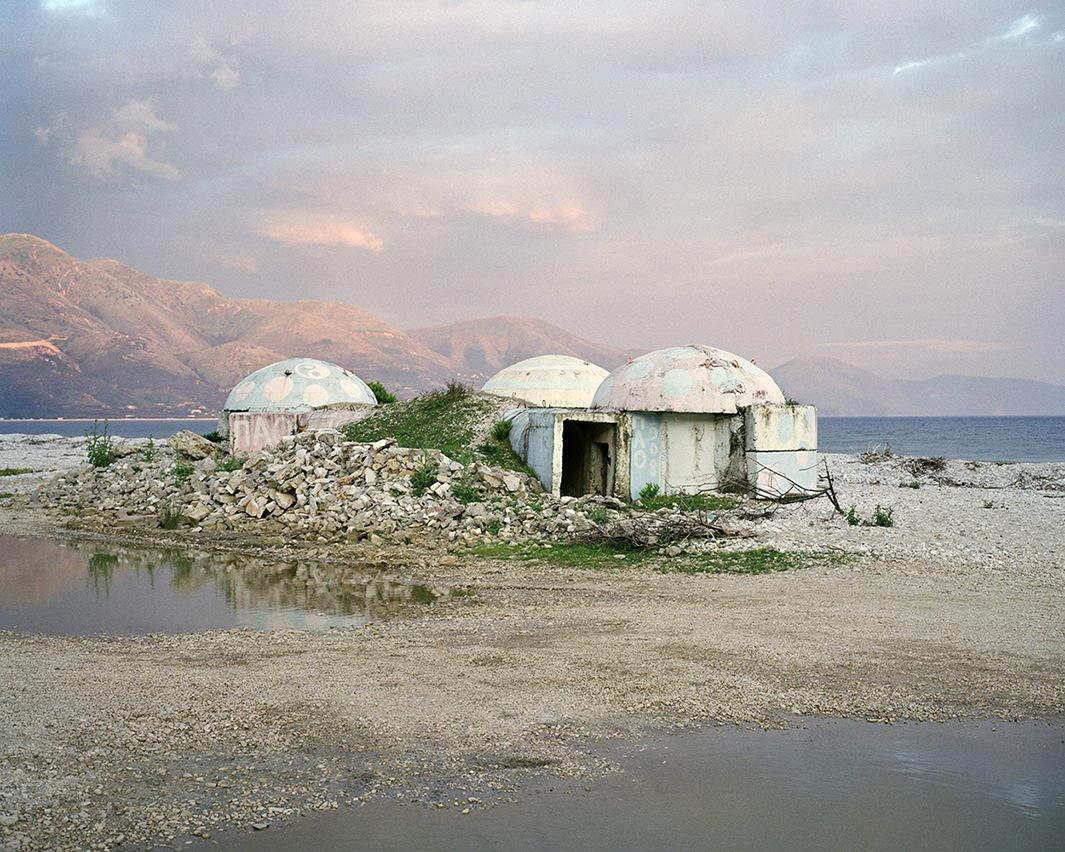

In Albania today, one bunker stands for every four people who live there. Built during Stalinist Enver Hoxha’s 40-year rule, the more than 700,000 above-ground bunkers dotting the landscape were never used to defend against attack, as intended. Now, they serve as a stark reminder of the Hoxha’s dictatorial reign.

Photographer David Galjaard was working on a series on Cold War bunkers in the Netherlands in 2008 when a fellow journalist told him about the bunkers in Albania. After some initial research, Galjaard knew he had to travel to Albania to see the bunkers for himself. “The intention was to find out what the consequences of these bunkers are for the Albanian landscape, and what it meant for its people, their collective memory, to be continuously triggered by these pill boxes, being reminded of their fierce dictatorial past,” Galjaard said via email.

After Galjaard’s first trip, he knew there was a bigger and more interesting story to be told than he originally intended. “In October 2009 I went back. During this trip I decided to use the bunkers as a metaphor for documenting a country in transition. At that point it became not a story about bunkers, but a story about the history, present and future of Albania,” Galjaard said.

Galjaard made three trips to Albania over two years and spent more than four months in the country altogether. Since the bunkers are not mapped, Galjaard drove in a small van at random hoping to bump into them. When he got to mountains and beaches, he traveled on foot.

Today, Galjaard said, many of the bunkers are empty or repurposed. They are used as storage for hay or as animal sheds. Some people have opened small shops or restaurants in them. One man Galjaard met transformed a bunker into a tattoo studio. There is even a music festival that makes use of the bunkers. Many of the bunkers that haven’t been revitalized have been at the mercy of the elements. Others have been destroyed for their iron.

Generally, Galjaard said, Albanians have mixed feelings about the bunkers. Some people would like to keep them as monuments, while others would like to have them removed because they make it difficult to work the land. “Most Albanians are not interested in the bunkers. As one of the poorest countries in Europe they have more urgent matters to worry about. It’s the future they’re interested in, not the past,” Galjaard said.

Foreigners visiting the country, Galjaard said, are often surprised to learn about the bunkers and delight in picking them out of the landscape like Easter eggs. Albanians have thought of some interesting ideas to leverage tourist interest, but Galjaard said there remains room for innovation. “Once the economy of the country picks up a bit and more tourists visit, I think Albanians will have a clearer image of the potential of the bunkers as an touristic attraction. It is time that they are finally used to benefit the people,” Galjaard said.

Galjaard’s photos are collected in the book Concresco.