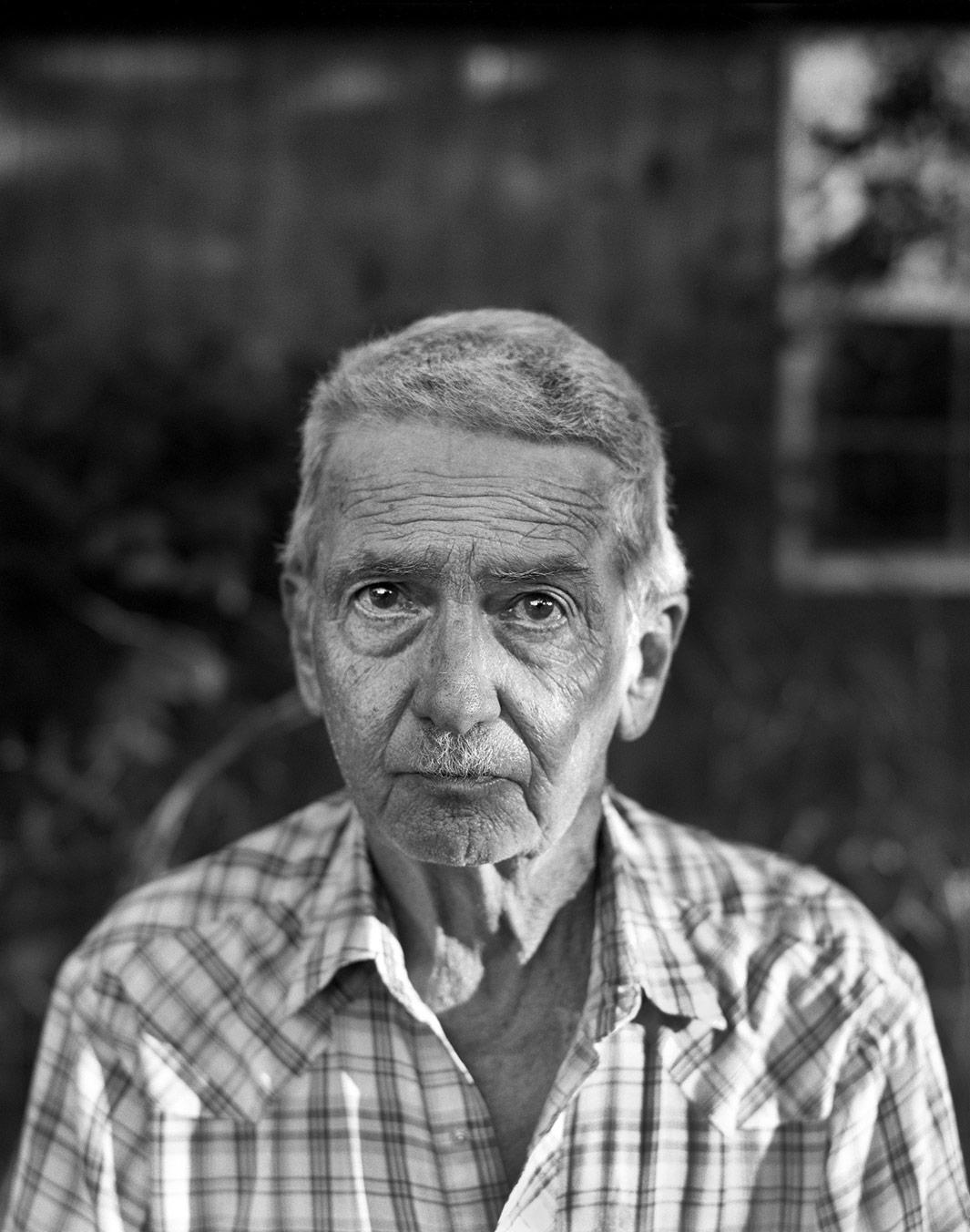

As a child, photographer Eugene Ellenberg had a hard time separating his father from the favorite chair in which he often sat. Later in life, during breaks home from college, Ellenberg discovered napkins, used almost like stationery, upon which his father often scribbled notes, typically Elvis Presley song titles. Both inanimate objects offered glimpses into the quiet nature of Ellenberg’s father, and although the two shared the same name, and facts were known about the elder Ellenberg—a Vietnam veteran who enlisted in the Army when he was 16—the photographer Ellenberg never felt he truly knew or understood his father. Beginning in 2010, he decided to try to understand both his father and his family (who all share a reserved nature) and began to photograph them for a project that would eventually record the end of his father’s life.

