Warning: This post contains nudity and graphic imagery.

Ji Yeo

Pulled faces and enlarged breasts have become ubiquitous to the point of seeming almost normal in a pro-plastic surgery culture. And yet there is still an unwillingness to admit to having “work done” by a large percentage of people who reinvent themselves.

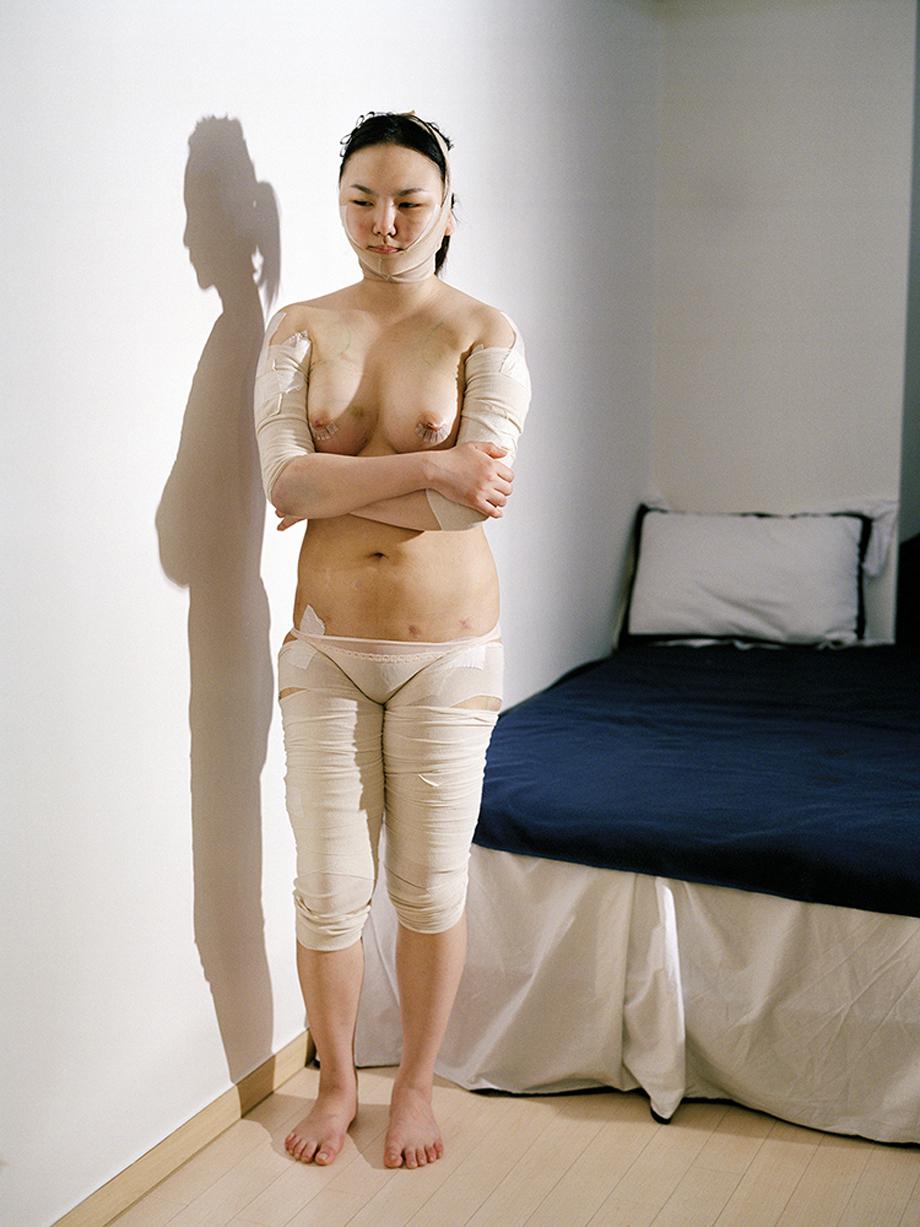

Photographer Ji Yeo managed to track down women who went under the knife and who were willing to sit for her series of portraits titled “Beauty Recovery Room.” Even more remarkable, Yeo isn’t interested in photographing the women in their new, enhanced state but rather immediately after their procedures, capturing the gory site of the women during recovery.

“The idea of recording the moment when they look their worst: showing their bloodstained bandages, bruises, surgical guideline marks, and swollen body is not part of the fantasy of transformation,” Yeo wrote via email.

In order to convince the women to work with her, Yeo found subjects who didn’t have support from friends or family and made a deal with them: She would take care of them during the isolating, painful, and sometimes shameful period of transformation. In return, they would sit for a portrait. Yeo would drive them to surgery, pick them up and take them home, cook soup for them, and pick up drugs from the pharmacy for them; she was both a servant and a confidant.

Ji Yeo

Although she was surprised how devoid of fear many of the women were about going under the knife, she was equally shocked to see how pleased they were immediately after the surgeries. “During the photo shoots, even though they were in extreme pain, I could feel their excitement, the excitement of hopes realized,” she said. “They seemed not to have the fears that I had; in fact, most of them were planning other surgeries in the near future.”

For “Beauty Recovery Room” Yeo concentrated on women in South Korea, though she studied at the International Center of Photography in New York and now lives in the United States. She noticed that in Korea most women focused on their faces as opposed to American women who seem to work on their bodies as well. The women in Korea were looking to create bigger and wider eyes in an attempt to appear more like Caucasian women while also keeping a childlike appearance that in Korea is tied to both femininity and innocence. “This difference illuminates the fact that women across cultures are altering their form in various ways to respond to a patriarchal media that perpetuates specific but distinct ideas of what a woman should be,” she wrote.

That idea is a driving force behind Yeo’s work, and she said “Beauty Recovery Room” is a way for her to “address my own aching questions about beauty and the pursuit of it, in its new and technologically altered form.” Yeo feels her portraits confront the viewer with a mix of judgment and empathy; she feels what she is photographing shouldn’t exist but knows it won’t disappear. “Our desire to be loved and valued coupled with our insecurity is far too powerful and far too well-fed to expect a dramatic rebellion … my images are simply a societal and sociological record of a widespread transformation about the lengths we are prepared to go to in order to attain an idea; they are an affirmation, a question, an argument, and a challenge,” she said.

Ji Yeo

Ji Yeo

Ji Yeo

Ji Yeo

Ji Yeo