Of all the pioneering landscape photographers of the American West, Carleton Watkins was among the earliest and most influential. An exhibition at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, “Carleton Watkins: The Stanford Albums,” includes Watkins’ photographs from the 1860s and ’70s, which present spectacular views of pristine wilderness in the Yosemite Valley and on the Pacific Coast, as well as industrial development in Oregon and along the Columbia River.

Watkins moved west in 1849 during the gold rush and stumbled into a job at a portrait studio in San Francisco. After a few years, he struck out on his own, becoming a specialist in landscape photography when there was little competition and high demand. “If someone was paying him to go to a site he would take those photographs that were commissioned but he would also take some for himself. He was able to build up a stock of images of this gorgeous area that people had only heard about in the news. When those images got to the east his career took off,” said Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell, who co-curated the exhibition.

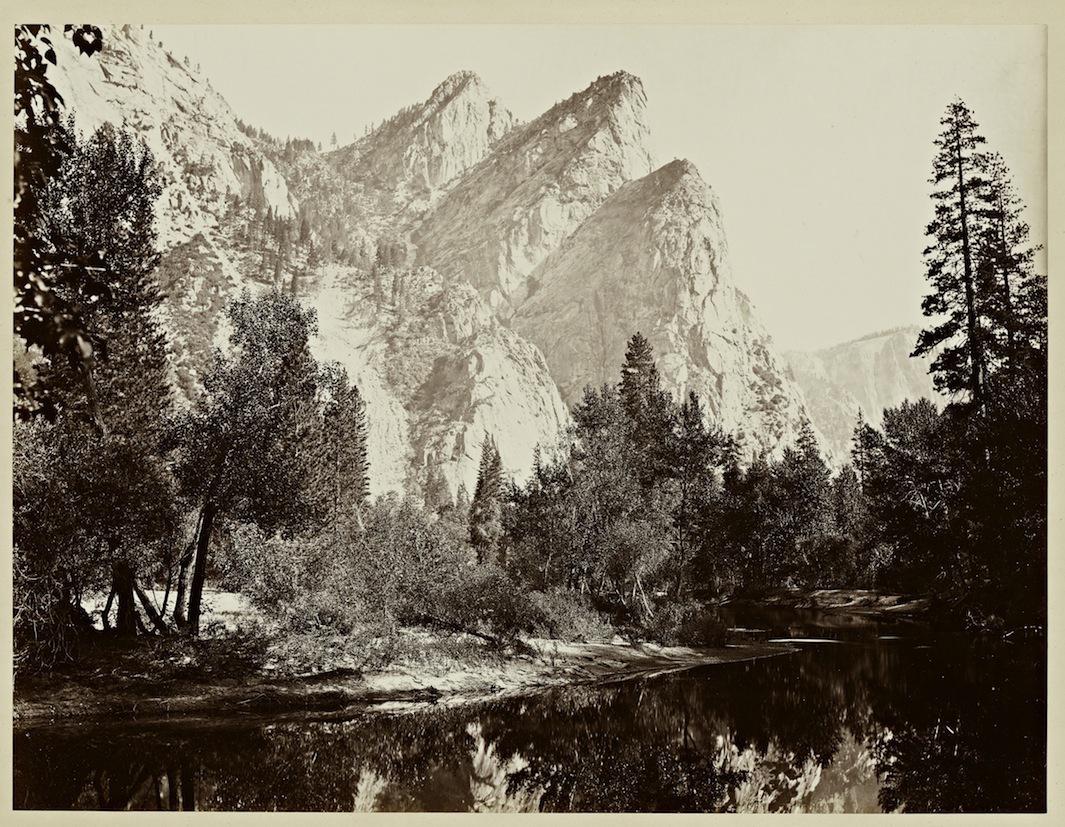

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

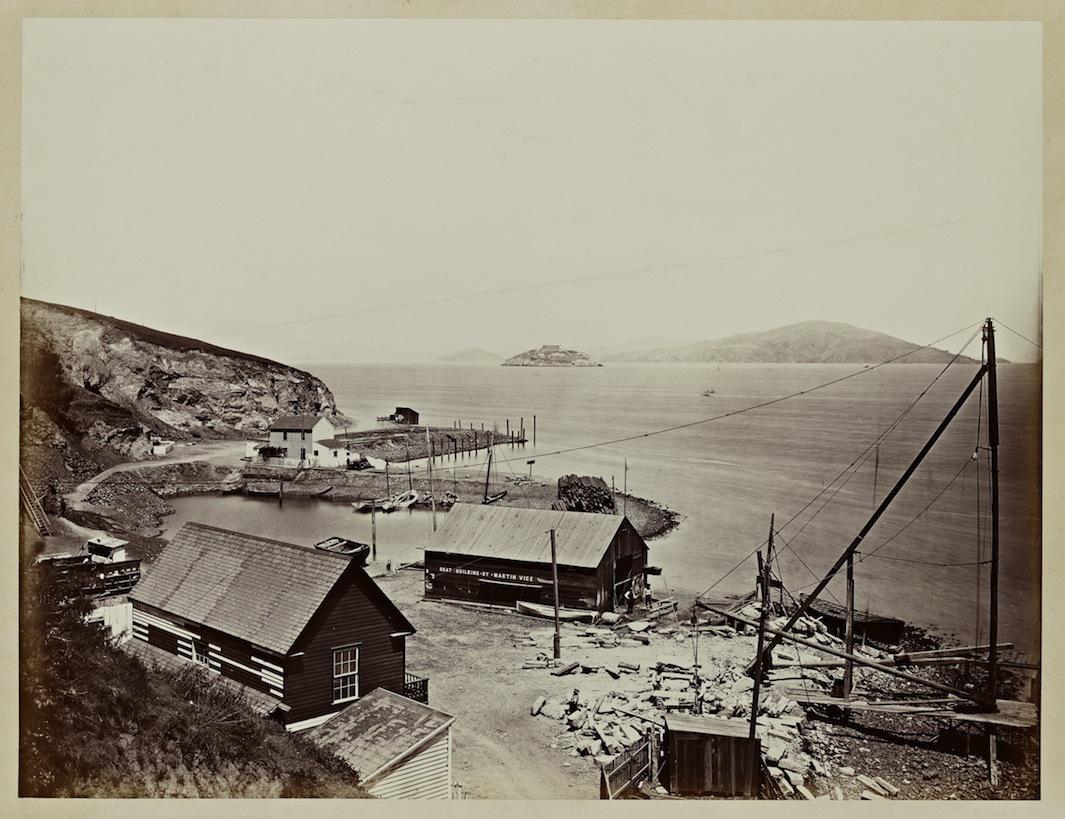

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

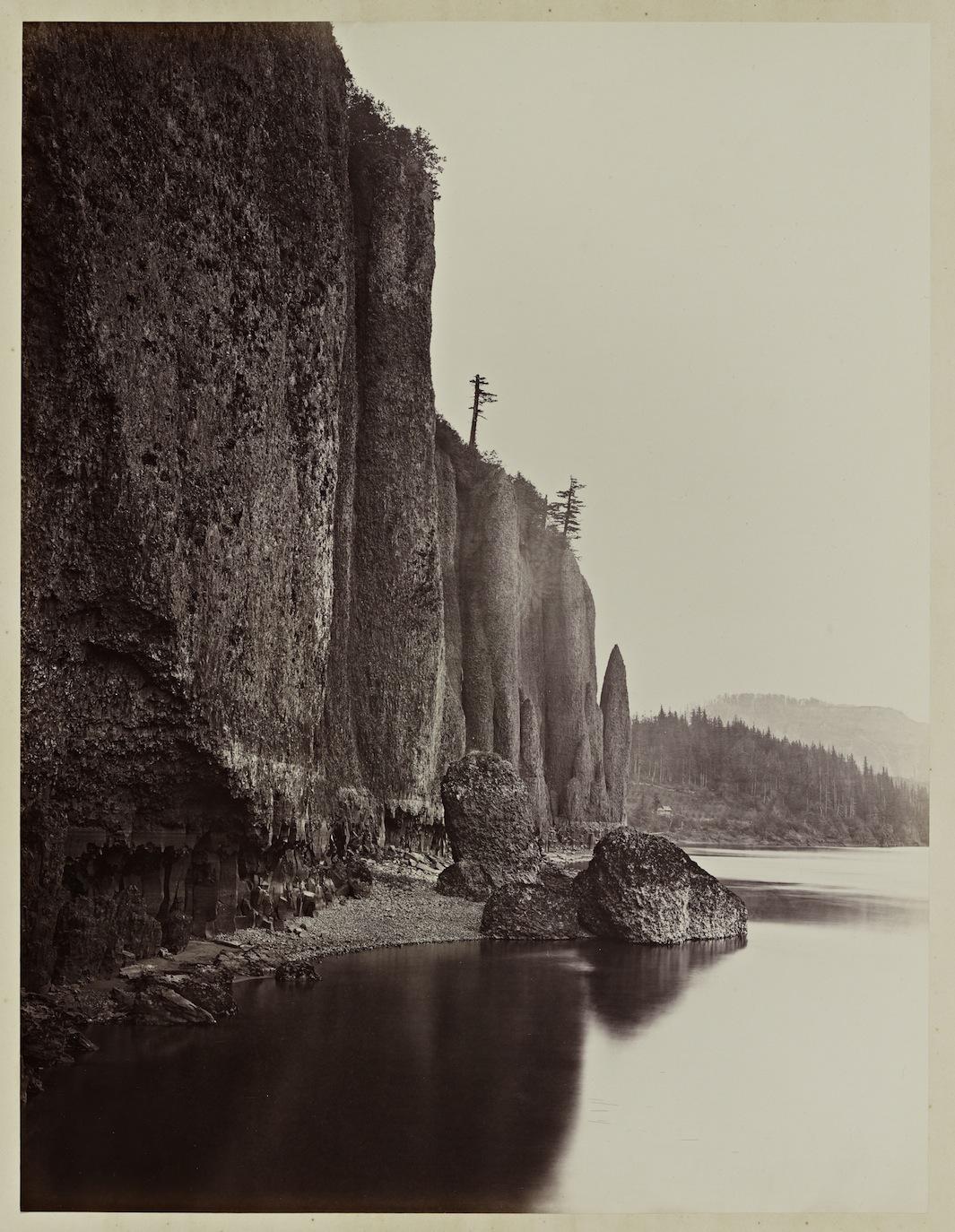

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

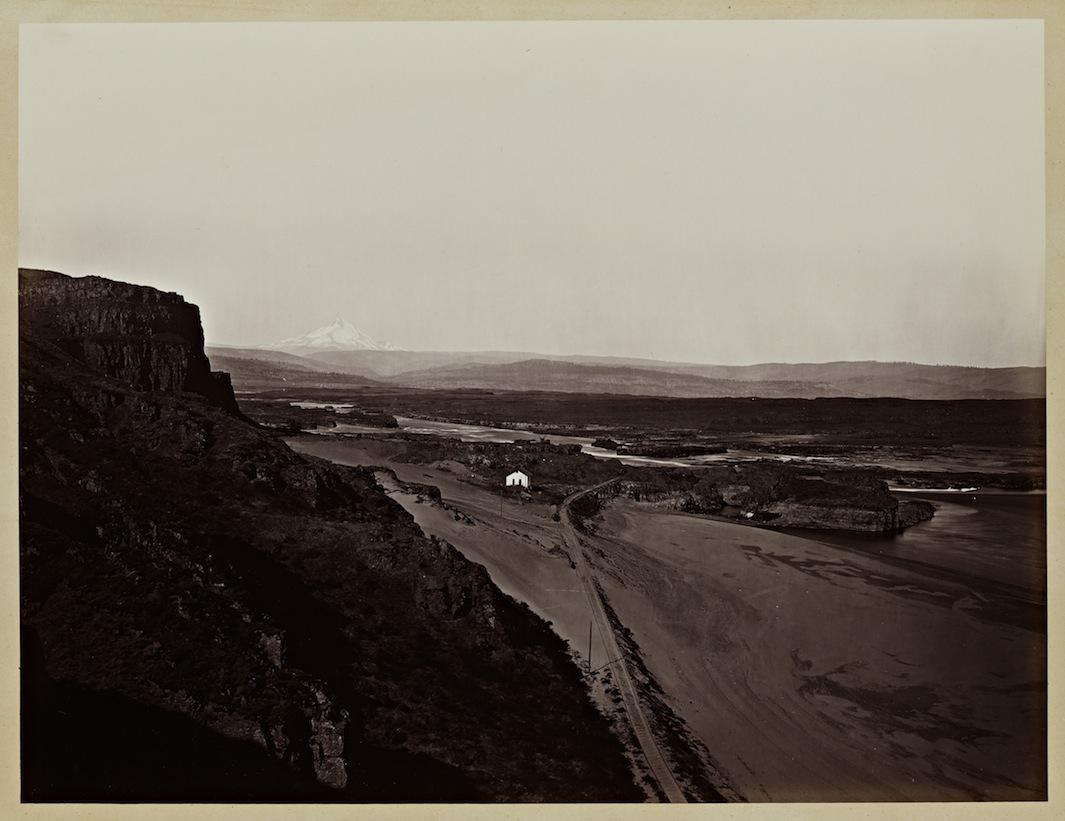

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins,Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

When Watkins traveled, he often took multiple cameras with him, but he was best known for his “mammoth” 18-by-22-inch glass-plate negatives, which he created with a custom-built camera that likely weighed about 75 pounds. “The mammoth plates enabled him to take photographs that would rival small cabinet paintings and lithographs. By working with this larger frame he was able to compete with different forms of visual culture,” she said. “Stereo cards can be an incredible visual experience, but the mammoth plates have this physical gravity to them and they create a completely different context than smaller prints.”