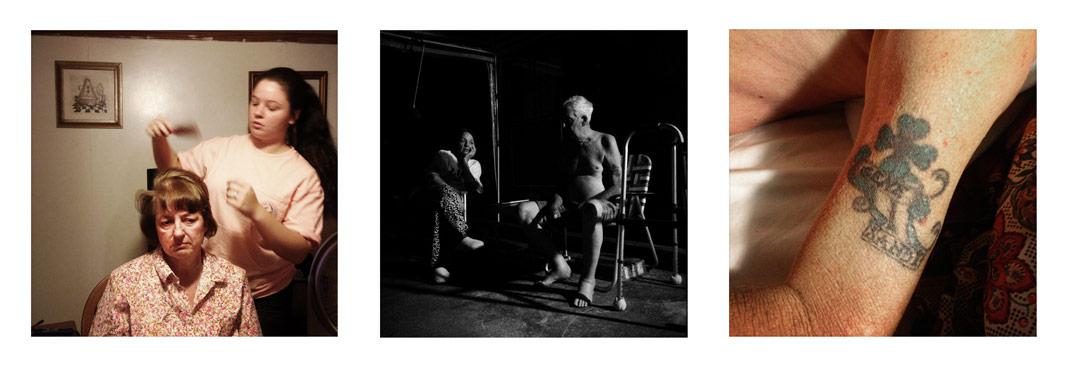

Much of Ellenberg’s series, “In My Father’s House,” deals with the concept of Ellenberg’s memory of his family and his method for trying to better understand their relationships, as well as attempting to understand exactly who they all are. He elected to have his photographic equipment follow the lead of whatever emotion he tapped into while taking photographs, choosing a mix of equipment and processes throughout the series.

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

When Ellenberg began “In My Father’s House,” one of the first images he took, titled Close from 2010, was of his father in his chair. “That chair was both his throne and that which constrained him,” Ellenberg said. “I remember removing his boots from his swollen feet for him night after night. That was a proud moment for me as a son, a simple gesture but something shared between us.”

