In the fall and spring, Oregon’s Cascade Range is inundated with independent entrepreneurs on the hunt for wild mushrooms. The commercial hunters set up camp, stay for a few months, and then go on their way. Photographer Eirik Johnson grew up picking mushrooms with his family but had never seen the camps where other hunters lived. “We weren’t as serious about it. We’d go for a couple hours and then have a burger and a shake afterward and then have meals for the rest of the week of the mushrooms we picked,” Johnson said.

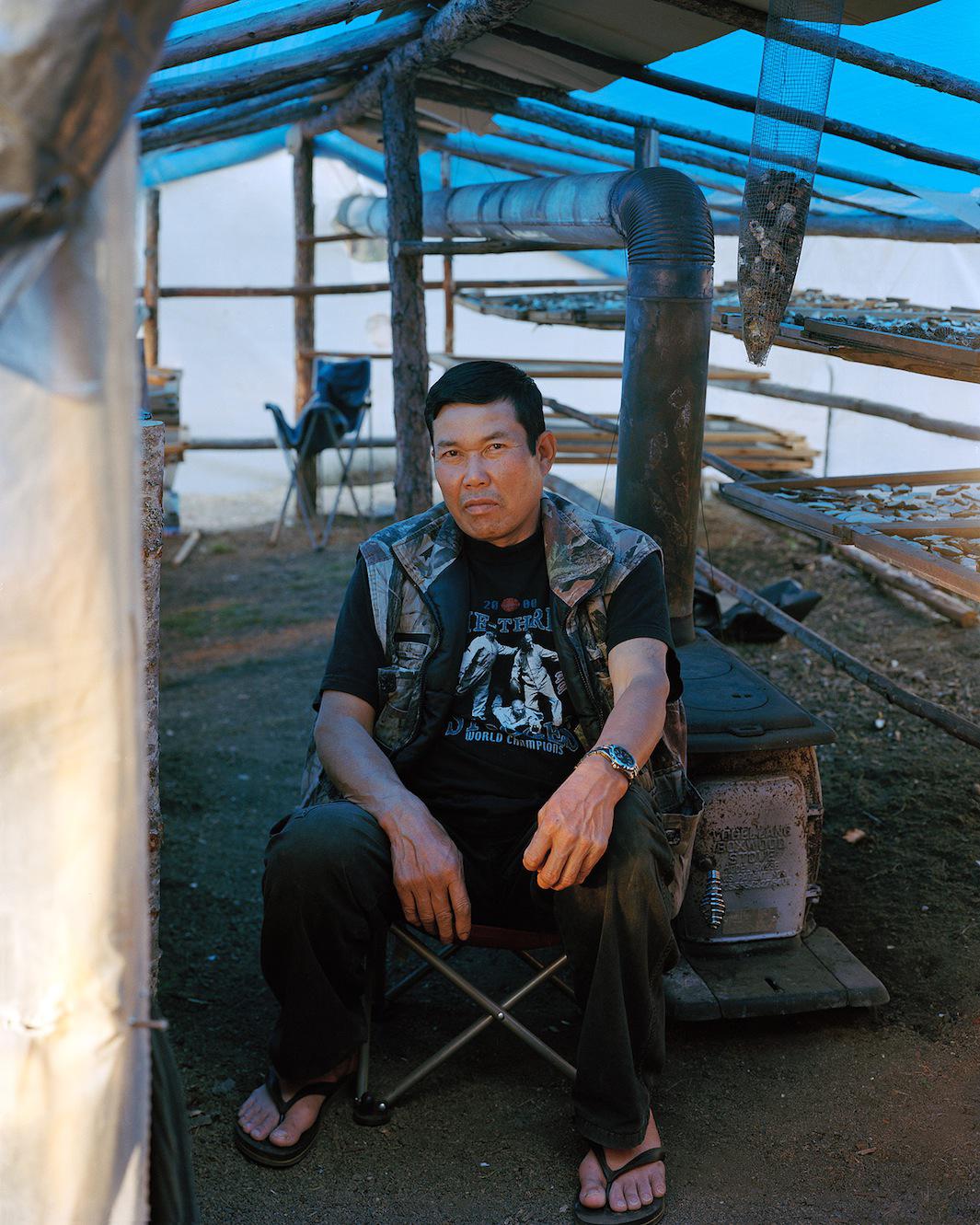

On a hunch one season, he decided to go investigate. What he discovered, which can now be seen in his series “The Mushroom Camps,” was a thriving community of pickers, a mix of Southeast Asian families, Mexican migrant workers, and old timers from local communities. What they had in common, Johnson said, was an independent spirit. “They have this shared libertarian desire to be out there and off the grid. Their mentality is that nothing’s better than being on your own, going out, and making a living based on what you pick,” Johnson said.

Johnson visited the camps for several seasons, often camping alongside his newfound friends and going with them on mushroom hunts. The most serious hunters, Johnson discovered, spend all day hunting, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., and can come away with a haul of hundreds of mushrooms. Some spend the whole year hunting, traveling to different locations where the mushrooms are in season. “It can seem tough if you’re not used to it, but I think they really like it,” Johnson said. “If you don’t want to pick one day, you can go fishing, play horseshoes, maybe over a weekend head to town to say hello to your kids. It is sort of this extended getaway in a sense.”

Eirik Johnson

Eirik Johnson

But while mushroom hunting is a hobby and a pastime for some, it can come with high financial rewards. Depending on the demand, Johnson said matsutake mushrooms could go for upward of $60 per pound and are used in high-end restaurants around the world. “It used to be that people could get into serious arguments. There was occasionally a gun drawn,” Johnson said. “It had in the past more of a Wild West frontier aspect to it. Things have calmed down as it’s gotten more regulated.”

In addition to the various personalities at the mushroom camps, Johnson was also interested in photographing the temporary structures the hunters construct for their seasonal shelter. Built out of tree branches, plastic tarps, and other found materials, the shacks are often abandoned after the end of the season, a phenomenon that proved visually rich for Johnson. “Their connection to the place interests me and the fact that they spring up like mushrooms for the season and then disappear. They take their plastic tarps down, and the sort of skeletal remains of the shacks remain, but it feels like a strange ghost town,” Johnson said.

Eirik Johnson

Eirik Johnson

Eirik Johnson

Eirik Johnson

Eirik Johnson