Forty years after the death of Life magazine photojournalist Eliot Elisofon, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art is celebrating the legacy of the photographer who offered an extensive look at post–World War II Africa over several decades. “If you look at the history of how Africa was represented in photography in the 20th century, you’d would be hard pressed to find someone who was more prolific in shooting photographs of Africa and had more of an impact than Elisofon,” said Amy Staples, the curator of “Africa ReViewed: The Photographic Legacy of Eliot Elisofon.”

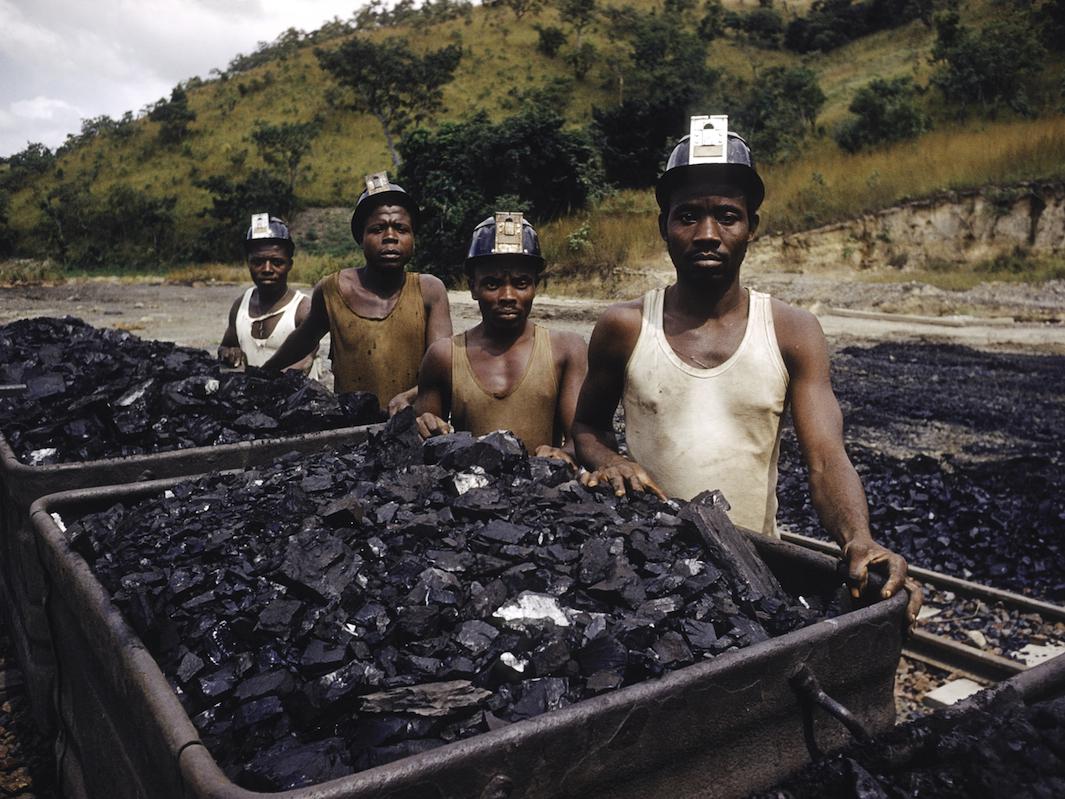

Elisofon went on 11 trips to the continent, including a tour as a war photographer in which he accompanied Gen. George Patton through North Africa and a four-month trip from Cape Town, South Africa, to Cairo in 1947 that culminated in a Life cover story. Elisofon’s images are significant for the way they helped change American perceptions of Africa in the 20th century, which had for the most part been informed by inaccurate literary and film representations. “He was looking for authenticity and despised these films like Tarzan and safari films. He really felt they were a disservice,” Staples said. “He wanted to illuminate what he considered to be the richness and the dignity and the beauty of African culture and society.”

Eliot Elisofon

Eliot Elisofon

His photos also offer important glimpses into the production of African art. “One of his big desires was to help people understand what these artifacts meant to Africans themselves and how they’re used and performed, their symbolic meanings, and their cultural significance,” Staples said.

Elisofon was a collector of art and brought back more than 700 objects from Africa during the course of his life. These objects are part of the museum’s exhibition, as well as some of Elisofon’s photographs of them. “The large details and multiple views of the objects highlight their beauty,” Staples said. “Where previously they might have been thought of like anthropological artifacts, he helped people see the work as artistic and abstract forms.”

Eliot Elisofon

Elisofon brought an artistic sensibility to his photojournalism, which can be seen in his most epic landscapes to his smallest natural subjects. “If he was photographing a rainbow in the Congo, he’d use filters to make it more dramatic. His photographs of the landscapes and the architecture are really monumental. But you also have him photographing dragonflies or insects. It can get almost microscopic,” Staples said.

“Africa ReViewed: The Photographic Legacy of Eliot Elisofon,” is on view at Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., through Aug. 24.

Eliot Elisofon

Eliot Elisofon

Eliot Elisofon

Eliot Elisofon

Eliot Elisofon