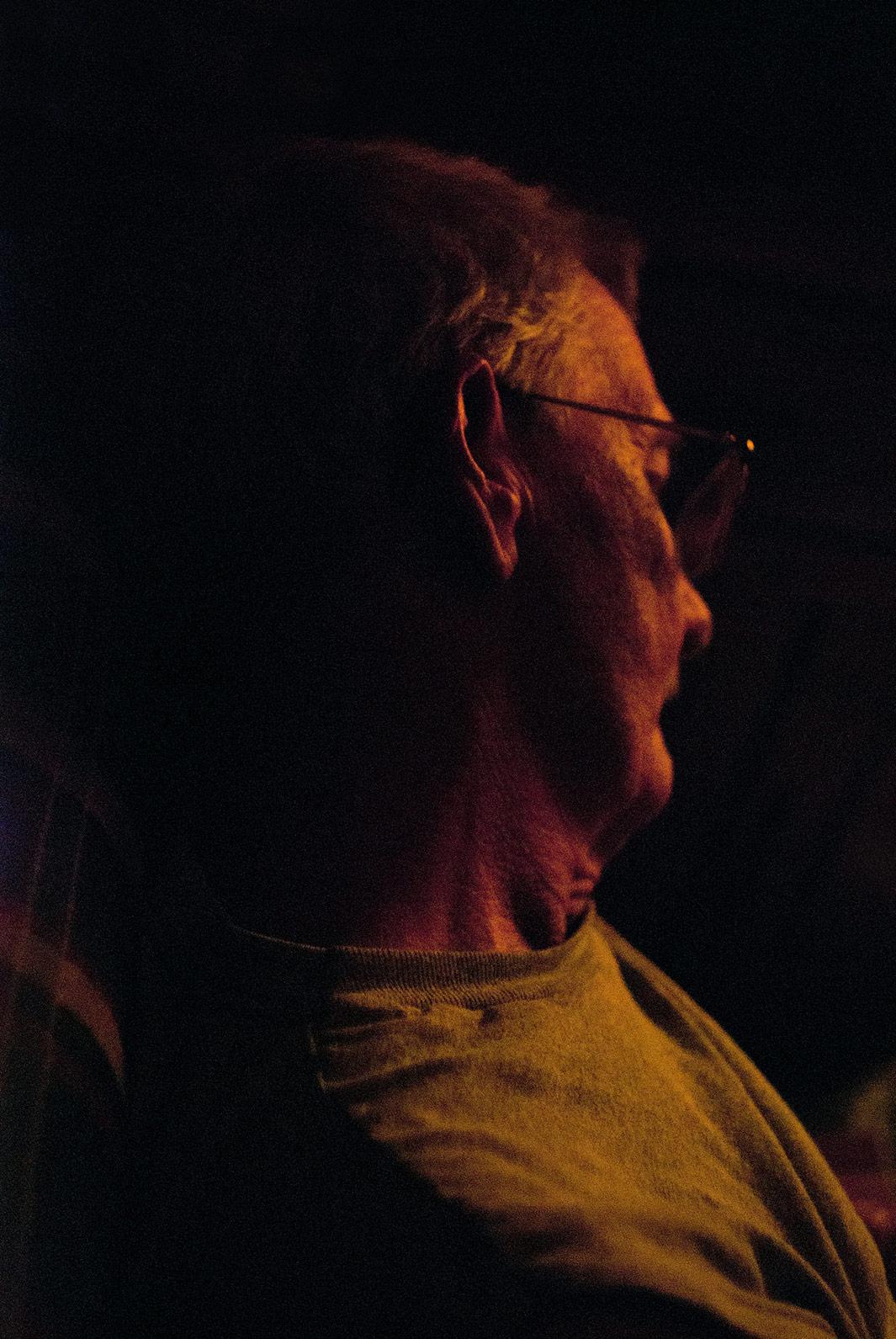

When he took the photograph while his father was sleeping as an adult, Ellenberg made the shot with a point-and-shoot camera that was developed in oversaturated color. “The warm hue of that image is meant to convey affection and fear,” he said. “If the black-and-white images elude to a memory, then perhaps color evokes urgency, as if it is happening even now as we see it in print. Alternating between the two, as well as between photographic formats, I’m attempting to blur the lines of what I recall, what I admit to, and perhaps what I want to see.”

Many of the images in the series were taken with a large-format camera Ellenberg used in tandem with the stark quality of a monochromatic print. Together, those mediums highlight the quiet nature of his family’s relationship. Ellenberg said most of the images were made in 2010, and apart from showing the work to some friends and colleagues, he decided to keep the project private for a while. “It was important that I understand my intention for the project and furthermore why I would ever want to show it publicly,” he said.

