When Aaron Huey first visited South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation in 2005, he didn’t expect that it would be a world-altering experience. He began the project as an objective photojournalist’s look at poverty in America. But after spending eight years documenting the residents of Pine Ridge, his professional and personal outlook has changed dramatically.

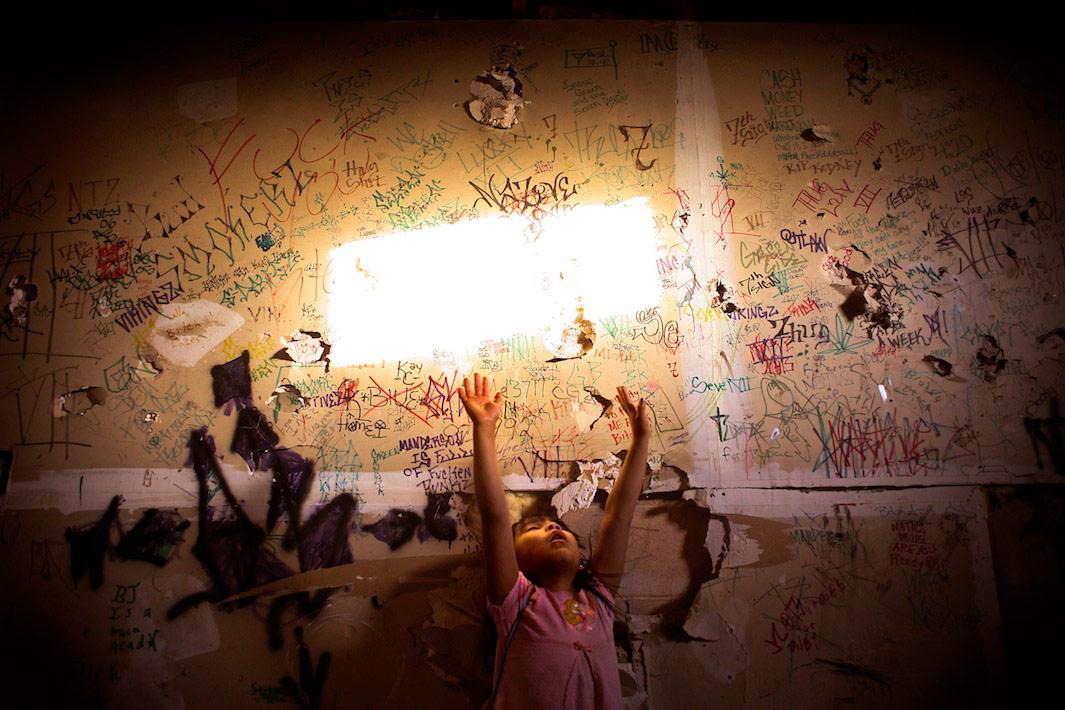

Before Huey arrived at Pine Ridge, all he knew about the Oglala Lakota tribe were the statistics: a startlingly low life expectancy along with a startlingly high rate of unemployment, poverty, violence, and infant mortality. Once Huey became embedded in the community and started talking to the people there, he knew the mechanisms of traditional journalism wouldn’t suffice to do the type of work he wanted to do with the Lakota people. “People there were telling me the most epic stories I’d ever heard, and people were talking about a history of genocide. I knew that word would never be used in the mainstream press. I knew right away I wasn’t OK with that, that I wanted a bigger piece of the truth than just more statistics and more pictures of poverty,” he said.

Aaron Huey

Aaron Huey

Aaron Huey

Huey’s talk at TEDxDU in Denver in 2010, which presented a history of Lakota relations with the United States government alongside his photographs, represented the first in a series of steps toward a larger commitment to the Lakota and a personal shift away from the observational perspective often associated with photojournalism. “For the first several years at Pine Ridge, I didn’t really get it. I knew [their stories were] more than statistics, but I didn’t know what I was supposed to do with it,” Huey said. “It was really dark and hard to process, and I kept giving up over and over again but then getting sucked back in.”

“[Life there] is just too hard; it’s the saddest and scariest thing I’d seen on the face of the Earth. But I loved the people and the families I became a part of, and I think over time I learned how to hear them,” he said. “It took four years to figure out what I was doing. The Ted talk was the moment where I chose a side. I didn’t do the Ted talk as a journalist; I did it as an advocate. I did a Ted talk about a history I knew magazines wouldn’t run.”

Aaron Huey

Aaron Huey

Aaron Huey

Since then, Huey’s extensive work on the subject has included a National Geographic cover story about Pine Ridge, a street art collaboration with Shepard Fairey and Ernesto Yerena, a storytelling project, and a nonprofit organization called Honor the Treaties that funds collaborations between Native American artists and Native American advocacy groups. His book, Mitakuye Oyasin, which was published by Radius Books in July, is perhaps just the tip of the iceberg of Huey’s work with the Lakota. “The whole book was almost more like a prayer or a poem than a documentary. It was like a ceremony, and I didn’t realize it until the end. I didn’t experience that place in a linear way and, at the end of the day, I didn’t want to put it together in that way,” Huey said. “It’s a big stack of images that a lot of people wish there was more explanation for and I didn’t want to give it. I didn’t want to walk everybody through every image.”

Huey has now moved on to other National Geographic features, but he says his experience at Pine Ridge has forever shaped the way he works. “I think that it taught me I will never be satisfied as just an impartial witness, as a person who just goes and does a story,” Huey said. “I want do stories about communities I care about, stories that have the ability to make a real impact, and so I’m only investing my time after Pine Ridge in stories that really matter, stories that have heart.”

Aaron Huey

Aaron Huey