot this paradox and initially had the idea of photographing a woman in the middle of the sabras. Brenner said when testing a shot, he has sometimes ended up using the test model instead of the intended model, which was the case for this portrait. “Oren [Brenner’s assistant] was there and he carved a way into the plants. I asked his boyfriend to go in … they were there and I was preparing and it was so beautiful; such an expression of intimacy.” Brenner said each man grew up in a kibbutz—one secular, and the other religious.

Frederic Brenner

“This Place” will be exhibited around the world beginning on Oct. 24 at the DOX Center for Contemporary Art in Prague, and each participating photographer will also publish a monograph of his or her work. In April, Mack published Brenner’s An Archeology of Fear and Desire a collection of mostly portraits that Brenner said is an invitation for the viewer to not only look, examine, and question his portraits of Israel, but, he hopes, also spark a desire for them to look within themselves and begin their own self-exploration.

Menashe Testimony Theater, 2013.

In the north of Israel, children who were 12 years old met with Holocaust survivors to hear their stories over the course of a year. At the end of the year, they put on a play, each one telling the story of the survivor he or she had interviewed. Such strong bonds were formed, that even when, six years later, these youngsters joined the army, they continued to meet with the people they spent the year interviewing. “I was so moved by the incredible humanity that came out of this encounter and I think you can read it in the faces,” Brenner said about the image. “In the most boring kind of environment, you could be anywhere. What brings all these things together? What is this place? What holds it together? I’m sensitive that each of us are woven of so many threads though many don’t match, and this is beautiful. The book is an invitation for people to embrace dissonance.”

Frederic Brenner

He included a wide range of people in the book, but said including diversity is only one layer of what defines Israel, and feels the title is important because he sees all human beings as defined by their relation to both fear and desire.

Brenner purposely didn’t include captions with the photographs because he doesn’t feel providing answers is either possible or productive.

“The viewer is asked to work, there are no resolutions, not for me and not for anyone,” he said about his images. “People will have to wrestle with the ideas of longing, belonging and exclusion.”

Brenner did agree, however, to provide a bit of background about some of the images in An Archeology of Fear and Desire summarized below each image.

Kibbutz Ma’agan Michael, 2012.

Brenner had met with and spoken with many people who had grown up in the kibbutz who, although surrounded by people, felt unloved and abandoned by their parents because they were raised collectively in children’s houses. Brenner said the photograph he decided to include in the book came about when the women spontaneously sat together on the sofa and began a conversation while he observed them. “A photograph is a journey where you know the direction where you want to take the people but you must remember the place where they will take you is always a better place than where you want to take them. The genesis of this photograph is the feeling the women shared with me that they were sacrificed on the altar of a utopian, secular, socialist ideology. They ask, ‘Why did our parents give us away?’ They use the expressions ‘emotional lobotomy’ and ‘eternal longing.’ But none of this comes out in the photograph. What one sees is the women’s vitality and emotional connection.”

Frederic Brenner

Identity Undisclosed, 2011.

I saw a man, maybe 200 meters from me, and I saw a huge scar, he was on the balcony,” Brenner recalled about his first sighting of the man in the portrait. “I went to see him to see about meeting with him and two or three days later I met with him and asked to make a portrait … this photograph is about the fugitive within each of us … all the photographs are made with an 8-by-10 view camera with very little depth of field. I love the people I photograph. Their story is my story, everyone’s story.”

Frederic Brenner

Ben Gurion Airport, 2010.

During a trip from Israel to Paris one year, Brenner happened to see a man he said was wearing “a mask of Zorro” being lead around by another man. Brenner asked him about the extreme facial covering and the man answered that he was learning in a yeshiva (a place of Jewish study) where they were told “It is dangerous to see.” If you look at the photograph, in the suitcase there are blue things hanging out they put in front of their seats on the plane to hide the video screen and any neighboring video screen.

Frederic Brenner

The Awad Family, 2011.

Brenner said he spent time meeting with groups who have been engaged in a process of reconciliation and those fighting for peace, the Circle of Bereaved Parents and the Fighters for Peace, Israelis and Palestinians who have renounced violence and revenge.

Frederic Brenner