Watkins first went to the Yosemite Valley in 1861, before the tourist industry had truly boomed there. His vision of the area is “completely wild,” free of the traces of man that later photographers like Ansel Adams had to be careful to avoid in their shots. Watkins’ photographs of Yosemite were part of the cultural forces behind Congress’ decision to preserve the land for public use in 1864.* “When you stand in front of one of these mammoth plates, they fill your field of vision. They’re so sharp and rich that you feel you could step into the landscape. The experience of seeing them inspired people to think it was an incredibly special place.”

Watkins’ photographs in Oregon and along the Columbia River, conversely, show lands that were in the midst of drastic changes made by various industries. While these images today might be seen as cautionary, there’s no written record detailing how Watkins felt about the development he witnessed. “Those types of commissions were done to entice investors, not to document or indict a company in wrongdoing. One of the tricky things about us looking at his photos today is that we see those works with a very different filter than what existed at the time,” she said. “Watkins was a working photographer. That’s what you do to survive. You take whatever commissions come your way.”

Photography was still a relatively new medium at the time, and Watkins was an early experimenter. His aesthetic was painterly, and he was known for using environmental conditions like mist and fog to his advantage, and considering natural elements like trees and water as tools for framing. “Watkins certainly pushed the boundaries of photography,” he said. “He was looking at these spaces that were found compositions but it was where he placed his camera that mattered. He was very smart about those decisions. He was thinking about balance and form and looking at the whole picture the way an artist would.”

The exhibition, “Carleton Watkins: The Stanford Albums,” is on view at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center until Aug. 17.

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

*Correction, June 1, 2014: This post orginially misstated that Congress made Yosemite a National Park in 1864. Yosemite wasn’t designated a National Park until 1890. The land was preserved for public use in 1864 through the Yosemite Valley Grant Act.