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

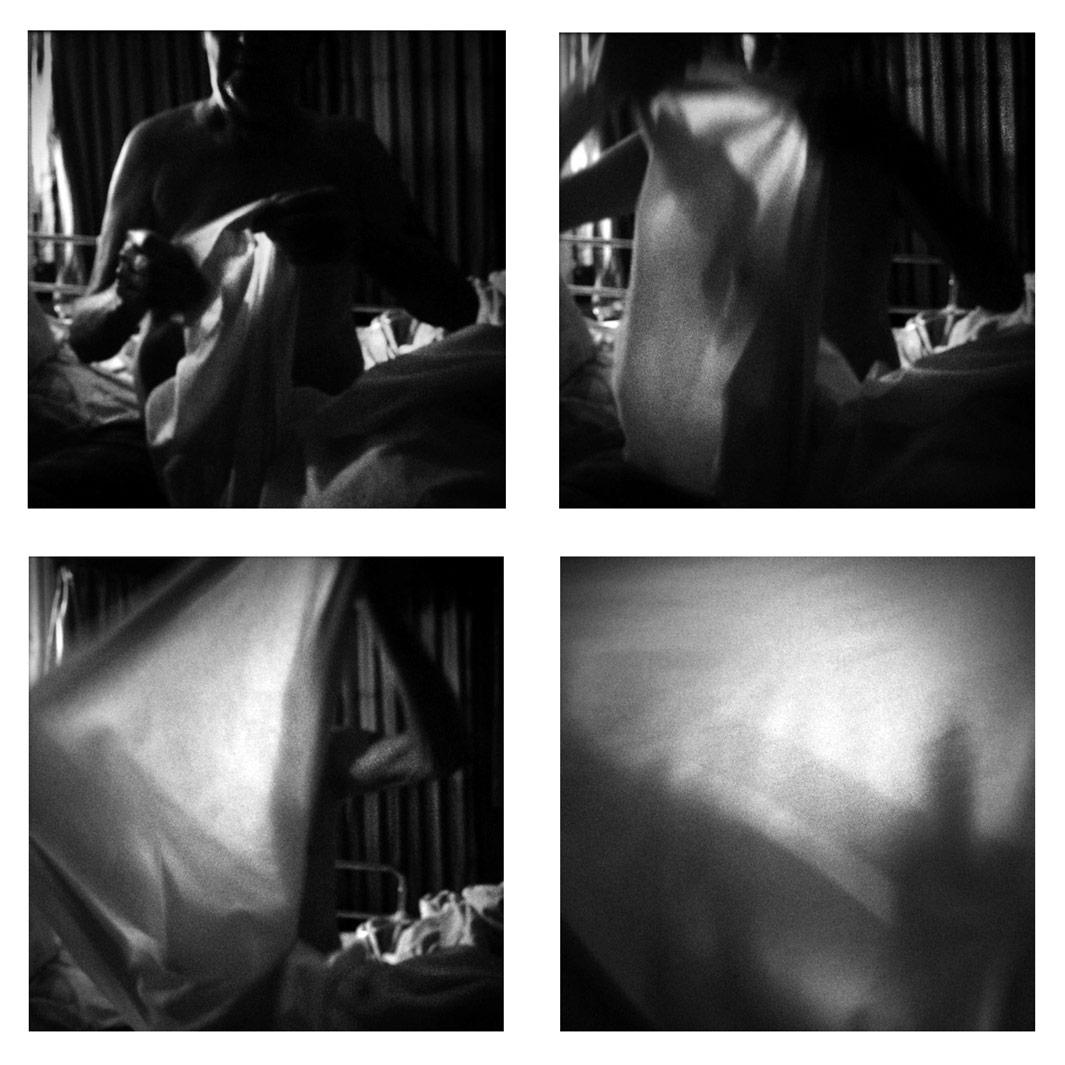

But in July, Ellenberg’s father was diagnosed with cancer that had spread to his bones. His father declined treatment, choosing instead to stay at home with his family during his final days. While dealing with his own grief, Ellenberg wanted to also document the experience in the least obtrusive manner, so he choose an iPhone as his means of recording the events. “It was important that I not only respect the grieving space of my family, but also that I allow myself room to be as present as possible,” Ellenberg said.

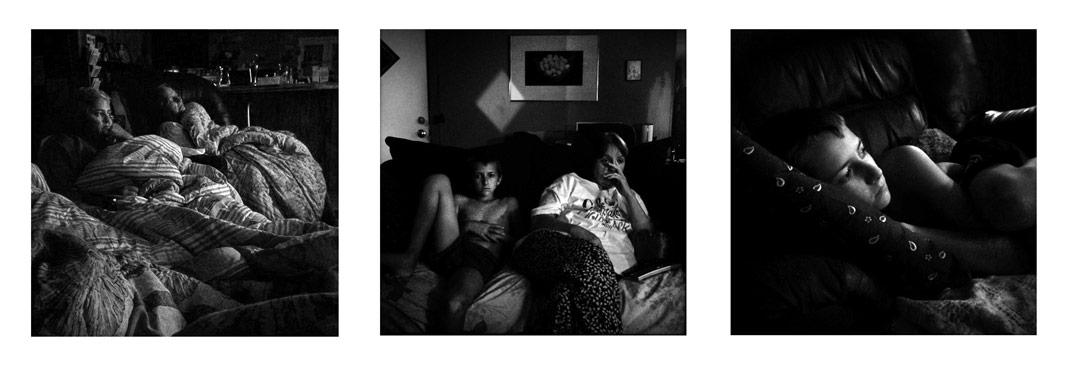

Ellenberg sees the work as something that shows the quiet side of his family as well as their affection for one another. “If the earlier portraits were a stark depiction of our reserved kinship, then perhaps the passing of my father shows us challenging our capability of affection,” he said. “What began as an investigation into the inner workings of my father had expanded into an exchange with my family. By the time I could vocally express to my father what he meant to me, he was unable to respond. The questions of ‘why’ still remain—perhaps through sharing these image I can arrive at a better understanding.”

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg

Eugene Ellenberg