In 2012, Preston Gannaway was living in Norfolk, Va., looking for a coming-out story to cover for the Virginian-Pilot, where she was a staff photographer. Gannaway met Tavaris “Teddy Ebony” Edwards, a 21-year-old gay man living in public housing in Chesapeake, Va., who came out when he was 16. Because Edwards represented several demographics rarely covered in the paper—gay, black, poor—Gannaway decided instead to focus on Edwards and his experience living in Virginia.

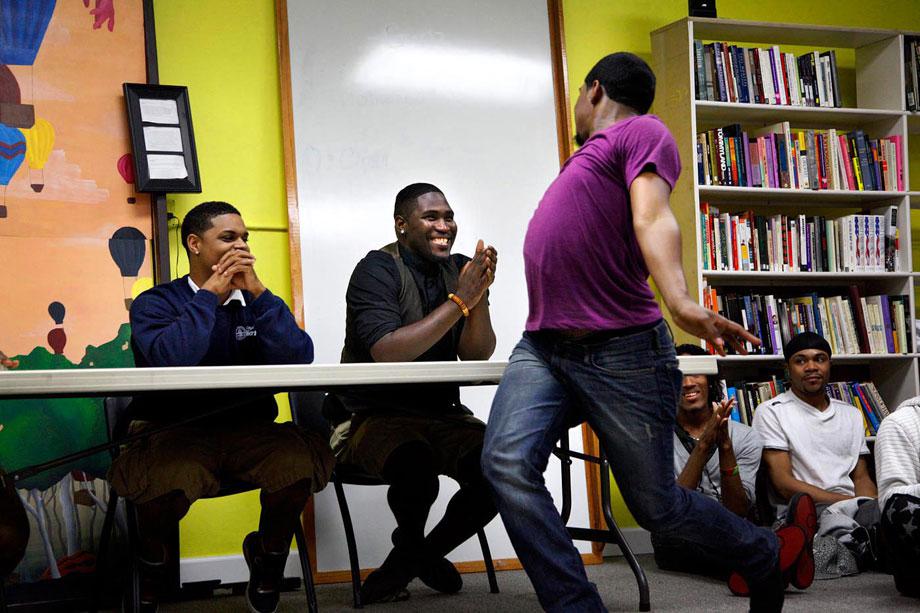

Gannaway ended up spending a year photographing Edwards while he was studying at Norfolk State University and Tidewater Community College. She documented him while he participated as a Spartan Guard in the Spartan Legion Marching Band at Norfolk State, as well as his involvement in the ballroom scene.

Throughout the project, she was pleasantly surprised not to see too much prejudice surrounding Edwards’ sexuality. “If someone is just keeping his head above water, struggling to keep the lights on and food in the fridge, he’s not going to be worrying about who some other guy is sleeping with,” Gannaway noted about living in a financially struggling community. “Family and community [are] very important. That seems to trump just about everything.”

Preston Gannaway

Preston Gannaway

Preston Gannaway

That isn’t to say Gannaway didn’t face other issues while working with a 21-year-old. “My friends would joke that I was in an abusive relationship with him because I was constantly waiting around for his calls or planning my weekend around his activities,” Gannaway said. (She likes to plan; Edwards doesn’t.) “I had to accept that [Edwards doesn’t like to plan] and learn to get into what I call the Zen of Teddy. It’s important that he live his life as he normally does, even if was often frustrating to me as a photographer.”

Gannaway had the additional challenge of going into Edwards’ community as an outsider, a white woman. “Around his neighborhood, there was some initial distrust. And with good reason: White people usually don’t come into Teddy’s housing complex for positive reasons. He often had to tell people I wasn’t a cop,” Gannaway said.

Preston Gannaway

Preston Gannaway

Preston Gannaway

The day before Edwards’ story was supposed to run, the Virginian-Pilot killed the story, which devastated both Gannaway and Edwards. “It was probably more of a shock to me than it was to him. Teddy is poor, black, and gay. He’s been marginalized in ways I’ll never understand.”

Time’s LightBox ended up publishing the images, along with Edwards’ story in his own words. Edwards received positive feedback from around the country, but Gannaway said she “got the impression that it wasn’t the same as if his hometown paper had run it. … [It’s] sad to me that this vibrant black gay community is still pretty much invisible to the Hampton Roads white community, and that they didn’t get to know Teddy through the story.”

Gannaway was recently a finalist in Photolucida’s Critical Mass 2013 photo contest. Her Kickstarter campaign to fund the book on her project, “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea” about a working-class community near Edwards’ hometown ends on Nov. 12.

Preston Gannaway

Preston Gannaway

Preston Gannaway