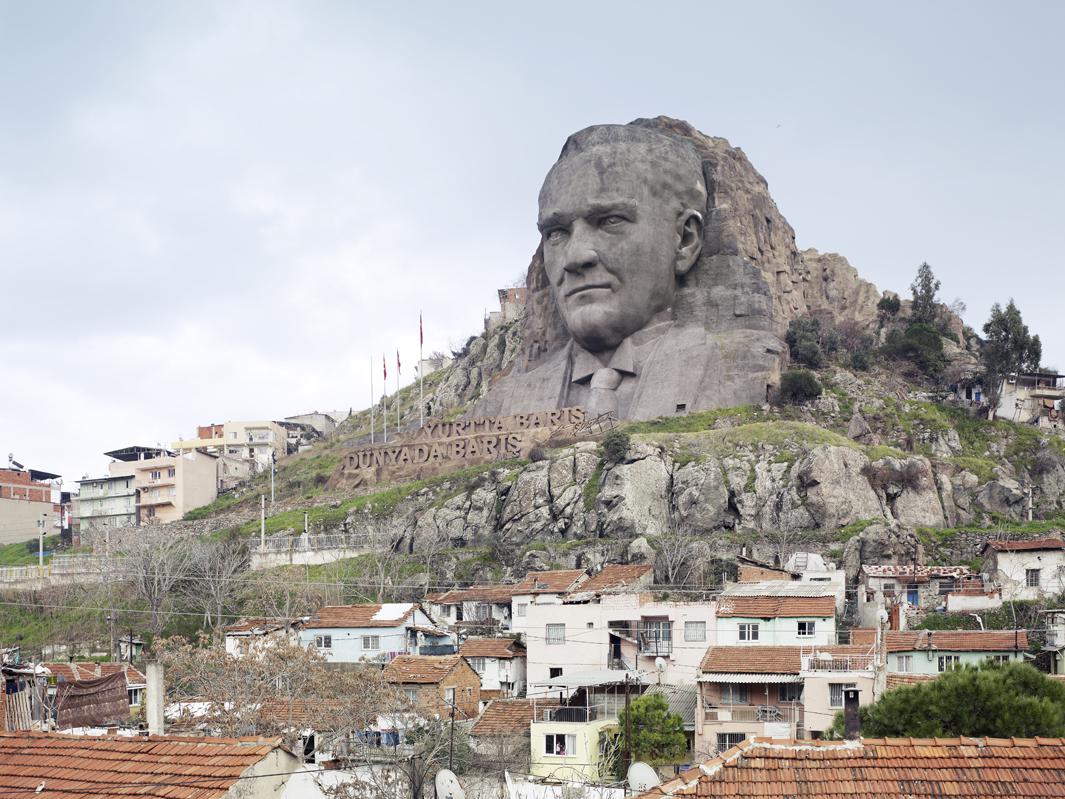

The political, religious, and ideological monuments in photographer Fabrice Fouillet’s series “Colosses” stagger with their extreme dimensions. But Fouillet is not concerned with hugeness for its own sake. He’s more interested in how oversized statues, despite their extraordinary proportions, fit in the landscape around them and, as he writes in LensCulture, the reasons for the “human-sized desire behind these gigantic declarations.”

The humans in Fouillet’s photos—miniscule and appearing infrequently—serve to emphasize the monuments’ sizes. “I wanted human figures in the pictures because by definition the creature and its creator go together. There is also the opposition of the lasting and the living, of the stone and the flesh, of power and vulnerability,” he said via email.

Undoubtedly, many of the humans that appear in the photographs were busy taking their own photos of the monuments. But Fouillet’s images distinguish themselves from those snapshots by capturing the statues away from their designed environments and incorporating them into the larger landscape. “One subject can tell as many stories as there are people photographing it. The most important thing is to find the right point of view, to achieve the expected effect,” he said.

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet

While the largest statues in Fouillet’s series might inspire the most awe, Fouillet often found himself drawn to modestly sized statues, like Christ Blessing in Manado City, Indonesia, because of their style and position in the landscape. Aesthetics aside, Fouillet was intrigued by the context in which each statue was erected. “For example, the African Renaissance Monument in Dakar has set off so many scandals and polemics, between the moment it was designed and its actual achievement, that it might be particularly interesting,” he said.

Another of Fouillet’s series, “Corpus Christi,” focuses on the architecture of places of worship, while “Eurasisme” is a study of Kazakhstan’s capital city, Astana, through its buildings. Architecture, Fouillet said, inspires him. “I feel close to the geometric precision typical of architecture. I am mostly drawn to very elaborate photographs and architecture lends itself well to this type of creations. I also like the fact that it enables us to tend towards more minimal or abstract pictures,” he said.

After a year of traveling, Fouillet still has three monuments left to photograph. The last of which, India’s yet to be completed Statue of Unity, will be the tallest in the world—twice the height of the Statue of Liberty. “I think the proliferation of huge statues from the 1990s on falls within this continued belief in teaching through example. They are typical of an eagerness to teach by using great men and their memory to illustrate important lessons,” Fouillet said.

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet

Fabrice Fouillet