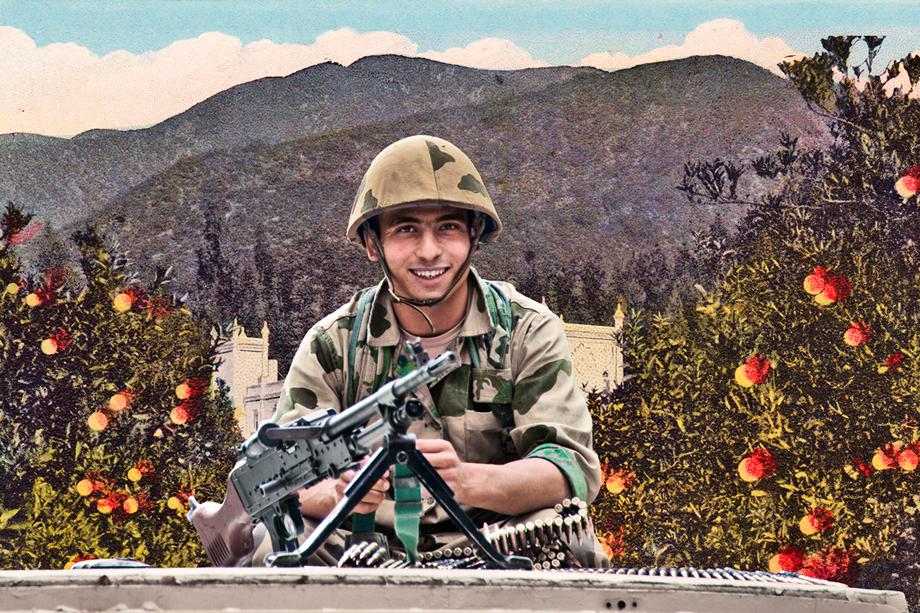

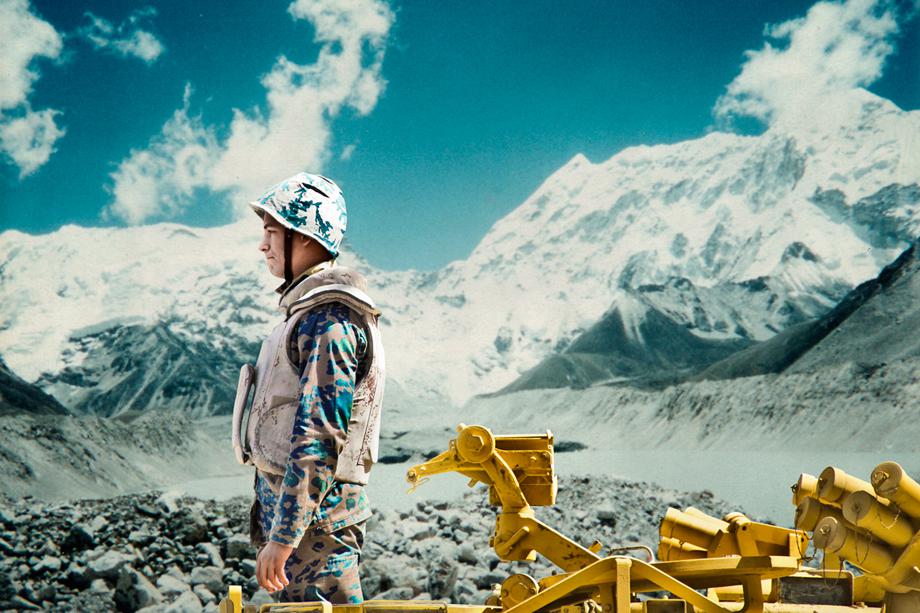

Artist Nermine Hammam was in Tahrir Square during Egypt’s revolution in early 2011 waiting to take pictures of the arrival of the Egyptian army.

She describes the waiting period for the army to arrive as almost mythological: the idea of a powerful, masculine force, a “military might” that would arrive almost “from outer space” to settle the situation.

But instead, at the location where Abercrombie & Kent buses had recently transported tourists to the famous square, hatches opened up from the tanks to reveal a completely different type of soldier. “I started looking at these boys who are 16, 17, or 18 and had never been to a city,” Hamman said about the young soldiers.

Or, as she wrote in her artist statement: “I couldn’t help but notice their youth. Their wide-eyes and tiny frames were so different from the police forces we had grown familiar with. They were the sons of anxious parents. They stood on street corners, squinting at the cacophony of Cairo, observers of history, not the angry stereotypes of masculinity through which our narratives of the army are articulated.

Nermine Hammam

Nermine Hammam

Nermine Hammam

She began taking pictures of the young men and blended them with postcards to create images for a series she titled “Upekkha.” The title refers to the Buddhist concept of equanimity, which is a common theme in her photographic projects.

Hammam was born in Egypt, went to boarding school in England, and studied film at New York Univerity. “I edit the images I think represent something. I think maybe the soldier’s innocence, the idea that we don’t really see the soldiers: They are covered, and you don’t come close and look at the people because we have dehumanized soldiers,” she explained. “For me it was ‘Who are these kids?’ I’m sure these kids would rather not be in Tahrir Square, not sleeping for days, not having toilets, not eating properly; they would probably rather be on holiday.”

For Hammam, herself a mother, she said looking at the soldiers made her want to transport them to pleasant places, to reassure them that they’d be OK. “This work is about youth, universal youth, and the harshness and inhumanity of sending our children to war,” Hammam said.

Nermine Hammam

Nermine Hammam

Nermine Hammam