As Brazil prepares to host both the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympic Games, many of the poor communities in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas are being forcibly evicted from their homes as construction in preparation for both events ramps up. The favelas, or slums, have been a part of Rio de Janeiro since the late 1800s and are home to roughly 1.4 million people. Many of the residents don’t understand the legal steps involved in an eviction and have been unable to challenge the government as it removes—and often destroys—their communities.

Photographer Marc Ohrem-Leclef traveled to Rio beginning in early 2012 with a medium-format film camera to document some of the residents of the favelas for a book he titled Olympic Favela. He recently launched a Kickstarter campaign to help finance its publication by Damiani in conjunction with art-book distributor DAP Artbook.

Ohrem-Leclef said he decided to work on the project because he grew more politicized as he got older and he was familiar with Rio and felt a connection to the area. “I thought this idea was the worst thing in the world—people being displaced for an event that is meant to be universally celebrated,” Ohrem-Leclef said.

Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Marc Ohrem-Leclef

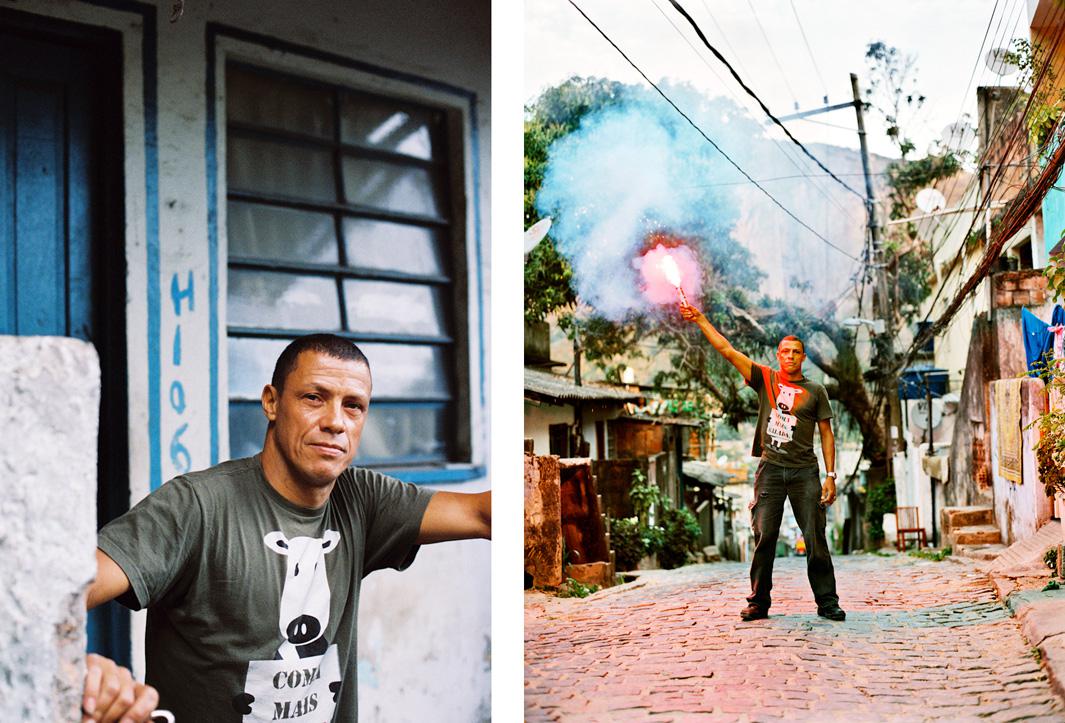

Before his first of two visits to Rio to work on the project in 2012, Ohrem-Leclef spent a significant amount of time researching the area and connecting with NGOs to help him gain access to some of the favela residents. Rather than focus on the actual evictions, Ohrem-Leclef instead decided to use portraiture as a way of highlighting what was happening to the residents. “I was going after a human face rather than a moment of eviction or demolition,” he said. “I wanted to humanize them. Of course they are human, but I wanted to place the residents on the same level as everyone else.”

Through the NGO Catalytic Communities, he was able to meet some of the residents in roughly 13 different communities. He spent a significant amount of time speaking with them about their situations. Ohrem-Leclef also wanted to represent the fighting spirit of the residents and began researching historical images and iconography that had portrayed the idea of a rebellious spirit. Through Image Atlas, he began searching for images that represented liberation, resistance, and liberty. He found inspiration from Eugene Delacorix’s Liberty Leading the People to the Statue of Liberty. There was a common thread found in most of the images: an arm raised, often holding a flag or torch. Ohrem-Leclef appropriated that symbol through the use of a flare, which he had many of his subjects hold aloft. It was a perfect symbolic mix between their individual spirits and that of the Olympics.

Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Marc Ohrem-Leclef

During an interview with Mazie M. Harris (who helped Ohrem-Leclef with the editing process) that was done in conjunction with the book, Ohrem-Leclef discussed that idea. “It all came back to very basic gestures, and the torch as a prop plays beautifully on both sides of the spectrum: emergency and celebration, resistance and liberation,” he said.

Although he could have spent more time working on the project, Ohrem-Leclef said he felt an urgency to publish the book since it was clearly a time-sensitive project and one that he hopes raises awareness about what is happening to these people. It has clearly touched him. “My heart is with the people in this city who are being displaced,” he said.

Marc Ohrem-Leclef