An Uncensored Look at the Real Sochi

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery. All images from The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus (Aperture, 2013).

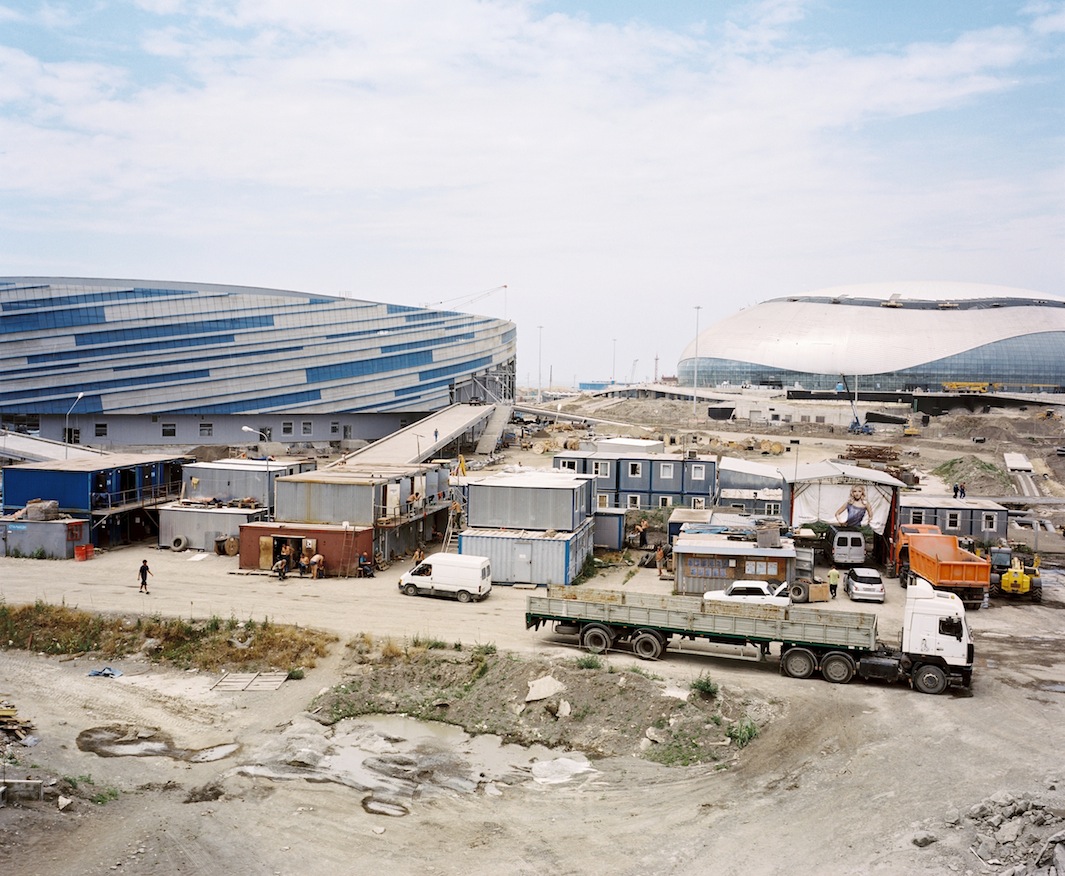

With the 2014 Winter Olympic Games kicking off this week, the world will get a fast and likely incomplete introduction to Sochi, Russia. But for Dutch photographer Rob Hornstra and journalist Arnold van Bruggen, Sochi is familiar territory. They’ve spent the past five years painstakingly reporting on Sochi and the surrounding region, determined to transcend the Olympic glow that now engulfs the city. A look at their expansive work, “The Sochi Project,” fills in the blanks of the city’s story, revealing an incredibly complicated place steeped in history and conflict. “We don't have anything against these games, but we hope if you watch them that you know in general where it's taking place,” Hornstra said. “If you look a little bit farther than the stadium, you'll see different things. I think it's important for people to know what's going on over there, that it is part of this facade, the Putin show.”

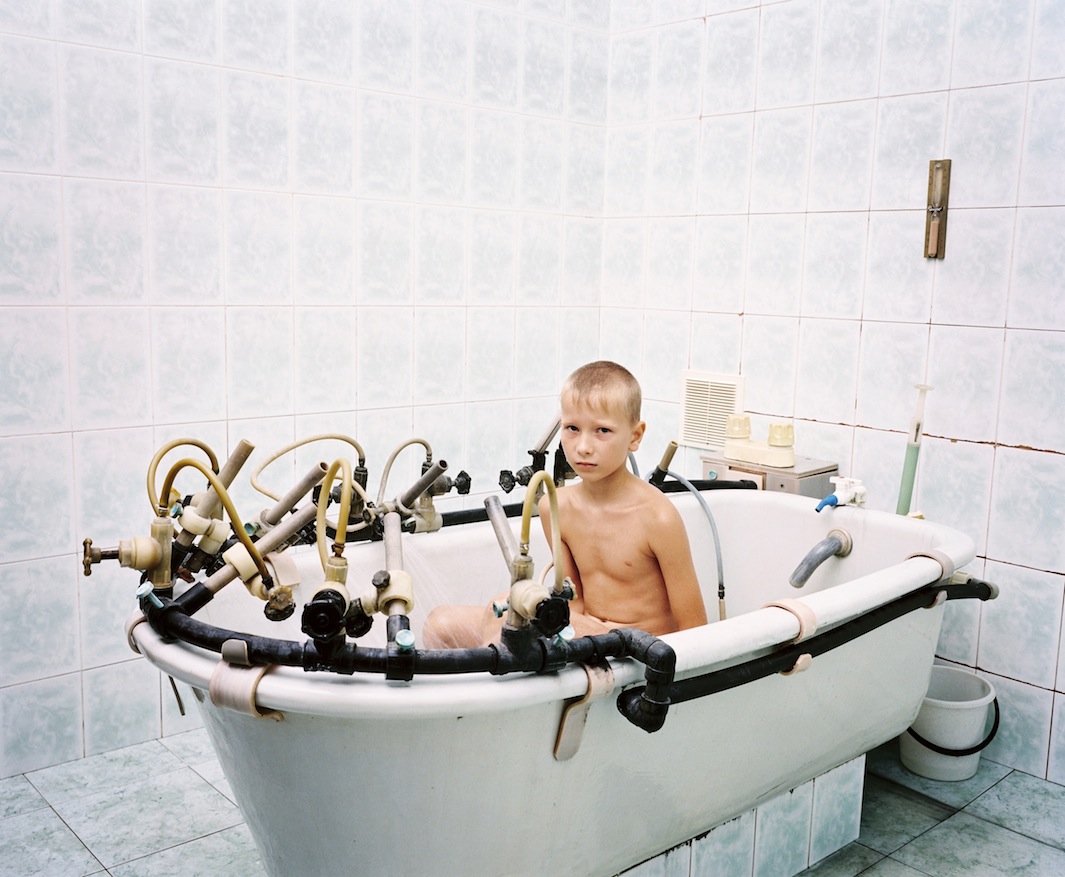

The work tells the story of Russia’s summer capital, “the Florida of Russia, but cheaper,” including its history as the site of a genocide, its development into a tourist destination, and recent changes made in anticipation of the Olympic Games. “It's Putin's project. The people there, they don't care about these games. They were complaining about too much traffic, dust, and construction work,” Hornstra said.

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

It also follows the history of nearby Abkhazia, which declared itself an independent country in 1999 but is only recognized by five nations, including Russia. Russia and Georgia fought a war over Abkhazia in 2008, and it is unclear how the games will affect relations between the nations. The work also documents the nearby North Caucasus, a poor and violent region in Russia that has produced terrorism and female suicide bombers.

Hornstra and van Bruggen’s mission was ambitious, and from the beginning the pair knew that their reporting would eventually clash with the interests of the Russian government. “We were constantly covered by Russian authorities and the secret service. The more we got into the stories and the material, the more difficult they become, the more difficult it was to handle this situation. We were arrested multiple times in the North Caucasus,” Hornstra said.

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Recently, Hornstra and van Bruggen were denied visas to re-enter Russia, which resulted in the cancellation of an exhibition planned in Moscow and the end of their work on the project. “I don't care so much about the games. I care about Russia. I've been working there for 10 years. I have a lot of friends out there,” Hornstra said. “We want to follow up on specific main characters in the project. We want to see how the region around Sochi is dealing after the games, how it's developing after the games. It's really a pity that we can't go back.”

Hornstra’s photographs can be seen in the book The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus. They will also be on display at the DePaul Art Museum through March 23.

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery

Rob Hornstra/Flatland Gallery